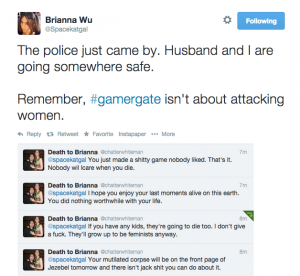

SXSW, #GamerGate and Gendered Boundary Policing

@SXSW first fracas covered by Katie Rogers

Rock Climbing Culture in Austin, TX

by Corey McZeal

This post consists of excerpts from Corey McZeal‘s M.A. Thesis entitled, “Rock Climbing Culture in Austin, TX.”

Supervising Committee: Dr. Harel Shapira and Dr. Sheldon Ekland-Olson.

The sport of rock climbing has seen a boom over the last two decades. Interestingly, this boom has not been due to the extreme commercialization of the sport, but by the increasing availability of indoor climbing venues that allow individuals to foster the skills that allow them to eventually climb outdoors. While the demographics of climbers can vary by region, in Austin, Texas climbers tend to be middle class, male, and white. Through my research on the climbing culture in Austin I seek to discover what features of the sport make it so appealing to this particular demographic. Through ethnographic methods, in-depth interviews, and participant observation, I gained insight on the climbers’ motivations. Additionally, though climbing offers a peculiar mixture of pain, injury, and even the potential for serious injury, climbers see it as a “stress reliever.” Throughout this thesis, I seek to discover how climbers manage this apparent contradiction, and what their participation in the sport can tell us about other aspects of their social existence. Full post

Food for Thought

On February 8, The University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies hosted a symposium entitled, “Food for Thought: Culture and Cuisine in Russia and Eastern Europe, 1800-present.” And, like a dessert of chocolate cake with chocolate icing, served alongside a scoop of chocolate ice cream and a mocha latte, the subject matter was hyper-specific and singularly oriented, but rich and filling in its handling of food and cultural development.

Viewing cultural developments through the lens of food offers profound insight to both historical and sociological phenomena. A common thread tying together many of the talks was food production and the nationalization of food – the tendency for food to be a reflection of a nation or culture and also a process contributing to a nation’s identity. This reframing of food demonstrates the import that specific products, and their production, have on a nation’s cultural identity.

As one who is generally naïve and uninformed regarding Russian, East European, and Eurasian studies, the talks were surprisingly engaging because one did not need to be a scholar in the field to follow along. Three talks, in terms of their digestibility to “outsiders,” stood out: Adrianne Jacobs’ “A Hunger for the Past: Gastronomic Historicism in Brezhnev’s Russia and Beyond;” Robert Rothstein’s “Salvaging Culinary Ethnography: A Path to Belarusian National Identity;” and Jordan Kuck’s “Consuming the Leader: Agriculture and Food as Sources of Political Legitimacy and Historical Memory.”

Jacobs’ talk was engrossing because he neatly tracked culinary trends in a way that made it easy to follow along. Through an analysis of 1960s and 1970s state-led programs and restaurant practices, Jacobs noted how Russian culinary trends “evolved as a need to embrace, simultaneously, tradition and innovation.” This led to curious epicurean endeavors, like a short-lived infatuation with whale sausage; the whale being the “innovation” and the sausage being the “tradition.” Jacobs extends this analysis to make cunning arguments about the shifting nature of Russian policy and the ambiguous embrace of traditional Russian nationalism.

Rothstein explored Belarusian national identity through its cuisine. As a newly independent country (relatively so), the idea of what it means to be Belarusian is difficult to articulate and, according to Rothstein, one way it is expressed is through food. Still, this is a complicated expression, as Belarus is a diverse country with sizable populations of Muslims, Christians, and individuals born in other Soviet states. Like many former Soviet states, Belarus’ national identity is constantly formed and reformed as it works through creating an identity out of the hodgepodge of other cultural influences. In terms of food, these influences are both national; Polish food, for instance, is featured prominently in what is increasingly termed ‘Belarusian’ cuisines – as well as religious influences. In this way, food traditions offer scholars a clever rhetorical device to reflect the more general, and challenging, process of forging a cohesive national identity.

Kuck’s talk provided an example of how food history can become intertwined in an important, and occasionally comical, way in nation building. The democratically elected, but ultimate dictator of Latvia, Karlis Ulmanis, spent significant state resources throughout the 1940s and 1950s to cultivate the previously non-existent Latvian dairy industry. Throughout this time, according to Kuck, dairy products became an important element of Latvian national pride – so much so, that Ulmanis is memorialized through statues made of margarine and depicted in artwork with sticks of butter in his hands.

But, just as the most frustrating and difficult part of most meals is the mess it produces, and the inevitable need for a cleanup, making generalizations about food, its meanings, and its broader reflections of national culture is a messy and complicated argument that requires delicate scholarly care. Food consumption and production, by its very nature, is an involved, idiosyncratic, and individual experience. Families and individuals experience the same titled food in dramatically different ways. While there is Jewish food or Latvian food or Bulgarian food, as presenter Justya Straczuk noted, it’s outrageous to suggest that there is a universal way in which this food is prepared and experienced. At times, it felt as though the conference was advocating this generalized experience of food, as opposed to exploring the subtleties of how divergent food traditions came to be or why they matter in a historic or sociological way. Lee Shai Weissback’s and Eve Jochnowitz’s talks, in particular, felt guilty of this tendency: both discussed Jewish food without offering the necessary caveats of 1) what this means and 2) how this experience is inherently individualized and experienced differently by different people and in different contexts.

