by Maggie Tate

In The Aesthetics of Uncertainty (2008), Janet Wolff challenges the assumption that images exposing social injustice for political disruption must also abandon, or work against, standards of beauty and aesthetic pleasure. Her claims attempt to reopen the possibility that it is not inherently wrong to “provide aesthetic pleasure in the face of moral or political wrongs” (18). Thinking of aesthetic qualities is not often the terrain of Sociology, and for this reason Wolff raises more questions than her book alone can answer. It is, therefore, perhaps fitting that her most poignant suggestion appears in the title: approach visual imagery with an attitude of doubt, uncertainty, or incompleteness.

At the heart of Wolff’s project is the idea that at the very least, images are rich with sociological information and ought to be taken seriously. It was to this end that the Sociology department’s Race and Ethnicity Group and Urban Ethnography Lab collaborated on a photography workshop in late March. Traveling all the way from Leeds Metropolitan University, Professor Max Farrar brought his years of photographic experience to begin a discussion about what photography can add to sociological inquiry. The event included a talk on Friday, March 21, by Professor Farrar. This was followed by an all-day workshop on Saturday, March 22, led by the combined photographic expertise of Max Farrar and the award winning photojournalist, and professor, Donna De Cesare.

Farrar’s talk laid the foundations for Saturday’s workshop by engaging with theorists of photography, including Susan Sontag, Roland Barthes, John Berger, bell hooks and Les Back. Their theoretical work suggests a range of ways to consider the political possibility of the photograph. Susan Sontag represented the most critical voice with her claim of the danger inherent in the act of aestheticizing the political image therefore rendering it impersonal and unable to invoke empathy. John Berger’s ideas were also introduced as a critique of the depoliticizing effect of some photography, in particular photography that depicts human atrocity through pictures of agony and despair. Yet, Berger was also mentioned for his interest in photography’s ability to tell sociological stories by representing the universal in the particular. Photos of particular people provide images that become part of a collective social and political memory.

Amidst these challenges to photography’s ability to have political import, bell hooks’ writing provided a powerful reminder that the political is not always a measure of whether there is a change in public sentiment. Instead, she described the importance of the private space of the home as a site of personal self-definition, a privilege of which was long denied black Americans in public culture. Farrar’s own writing also asserts that the politics of photography are not just about reception, but lie also in the relationship that develops (or doesn’t) between the photographer and the photographed.

Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory of representation gave us clear language to describe the sociological relevance of photography through its transmission of myths. A photographic representation almost always stands in for broader ideological meanings. Yet, Barthes also recognizes the affective dimension of the photographic image, which is often the unexpected impact that a particular image or combination of images has on a viewer.

Therefore, the intention of the photographer is perhaps not always the most telling or sociologically relevant aspect of a given photographic image. This reveals one of the central tensions of the photograph; that it is at once a private moment frozen in time and a reproducible image that takes on a social and political life of its own. Les Back’s writing was referenced to remind us that these tensions can themselves become objects of sociological inquiry, such as the tension between detachment and intimacy that he reads in the photographs taken by Pierre Bourdieu during his fieldwork in the Algerian fight for independence.

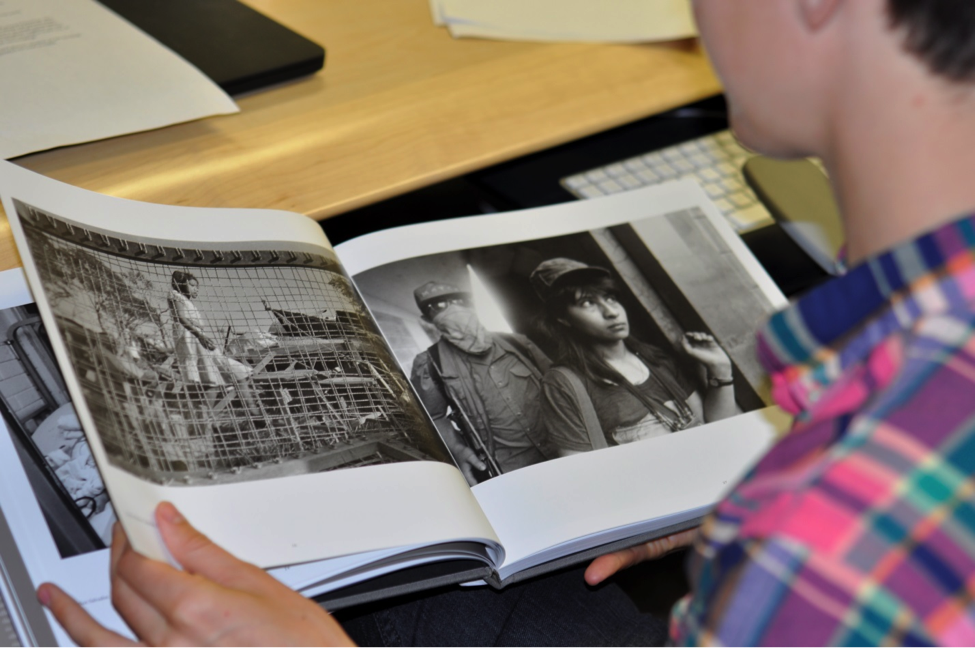

With this theoretical background, attendees of Saturday’s workshop spent the day trying to engage in these critical theories while also gleaning tips in photographic technique, methodological strategies, and rules of composition from both Farrar and De Cesare. Some of the distinctions between photojournalism and visual Sociology became at times more clear and at other times more blurry during these discussions. Through a presentation of photographs from De Cesare’s recent book Unsettled/Desasosiego (2013), attendees were given a window into the making of photographs that are both beautiful and complex. De Cesare’s photographs representing youths living amidst war and gang violence in Central America are heartbreakingly complicated in that they convey a wide range of emotion. They are at times peaceful, at times distressing, and most often an image will shift from the former to the latter as the viewer begins to realize what they see.

Thinking of De Cesare’s photographs in relation to Janet Wolff’s claim about the aesthetics of uncertainty, it becomes clear that the images are so emotionally provocative (and perhaps therefore so politically provocative as well) because they operate initially at the level of uncertainty and doubt. Captivated by the serene and sweet face of a young child, for example, the viewer only slowly begins to realize that the body lying on the sidewalk next to the child is a casualty of war. The composition created by the two figures is beautiful, but only because of the angularly distorted posture of the one lying down, which the viewer comes to realize, is lifeless.

From De Cesare’s photographs, we learned that indeed “beauty” and pain (“truth”) can exist simultaneously, and can be represented as such in a photograph. Not all photographs produced by visual sociologists need to meet this challenge in order to be insightful representations of social phenomena. Nor do they all need to be about pain in order represent the affective or political dimensions of doing sociological work. As Farrar has told me since, “photography is, basically, a relationship – between you and the person/people but also between you and the physical world.” Like all relationships, this one quickly becomes fraught with power dynamics, ethical concerns, aesthetic dilemmas and (perhaps productively) feelings of uncertainty.