Quisiera cantar bonita, softly sang the curly haired light-skinned woman dressed in a t-shirt and capris as she entered from the back of the room. “I’d like to sing pretty.” Tied around her right ankle was a piece of rope with which she noisily dragged a small foot stool behind her on the ground. At the front of the room were three other women arguing about their singing and dancing abilities, in preparation for a “spectacle”.

Thus began the 30 minute original drama on domestic violence and its consequences performed by the theatre team of the feminist women’s collective 8 de marzo that I attended last week. Theatre is one of the many strategies the collective uses to raise awareness about issues facing women in Nicaragua, including domestic violence, sexual and reproductive rights, and active citizenship. 8 de Marzo has been working for over 15 years in the highly industrial, infrastructurally precarious, and environmentally contaminated eastern sector of the city. This summer I am getting to know the women of this collective and participating in their activities as the first stage of what I hope will become a long-term ethnographic project examining how women in marginalized communities overcome situations of interpersonal violence and assume activist or leadership roles in their neighborhoods. This is a question with ongoing relevance, give the escalating violence against women in the region over the last decade (Carey and Torres 2010; Wilding 2010; El Nuevo Diario 2011).

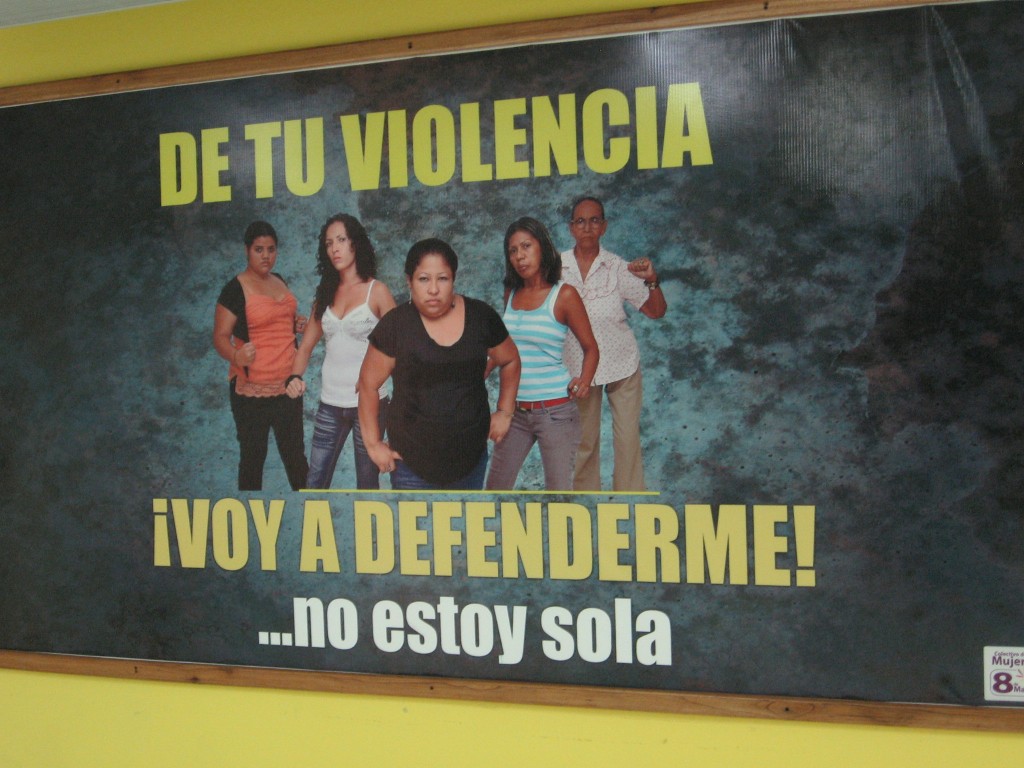

“I’m not going to put up with your violence. I am not alone.”

The question of women’s empowerment has gained prominence in recent years in response to the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals (MDG #3) and the rise of microenterprise and microcredit, both of which are frequently directed at women in developing countries. Although economic independence is widely acknowledged as a key component of women’s empowerment, my research is focused on other dimensions of these processes—particularly how local context, gender power relations, and class interact in the formation of women’s subjectivities and their modes of collective action.

The 8 de marzo collective has a small office on the east side of the city, where I’ve spent most of my time for the last week or so. Their house simultaneously serves as a meeting place, a haven for help and resources, a training space, and a place to share tortillas, queso, and frijoles amidst lively banter around a crowded counter top at lunchtime. I feel honored that I’ve been offered a seat at this counter amongst women who have been struggling so long on behalf of themselves and their compañeras. I’ll never forget the day we met—after I introduced myself, two women turned to each other and said wistfully “can you imagine…a doctorate!” Embarrassed, I quickly replied that titles mean very little and their knowledge and experience is already quite vast.

I’m the one who still has much to learn.

Carey Jr., David and M. Gabriela Torres. 2010. “Precursors to Femicide.” Latin American Research Review 45, 3: 142-164.

El Nuevo Diario. “ONG: 90% de las mujeres en América Latina han sufrido violencia.” 18 June 2011. Web.

Wilding, Polly. 2010. “‘New Violence’: Silencing Women’s Experiences in the Favelas of Brazil.” Journal of Latin American Studies 42, 4: 719-747.