These discussions offer a cautionary tale for sociologists hoping to analyze the import of food to culture and society. Yes, it is an entertaining and rich field and, given the turnout for the event even with poor (by Austin standards) weather, one that will attract a crowd. But, there is a risk to placing such an emphasis on one component of an individuals’ life because it can lead to sloppy scholarship, generally, and the overstating of how one’s experience with food is emblematic of broader trends, specifically.

Ultimately, the symposium’s title, if somewhat banal, was apt: it provided its audience with plenty of food for thought. Exploring and analyzing the traditions of food and their import to an area’s history and contemporary culture requires a lot to chew. Some masticated better than others, but on the whole this symposium succeeded in analyzing an often overlooked area of food scholarship.

Finding the Time to Make the Wine

My journey as a graduate student is officially underway. I have spent the past few months of my life navigating the ins and outs of life as a Longhorn. And while I haven’t been entirely overwhelmed yet, I have met my fair share of first semester obstacles. After all, I’m a TA for the first time, I’m trying to make sense of Marx, Weber and Durkheim, I’m computing two-way ANOVAs by hand, I’m learning to be one with the Large SOC Printer, I’m finding out that there is free coffee in the break room, and really, I’m just trying to not step on anyone’s toes.

Seriously, though, as a first year graduate student I will say that I have been delighted by the show of support from the department as a whole. Faculty, staff and students have been clear in their support for a work-life balance. I’m on board, and I think this message is vital to our success as individuals, as colleagues, as cohort members and as research collaborators. We have to stay sane through the stages of thesis, comps, dissertation, publications… wait, just breathe. It is week 9 of my first year. I am confident that I will get to all of those things in due time, but I’m not there yet. I’m not ready yet. And, frankly, I think that is okay – it has to be okay!

In order to be successful at the graduate level, you’ve got to put in a lot of work before you can enjoy(?) the fruits of your labor. There is a lot of preparation involved, and then there is the necessary patience. Quick, what is your research question? What are your methods? Do you even have data that can help you? Figuring out the nuts and bolts is essential, and then there is IRB. So yeah, you have to plan before you propose. Furthermore, you’ve got to be okay with rejection – revision, at least. Surely, I wouldn’t want to get used to rejection, but you have to accept it as part of the peer review process. Then in the end, everybody wants to know two things: Is your study valid and can it be replicated?

I would like to take this opportunity to share my balancing approach. For the past couple of years, I have been passionately involved in making my own wine. In a lot of ways, being a graduate student is like being a vintner. Really, there are just so many parallels. The more I think about it, the more I see that in order to make a fine wine, you’ve got to plan, prepare and look for inspiration. How is that not like conducting social science research? For instance, winemakers keep detailed notes about their recipes. Without a written log, the wine cannot be replicated or even tweaked for future attempts. Researchers, ring a bell? Winemakers, like published academics, also need to have patience through the process. Those of us who make wine understand that you can’t drink the solution right away. Similarly, most researchers can’t publish without a few rounds of revisions.

I would like to take this opportunity to share my balancing approach. For the past couple of years, I have been passionately involved in making my own wine. In a lot of ways, being a graduate student is like being a vintner. Really, there are just so many parallels. The more I think about it, the more I see that in order to make a fine wine, you’ve got to plan, prepare and look for inspiration. How is that not like conducting social science research? For instance, winemakers keep detailed notes about their recipes. Without a written log, the wine cannot be replicated or even tweaked for future attempts. Researchers, ring a bell? Winemakers, like published academics, also need to have patience through the process. Those of us who make wine understand that you can’t drink the solution right away. Similarly, most researchers can’t publish without a few rounds of revisions.

Did you know, roughly 90% of the wine making process comes via the proper sterilization of your materials? Again, you have to be prepared or else you run the risk of contaminating your solution with bacteria. If that happens, your wine will turn to vinegar. Then, even if you’ve properly cleaned all your bottles and you’re sure you’ve added the yeast at the correct temperature, all you can do is wait. The yeast will die only after they’ve eaten all the sugar and burped it into alcohol. And still, you wait. You have to let the yeast settle down to the bottom of the cloudy mess they burped up. Then, around six weeks in, you get to taste the wine for the first time. Your lips touch the solution as you siphon of the bounty from the dredges. At this stage, it is a treat for the steady soul. Unrefined and at room temperature, tasting a country wine fresh off its fermentation is like reading your first set of peer reviews. It hurts, but it is so good. And so you “rack”, or siphon, a few more times until the solution is crystal clear and finally, 10 months later, you’ve produced a valid and tasty wine. Maybe you craft fancy labels and affix them to the bottles. In the end, when the crate of bottles is empty and you have made your toasts to friends and family, you’ll want to replicate that solution again.

I am so far from mass production on a quality level, both in terms of wine and research. But you have to start somewhere right? If you want to read about the boring details of my ah-ha! research moment, ask to see a copy of the statement of purpose that I submitted to UT this time last year. I’ll spare those details here. As for my aspirations to become a vintner, I found my inspiration in December of 2010. For Christmas, my mother gave me a book titled, “First Steps in Winemaking”, written by a British fellow named CJJ Berry. How do I know he’s British other than the blurb on the back cover? He uses instant coffee (Nescafe) in his recipe for Coffee wine on page 135. And while the Coffee wine was deplorable (I poured my failed attempt down the drain), the Nescafe is the real joke! Seriously, who drinks that?! As I digress, let me not burn any trans-Atlantic bridges with my first blog post!

Along with the book, “First Steps in Winemaking”, my mother gave me four quarts of honey and suggested that I ferment the honey into Mead. Every year, my parents harvest honey from their 12 beehives, but they have never tried to ferment it into Mead for themselves. In giving me the book and key ingredient, they knew they were going to get a taste on the back end. What a gift! Anyway, if you want to check out my parents’ website, please feel free to visit them at www.straightcreekvalleyfarm.com/. Also, be sure to check out the link at the bottom of the page! It is nothing more than a shameless plug for my mother’s own blog, where she writes about being a retired lawyer and living off the grid. In that particular post from earlier this fall, she documents the honey harvest. Anyway, I made the Mead and it was fantastic! Ever since, I’ve been hooked on trying new recipes and making various country wines.

When I say I make wine, I’m not talking about grape wine. You’ve probably gathered this by now with my mentions of Coffee wine and Mead. Neither my mom nor I have ever made wine from grapes. In her footsteps, I’ve only fermented various fruits and flowers. These are called country wines. From CJJ Berry: “One of the exciting things about making country wines is that you can use the wide range of ingredients you have at your disposal to make wines of a vast variety of flavours. Better still, many of these ingredients are free! There are five main sources: fruit, flowers, vegetables, grain and leaf or shoot (which includes herbs).” (114). When I was younger, I remember my mom making her first batch of Watermelon wine. The one thing that sticks out in my memory is the overpowering smell of the yeast. Now that I’m used to it, I use it as an indicator because I know I’m on the right track when I smell the yeast burping into the wine solution!

Since the Watermelon wine, my mother has produced Dandelion wine, Paw Paw wine, Apple wine, Marigold wine and Blackberry wine. After I made the Mead, I had the failed attempt at Coffee wine, followed by a successful Green Anjou Pear wine and a Grapefruit wine. My latest creation is a Pineapple wine, which was inspired by a 2012 trip to Hawaii for the Law and Society Association’s annual conference. I thought how sweet a Pineapple wine would taste while sitting on the beach at Hanauma Bay in Honolulu. Now, over a year later, I’m at the point in the process where I have bottled the Pineapple wine. I’ll let it rest through the Winter, but it should be ready by March 2014.

I try to incorporate new and exciting activities into the daily routine of being a graduate student. Next time you go to a conference in a far off city, try to find inspiration outside the walls of the hotel. Now that I am in Texas, I have been asking folks about the native fruits and flowers of the Hill Country. From what I’ve heard about the area’s agriculture, I’m thinking I’ll ferment some local peaches next time around! Or maybe some mint! I don’t mean to saturate the work-life balance forum – my goal here is to enhance it. What are some of the things you like to do to balance out your days?

Social Logical Lens on the Canopy Art Studio – Austin and the Artist’s dilemma

Moto GP at Austin’s Circuit of the Americas by Caity Collins

Moto GP, or the Road Racing World Championship Grand Prix, was held in Austin for the first time at the new Circuit of the Americas (COTA) motor racing circuit last April. This was my first time to a motorcycle race, so I wasn’t sure what to expect or whether I’d enjoy it (machismo and motor sports not being two of my passions). But I attended openminded with a couple of die-hard motorcycle enthusiasts who can talk all day about the riders, their histories, and the mechanics of the bikes, which made the experience a lot more fun. I’m happy to report that I’m already looking forward to next year’s races (more passion for the motor sports now, still none for the machismo).

A little history about the track: COTA hosted the Formula One US Grand Prix in November 2012. The facility is meant to hold roughly 110,000 spectators around the periphery of the 3.4 mile long track. COTA is built on 890 acres of undeveloped land in southeast Austin, which was originally slated to become a residential subdivision. Its largest investor is Red McCombs, a Texas billionaire for whom UT’s football stadium is also named. The facilities also have an ampitheatre for concerts, which is quickly becoming a popular hotspot for big bands passing through town.

And now, a little info about the races: the races are split into three divisions: Moto3, where riders race 250 cc bikes, Moto2, where riders race 600cc bikes, and MotoGP, where riders race 1000cc bikes. Most races last 40-45 minutes, with roughly 20 riders covering a set number of laps. Top speeds during MotoGP are an earsplitting, incredible 210 mph. If you sit on the grassy hills overlooking the track, you watch them zoom by at breakneed speeds, and then wait a minute or two until the pass by again. If you sit in the grandstands or hang around the paddocks and main area of the track, there are large screens on which you can watch coverage of every turn, as cameras and helicopters follow the riders. For a taste of the speed and riding from the racers’ perspectives, take a look at this onboard video.

We arrived when riders were still warming up, and you could hear the bikes from miles away as we approached COTA with our car’s windows rolled down – a high-pitched whining noise that made my friends giddy. As we settled into our camping chairs on Turn 7, I was stunned at the speed and the obvious talent and athleticism of the riders, and it wasn’t even race time yet. It felt like watching a video game – I got caught up in the crowd’s excitement, seeing riders fly by impossibly fast, dangling off the side of their bike with their heads impossibly close to the ground. Riders’ race suits are outfitted with an  airbag system that inflates automatically upon impact, and also relays the forces and location of the impact instantly to physicians who are standing by, should an accident occur during the race (which happened several times over the course of the day). On every turn, riders’ knees skid along the ground as they sweep around winding curves, and aggressive riders also put their elbows down. This year, many in the crowd cheered for Ben Spies, a rider from Dallas on this year’s circuit. We stayed all day to watch all three races, and I’ll admit I was fascinated for all 8 hours of them. Watching the dynamics of the riders as they try to cut each other off and pass one another is a lot like watching cyclists in the Tour de France, except these motorcycles accelerate as fast as an F18 fighter jet, and share the same aerodynamic physics as these jets, making things both a lot more dangerous and a lot more exhilarating in some ways. In the end, the Spanish swept the podium in Austin, both in Moto2 and MotoGP. For anyone interested in impressive athletics and breakneck speed, MotoGP is a sight to behold.

airbag system that inflates automatically upon impact, and also relays the forces and location of the impact instantly to physicians who are standing by, should an accident occur during the race (which happened several times over the course of the day). On every turn, riders’ knees skid along the ground as they sweep around winding curves, and aggressive riders also put their elbows down. This year, many in the crowd cheered for Ben Spies, a rider from Dallas on this year’s circuit. We stayed all day to watch all three races, and I’ll admit I was fascinated for all 8 hours of them. Watching the dynamics of the riders as they try to cut each other off and pass one another is a lot like watching cyclists in the Tour de France, except these motorcycles accelerate as fast as an F18 fighter jet, and share the same aerodynamic physics as these jets, making things both a lot more dangerous and a lot more exhilarating in some ways. In the end, the Spanish swept the podium in Austin, both in Moto2 and MotoGP. For anyone interested in impressive athletics and breakneck speed, MotoGP is a sight to behold.

A more sociological take on the races would be attentive to the raced, classed, and gendered dimensions of the weekend’s events. I’ll mention a few brief points here, the most obvious one being the elite nature of the sport (and many professional sports more broadly) – with regard to both participating and spectating. Sponsorship is required to ride – bikes cost roughly $3 million, and race suits and gear cost around $12,000. And with $30 parking and tickets starting at $40 a day, with the best seats going for over $1000, the  message is clear that the event intends to cater to the privileged only. MotoGP attracts a worldwide audience — here in Austin, the COTA track advertises that private airplanes can be chartered, arriving at private airports near the track. After an outcry from Austinites eager to visit races, COTA started a free shuttle service for Formula One, but not for Moto GP. “Umbrella girls” remain a central part of the MotoGP tradition — girls in scantily clad outfits hold umbrellas over the riders’ heads before the race starts. As with other motor sports, Moto GP is dominated by men, although one woman raced in the Moto3 category – Ana Carrasco from Spain. With the exception of one rider from Japan and another from Colombia, all riders were from the United States or Europe. Scholars of sport have covered the sociological dimensions of events such as MotoGP in a lot more detail than me – see Professor Ben Carrington’s research, and the work of Letisha Brown, Anima Adjepong, and Nick Szczech for other interesting takes on various sporting events.

message is clear that the event intends to cater to the privileged only. MotoGP attracts a worldwide audience — here in Austin, the COTA track advertises that private airplanes can be chartered, arriving at private airports near the track. After an outcry from Austinites eager to visit races, COTA started a free shuttle service for Formula One, but not for Moto GP. “Umbrella girls” remain a central part of the MotoGP tradition — girls in scantily clad outfits hold umbrellas over the riders’ heads before the race starts. As with other motor sports, Moto GP is dominated by men, although one woman raced in the Moto3 category – Ana Carrasco from Spain. With the exception of one rider from Japan and another from Colombia, all riders were from the United States or Europe. Scholars of sport have covered the sociological dimensions of events such as MotoGP in a lot more detail than me – see Professor Ben Carrington’s research, and the work of Letisha Brown, Anima Adjepong, and Nick Szczech for other interesting takes on various sporting events.

“Don’t Believe Me, Just Watch”: A Three-Day Adventure at SXSW 2013 by Shantel Buggs

This spring marked my second year attending the most eventful week on Earth also known as South by Southwest. South by Southwest (SXSW) is a 10-day long set of overlapping film, interactive and music festivals and conferences that takes place every spring in Austin, Texas, typically around UT’s Spring Break. Begun in 1987, SXSW Music is the largest music festival of its kind in the world, with thousands of official (and the occasional surprise) performers and bands playing in hundreds of venues all over downtown Austin. Collectively, SXSW is the highest revenue-producing event for the Austin economy, with an estimated economic impact of $167 million in 2011.

With musical acts ranging from Born Ruffians to Fitz and the Tantrums to Kendrick Lamar  to Justin Timberlake to Prince, SXSW 2013 had a little bit of something for everybody. However, if you’re planning on attending next year, you should know that it is a marathon and not a sprint. SXSW requires a lot of patience and endurance, as you will spend significant parts of the day waiting in lines, wading through massive crowds on 6th street and standing on your feet enjoying food and drink, for multiple days in a row.

to Justin Timberlake to Prince, SXSW 2013 had a little bit of something for everybody. However, if you’re planning on attending next year, you should know that it is a marathon and not a sprint. SXSW requires a lot of patience and endurance, as you will spend significant parts of the day waiting in lines, wading through massive crowds on 6th street and standing on your feet enjoying food and drink, for multiple days in a row.

DAY ONE: FADER Fort and The Woodies

The FADER Fort presented by Converse is one of the largest venues during SXSW,  sprawling over a couple of blocks between East 4th and 5th Streets. The wristbands for the Fort are some of the most coveted, with the RSVP window usually only lasting a few hours before the festival. This year, the site actually crashed before I could RSVP, so I had to depend on my out-of-town friend’s luck in procuring a guest wristband,

sprawling over a couple of blocks between East 4th and 5th Streets. The wristbands for the Fort are some of the most coveted, with the RSVP window usually only lasting a few hours before the festival. This year, the site actually crashed before I could RSVP, so I had to depend on my out-of-town friend’s luck in procuring a guest wristband,

After we received our wristbands on  Thursday, we went to stand in line.

Thursday, we went to stand in line.

Inside, the walls were covered in flyers and names or messages written in chalk, with TV screens showing the performers on the stage:

Leaving the Fort after Solange’ performance, we headed downtown:

Me and a few of my fellow Duke Alums randomly ended up at The Woodie Awards, to watch Macklemore x Ryan Lewis as the sun was going down:

DAY TWO: Downtown and VICEland

Until the line opened for the VICE party, we decided to spend most of the day at Toulouse, a bar on 6th Street known for its 32-oz Mason jar drinks. Because it was Friday – the second biggest day (in terms of attendance) of the entire festival – the streets were packed with people and street performers.

DAY THREE: Anti-Gay Protests, HGTV Love House, 6th Street and Food Trucks

After a lovely brunch at Moonshine Patio Bar & Grill, my friends and I again headed downtown. Even at twelve in the afternoon on a Saturday, the streets were busy. Saturday is the last and biggest day of SXSW, drawing the largest crowds of the 10-day stretch. Of course, what’s Spring Break without some religious protesting?

One of the best parts of SXSW is the FOOD. Austin is definitely known for its food truck scene and SXSW is the perfect opportunity to stuff your face while simultaneously getting exercise. On Saturday alone, I enjoyed jambalaya and beignets on a stick from Baton Creole, beef pho and filet mignon with garlic noodles from Get Pho Cup’d (located in the South by South Bites plaza) and pizza from Roppolo’s Pizzeria. There was a place that had duck tacos, but I was too full to try. I’m pretty sure I gained at least five pounds despite all of the walking I did.

While my friends and I had bigger plans for our Saturday, things changed when the party we’d intended to go to closed their line four hours before the show’s start (stupid lines!). Therefore, we ended up wandering around people watching the rest of the day. Although things didn’t go the way we’d planned, I had an amazing weekend, and I’m totally looking forward to next year!

Shantel G. Buggs is a 2nd year and food/music/pop culture junkie.

Sauntering SXSW Social Logical South Austin

What do transgender divas, a British invasion, biker havens and South Congress have in common? Sauntering Arts demystifies SXSW for Austin refugees.

It’s A Beautiful Day in Austin, Texas!

Here we have our nice, new building! The skybridge goes from the floor holding the Sociology department to the floor in the Student Activity Center holding the Anthropology department. Quite apropos. But the SAC has more than academic departments: some might argue the REAL treat of our new building is being next door to a Starbucks and Taco Cabana! If we were to turn around from here, walk a bit, and look back, we would see…

…The East Mall that goes right past our new building. Central to the East Mall and just outside the College of Liberal Arts building is the statue of Martin Luthor King that you see in the distance. While the graceful elder trees may suggest tranquility, the East Mall is a highway of humanity on any given school day. Of course, no look at the campus on a sunny day would be complete without….

The Tower that UT is famous for. The Tower sits square in the middle of campus with the four malls (North, South, East, West) all leading to the main building that the Tower is part of. While the Tower is a powerful – and infamous – symbol of UT, it also serves actual functions. For one, it IS a clock tower, and thus delivers powerful tolls every hour to let the so-late-for-class-no-time-to-look-at-phone student that they have missed the bell literally. Less well known is that the Tower lights up for special occasions. The entire structure is bathed in burnt orange lighting for sports victories, graduations, or the awarding of National Medals of Science. Of course, there’s plenty of beauty to be found off campus as well…

Here we see what might be called in the travel brochure “the beautiful natural scenery of the Texas Hill Country.” West Austin is incredibly hilly and crisscrossed with streams and rivers running from Lake Travis through the city and eventually into the Gulf. It’s a great area for a relaxing drive and there are plenty of scenic viewpoints like this one to get out and just enjoy the view.

Photos courtesy of Caity Collins

Adventures in Culture Shock: The Texas State Fair

As a leading department in the field, UT Sociology attracts a diverse body of graduate students from around the nation and the world. But no matter where they come from, they bring with them two things. One is a vision of Texas shaped by history, cultural stereotypes, and mass media. The other is a keen analytic and imaginative eye shaped by an active sociological imagination. These two facts met head on recently as graduate students Robyn Keith, Katie Jensen, Caity Collins, Eric Borja, and Dan Jaster took a road trip to the Texas State Fair. They each offered some personal thoughts on the scene they witnessed there. And of course, as per Texas State Fair tradition, their thoughts were immediately fried.

Robyn Keith: Since most of our October had been in the 80s here in Austin, it was a relatively chilly day with a high of 55. Wrapped in our pea coats, jackets, and scarves, we walked around and experienced all that the state fair had to offer. At one point in the hustle and bustle, a friend of ours turned to me and joked, “I have to wonder, if someone from another country came to this, how– how would they– how would you even know how to explain what a state fair is?” For a few minutes we tried to come up with an answer, but I have to wonder if the “ritual” of the Texas State Fair is in some way indicative of what we value here in Texas and, more broadly, the United States. Here is what I learned from the Texas State Fair:

1) Let’s buy stuff! Not even fifty paces into the fair grounds, we were bombarded with different products we could buy. Consumerism was rampant. Among the products we

encountered were power tools, copious amounts of beef jerky, turquoise jewelry, waterless cookware (we still don’t know what that means), and even a jacuzzi the size of my living room. What was once the “Hall of Varied Industries” at the Dallas Fair Grounds is now the Automobile Show Room. One outdoor area was dedicated solely to what seemed like hundreds of American made trucks, and prominently featured a truck atop a rotating 60 foot tall pedestal, panopticon style.

2) Everything’s Everyone’s bigger in Texas.You can find an astonishing variety of fried concoctions at the Texas State Fair. My personal favorite was a toss up between the Fried

Chicken and Waffle on a Stick and Fried Oreos. I also ate arguably the best corn dog of my life. That said, this doesn’t do much for the obesity epidemic here in Texas. One banner I noticed called Coca Cola a “super food.” I didn’t see a single fruit or vegetable the entire day. Well, unless you count pizza as a vegetable. It’s probably not a good sign that the healthiest thing we consumed all day was a free sample of a heavily sugared mango fruit smoothie from McDonalds.

3) Who has control over the money? The Texas State Fair implements a system where you buy coupons using cash or a credit card under the guise that it makes things easier for fairgoers to buy food and play fair games. Frankly, I found the coupon system inconvenient, since you have to wait in line to buy more coupons that only come in batches of $20. You also cannot sell your coupons back, so at the end of the day I found myself with $13 of useless coupons.

Apart from making extra money off of fairgoers, I suspect that the coupon system serves another purpose: it prevents workers from stealing. Coupons are constantly moving around at the fair. At one point, Dan and I were among nearly a hundred other people waiting at a corn dog stall. The workers were swamped, and coupons were changing hands between customers and workers in a flurry. From a “loss prevention” standpoint, it would be relatively easy for a worker to pocket cash; but pocketing a coupon has no benefits. I felt this distrust was also racialized, because I noticed that coupons were not used for the mostly white independent vendors in the convention centers, but always used for playing games and buying food, where workers were mostly people of color. Ultimately, the only people that the coupon system benefits are those in charge of the fair.

4) We like (the idea of) Farmer Joe.One area of the fair was set aside specifically for different representatives from the agricultural lobbies. One prominent dairy company had

beautiful (non-dairy) cows for display. Another passed out free nachos. Another section of the fair was for animal showcasing. All of the cows, donkeys, pigs, sheep, horses and even rabbits were meticulously prepared and gussied up for display.

Sociology aside, it’s hard not to have a good time when you’re petting a donkey or laughing about the ludicrousness of a fried bacon-wrapped cinnamon roll. And while Big Tex is no longer with us, I’m glad that we got the opportunity to see him together.

Katie Jensen: First, let me officially document our food consumption for the day:

Turkey Leg, Funnel Cakes, Frito Chili Pie, Fried Chicken and Waffle on a Stick, Corn Dogs, Fried Jambalaya, Fried Cookie Dough, Fried Pizza, Curly Fries, Chicken Fried Steak Sandwich, Fried Oreos, and last but not least, Fried Cake Balls

I can’t help but consider what wanting to present this laundry list of consumption means, our CV of fried food intake. It seems to embody much of what we accomplished and experienced at the State Fair, but how unnerving that I first want a methodical list reproducing chronologically the food we put into our bodies as primal testimony to having had the ‘Texas State Fair’ experience. Brings interesting questions to how we register experiences. Food for thought!

State fairs seem to be one of the only places in the world to unapologetically merge seemingly disparate interests – pride in agricultural production, product placement and advertising, games and rides, cultural performances, and conspicuous food consumption.

Maybe not so disparate? And Texas is no exception. While Big Tex (R.I.P.) looked down on us, we traversed rows of bunnies and cows and goats and sheep and horses. I even played a corn “videogame” most certainly sponsored by corn lobbyists that showed me all the wonderful things corn byproducts are in. Animal-based competitions included donkey-drawn-buggies led through obstacle courses complete with painted river. Upon entering, some in our group signed up with Reliant for free Fay-Bans. I believe I saw sufficient evidence to argue that there were more company stands – for everything from whirlpools, mattresses and Texas dairy products to trucks, gardening tools and welding workshops – than even food vendors. The Fair had lots of opportunities to try your hand at carnival

games for giant stuffed animals, and the same rides I remember from childhood – some of which I swear hadn’t even updated their spray paint graffiti decor; they still showed stars like Nelly and Nicholas Cage, not to mention generic portraits of overly sexualized scantily-clad women. But entertainment also included many shows and stages, with children of seemingly any and every ethnic group performing their traditional dances (what does tradition mean to children?), and a variety of musicians playing all day. The first food purchased that day was a turkey leg, which couldn’t help but get me to feel like the old cartoon sketches of cavemen. There were giant butter sculptures. Dan did an excellent job of documenting the array of fried food options available, more than any one human could try in multiple visits.

Caity Collins: A disappointing dearth of cowboy boots. A lamentable lack of hats. And an unfortunate insufficiency of oversized belt buckles. These were my first observations upon entering the fairgrounds at the Texas State Fair in Dallas a few weekends ago. Where the heck was all the cowboy attire?! Just as my Texan students ask me routinely about covered wagons and hippies when they hear I’m from Oregon, I still associate Texas with all things Western. I assumed that this stereotype (and blatant overgeneralization) would hold most true, if anywhere, at the Texas State Fair. Wrong I was. All seven of us friends attending the fair made an effort to dress somewhat Western, whether with a plaid shirt, boots, or our bluest pair of Levi’s. We learned a little too late that we’d put considerably more effort into this themed day than any of the fair’s other attendees. We spotted a few ranchers when we visited the livestock stables, but the vast majority of fairgoers were dressed in everyday attire, with no nod to the glory that is western clothing. Note the apparel here, in the shadow of Big Tex. I spy one lone cowboy hat there in the distance.

Eric Borja: As both Katie and Robyn have described, Capitalism was in full force at the

Texas State Fair. And as an Orthodox Marxist myself I really only have one thing to say about that…”OF COURSE!” Of course there were companies pushing consumable goods as we were pushing fried deliciousness into our pie holes. Of course there were cultural performances celebrating diversity as someone was trying to sell me a hot tub.

Of course, of course, of course Capitalism was to be found at the Texas State Fair.

Of course there were Anti-Obama billboards with racist undertones and Christian values on the I-35 as we made our way up to Dallas. Of course I saw huge trucks flying by on the highway with Pro-Gun or Pro-Life bumper stickers. Of course I saw a lot of ‘skinny

challenged’ individuals.

Of course, of course, of course this is Texas.

Of course there was a lot of diversity. Wait? What? Yes, you read it. The Texas State Fair was surprisingly diverse. It was not full of gun-totting, Republican voting, Ford Truck driving, Pro-Life ‘rednecks,’ as I’m sure all of us have secretly thought are the people outside of the ‘Austin Bubble.’ My Prius was not a hybrid island in a sea of gas guzzling SUVs and Trucks. I was not the only Brown person at the State Fair.

By far, the most fascinating thing about the State Fair, was its diversity.

Coming soon: a Sociological lens on Austin

SOC Talk:

Stratification and the Multiplicity of Sociologies

Isaac Sasson

Introductory courses on stratification, at both the undergraduate and graduate level, typically include a discussion of the classic correspondence between Kingsley Davis & Wilbert Moore and Melvin Tumin that took place over the pages of ASR between 1945 and 1953. I was originally exposed to this theoretical debate, which may well be one of the most famous in the history of sociology, in an Introduction to Sociology class during my freshman year in college. I distinctly remember the underlying subtext demarcating Tumin’s conflictual arguments as superior to the functionalist approach of his contemporary peers. Structural-functionalism was dead to us before we even realized what it was.

Several years later I came across the same correspondence during a graduate seminar on stratification here at UT. The second time was only slightly different, as this time I read not only the two original articles but also Davis’ response to Tumin. This happened by pure coincidence – unintended by me or the professor who taught the seminar – as Davis’ response simply followed Tumin’s seminal paper in the very same issue of ASR. Intrigued by the continuing correspondence I went on reading the extra few pages, only a couple of mouse clicks away on JSTOR.

In any case, the slight difference of reading the response to the response transformed it, at least for me, from an almost “evolutionary” sequence of theories to a living, breathing, and contested correspondence. I have to admit, I found Davis’ response to be quite dull – except for one major argument. According to Davis, the disagreement with Tumin stems from a misinterpretation (or an alternative definition) of the concept of stratification. While Davis & Moore’s original article focuses on the question of stratification of social positions, Tumin’s article focuses on the stratification of individuals in society.

Some may argue that this is an artificial distinction, since as long as individuals occupy social positions only as much as they “fit” their social class, race, gender, or social roles, then the stratification of positions only exists to justify stratification of individuals. Still, Davis insists that stratification systems exist in every society and their goal (I purposely avoid using the word function here) is to promote motivation and efficiency. Here typically follows, and rightfully so, a barrage of critiques on the functionalist paradigm: who defines social utility and how, why are dysfunctional systems perpetuated if not for the interests of individuals and groups, teleological arguments that assign purpose to social structures that already exist, etc. etc. (there is no need to repeat the well known vices of structural-functionalism).

One question remains though – is there any merit to be borrowed from Davis & Moore, or do we only study them for the sake of refuting their claims? I’m inclined to think that they do not belong to the canon of modern sociology simply to provide a punching bag for conflict theory. The basic conceptual distinctions drawn by this historical debate still stand – that different mechanisms operate to create a stratified system of social positions on the one hand, and a differential placement of individuals in those positions. In fact, Davis & Moore claim in their original paper that societies characterized by strong inter-generational transmissions (of education, capital, etc.) will have low levels of social mobility and will fail in bringing the most able persons to the most important social positions (whatever they may be). This perspective does not undermine conflict theory, it simply points to two regions of conflict: how the system of positions becomes stratified and how individuals get placed in those positions.

In other words, we can view this multilevel stratification structure as an ideal type to which societies can be compared. Society “A” may conform to a high level of stratification of positions – measured by the distance between the lowest and highest social positions in terms of income or prestige – and at the same time allow for a high degree of mobility in placing individuals in those positions. Society “B” may conform to a more flat hierarchy of positions, but allow for a lower degree of mobility. In such society inequality may be lower than in the former, but placement of individuals in desired positions relies on inter-generational transmissions rather than individual merit. These distinctions, of course, have not eluded sociologists and can be found in many fields of study (e.g., inequality, organizations).

Another conceptual distinction made by Davis & Moore, which I find useful, is between esteem and prestige. The former refers to social approval an individual obtains through the fulfillment of his or her duties – regardless of how prestigious that duty is. Prestige, on the other hand, refers to the attractiveness of the social position an individual occupies. An important note here is that prestige is assigned to the position rather than the individual occupying it. Of course, these may not be independent of each other in reality: individuals may carry some degree of prestige with them long after they have “left office” (see Weber’s discussion of charisma for that matter), and conversely, their actions may affect the desirability and prestige of the position they hold in the long term.

Finally, I would like to add a few words on the “multiplicity of sociologies”. Every reading in sociology takes place in a social context: from the society you grew up in, through the academic department and tradition you’re a part of, to the level of the single class and syllabus where you encountered the sociological piece. The former president of ASA, Michael Burawoy, spoke in his presidential address in 2004 on the flavors of Sociology: professional, critical, public, and policy sociology. Without getting into strict definitions of the four “flavors”, I would argue that they exist in some combination in every department of sociology (as well as in every sociologist). For me, having been first exposed to Sociology abroad and in a very critical fashion, it will always be primarily a “peace disturbing science”, in the (freely translated) words of Bourdieu. Paradigms come and go and each leaves a dent in the discipline’s light cloak. If we revisit Davis, Moore, and Tumin for a moment, I’d like to say – give them a second chance. Not only do they provide a fascinating historical documentation of a paradigmatic shift, a near scientific revolution in the Kuhnian sense, they may also provide us with insights to use within the framework of critical sociology as well as the other flavors of sociology.

References:

Davis, Kingsley and Wilbert Moore. 1945. “Some Principles of Stratification.” American Sociological Review 10:242-249.

Tumin, Melvin. 1953. “Some Principles of Stratification: A Critical Analysis.” American Sociological Review 18:387-394.

Burawoy, Michael. 2005. “2004 ASA Presidential Address: For Public Sociology”. American Sociological Review 70:4-28.

Politics in Tunisia, Morocco and Iraq

UT Sociology Professor Maya Charrad talks with The American Academy of Political and Social Science about factors that contributed to the post-colonial developments of Tunisia, Morocco and Iraq, and the various elements at play in the Arab Spring: listen to the podcast here.

On Tunisia (from the interview): ‘[W]hat is really remarkable about the uprising in Tunisia is first of all what it is not…It is not military…[or] initiated from outside…[or] Islamic fundamentalist.’

Charrad says, ‘[I]n the Middle East what we see today is that the kin-based solidarities are not disappearing, they take different faces.’

Should the ‘Arab Spring’ be interpreted as a movement toward modernity (that is, a sort of ‘Berlin Wall’ moment of the Middle East), or is the reality something much more frenetic, uncertain–and potentially novel?

The work of Auguste Comte (1798-1857) has been widely influential, shaping everything from socialism and social reform, to scientific methodology, to even Russian literature and the creation of the French dictionary. Comte was also a founder (some may argue the founder) of sociology in the modern sense.

Comte invented the neologism ‘sociologie’ to cap his system of thought which he called ‘positivism.’ What is positivism, according to Comte? It is a systematic ordering of knowledge that is supposed to mirror and demonstrate the evolution of the human mind and world in general. Comte came on the heels of the French Enlightenment philosophes and physiocrats (Condorcet, Diderot, d’Alembert, Turgot), and of course the French Revolution, a time in which many scientific discoveries were being made in part due to advances in technology, and many new fields of knowledge (eg chemistry, biology and of course sociology) came into being. Accompanying the democratization of power was also a democratization of knowledge, and attempts to make sense of all these lines of fractures and developments.

Knowledge, Comte believed, was the basis of all human endeavor. However, he differed from fellow philosophers and epistemologists, such as his contemporary Hegel (he once sent his writings to Hegel, who replied in a very kind and diplomatically complimentary letter that Comte’s project perfectly complemented his own; Comte, however, later wrote to his friend complaining Hegel had completely misunderstood his thought). One of the unique things in Comte’s thought is that, instead of first defining what knowledge is, then going out to seek examples to fit that definition (ie prescriptively), he preferred to describe actually existing fields of knowledge, examine them and find out their relations to one another, which then he believed would reveal what knowledge really is.

Many critics of Comte and of ‘positivism’ (a term that would later take on many varying meanings) claim that, because of this, Comte wasn’t a very original thinker, ie he didn’t present some new metaphysical system, that he relied mostly, if not merely on the works of others. Yet Comte, in his work, specifically said that metaphysics—in short, the why’s of the world–must be overcome, out of which ‘positive’ knowledge—the how’s of the world–precisely, would emerge. For Comte, why something works is important, but not as much as how it works. (We can contrast it with Dewey’s pragmatism for further clarification: pragmatism doesn’t care how it works, just that it works. While for the pragmatist everything, ultimately, takes a backseat to action, for the positivist knowledge and action, or action and meditation, are always in tension with each other.) Therefore, he lay mathematics as the foundation of this ‘how,’ then physics, astronomy…and coined ‘sociology,’ which he also sometimes called ‘first philosophy,’ and placed it at the top, the pinnacle, the final growth, the goal and end of all knowledge. So, in other words, to ask what positivism is, is essentially to ask what knowledge is, and to ask what knowledge is, is essentially to ask what sociology is.

Comte then defined sociology as the science of human actions. It is in the domain of action, that science becomes a ‘social physics,’ or ‘sociology.’ Recall that Comte’s positivism describes precisely the relation of science to all human endeavor. So what is that relation? How do we get from knowledge to action, from what is called science, to the actual world? The link here, Comte claimed, is prediction. The primary function of science, and of knowledge, is to predict ‘what happens when/if,’ and that prediction is what actively shapes the world. However, Comte made clear what he meant by prediction (‘prévoyance,’ foresight, forethought, vision, wisdom) was not simply the application of a formula, of calculation based on an accumulation of known existents, but that it is essentially oriented toward the unknown, the inexistent or not-yet-existent, the ‘unpredictable.’ Prediction, for Comte, involves risk, and therefore, courage, as well as the imagination. We see here how Comte situated science itself squarely within the domain of ethics, not just as an add-on, a post-hoc, separate consideration–and yet, at the same time, it cannot be simply reduced to its political conditions.

If we were to take the economist Francis Fukuyama’s statement seriously, that History has not ended because Science has not ended (he had retracted his earlier statement about the End of History), and that one of the things that most presses and shapes our world today in terms of the issues we face depends on the very definition and role of science and scientists in society and for society, then the study and reevaluation of positivism, of where sociology came from, and where it should be headed, could not be more relevant right now.

Selected works

Comte, A; Martineau, H (tr). The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte. 2 vols. Chapman, 1853 (Cambridge reissue, 2009).

Secondary

Canguilhem, G. ‘Histoire des religions et histoire des sciences dans la théorie du fétichisme chez Auguste Comte.’ Études d’histoire et de philosophie des sciences. Vrin, 1968.

Lévy-Bruhl, L. La philosophie d’Auguste Comte. Alcan, 1899.

Macherey, P. Comte: La philosophie et les sciences. PUF, 1989.

Pickering, M. Auguste Comte: An Intellectual Biography. 3 vols. Cambridge, 1993, 2009.