by Connor Sheehan

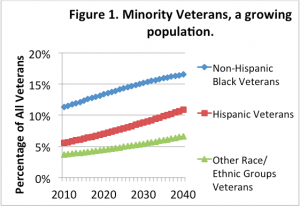

During the 2016 election cycle, Democratic and Republican candidates for president have consistently discussed veteran health issues and reform of the Veterans Administration (VA). The increased attention to veterans and their health is well-warranted, as veterans are an enormous population in the United States totaling over 23 million—almost as many people as live in the entire state of Texas. Veterans, of course, also have unique health, partially due to the occupational and behavioral hazards that accompany military service. As part of this policy discussion, it is important to discuss the large racial and ethnic health inequalities that exist among veterans. As I show below, racial and ethnic minority veterans consistently report worse health and have more health related limitations to activities than white veterans. These gaps are hard to ignore, particularly at a time when the veteran population is becoming increasingly racially diverse and the share of underrepresented groups among veterans is expected to increase dramatically over the next few decades (see Figure 1).

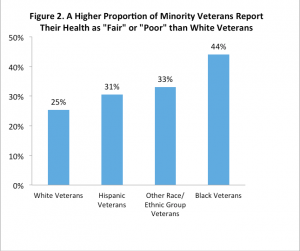

As a PhD student in the Sociology Department at the University of Texas, I have been conducting research that sheds some light on the extent and nature of racial and ethnic disparities in health and ultimately suggests what can be done about them. First, my findings consistently show that sizable health disparities exist. An analysis I conducted of a nationally representative survey of veterans administered by the VA showed that almost half of black veterans report “fair” or “poor” health rather than more favorable categories such as “good,” “very good,” or “excellent.” Conversely less than a quarter of whites reported “fair” or “poor” health (See Figure Two) (Sheehan et al 2015). The analysis also showed that 13% of black veterans report a severe activity limitation such as not being able to walk, get dressed, use a toilet, or eat. In contrast, less than 5% of white veterans reported having such limitations.

Not only are black veterans lives characterized by worse self-rated health, and more activity limitations, they are also shorter. In my own (unpublished) analysis using the Linked Mortality File of the National Health Interview Survey, I found that, even after controlling for age and region of residence, Black veterans were 43% more likely to die compared to white veterans from 1997-2011 (see Figure 2).

Imagine, so many of these veterans who once dedicated their lives to our country and sacrificed so much, are in such poor health. The American public and the presidential candidates cannot stand by and do nothing. The military, a longstanding institution that requires its members to uphold values like discipline, integrity, and loyalty should now uphold the same and do right by them. The VA, which shares similar values to the military and which also strives to provide equitable services, can also help minimize disparities.

There is a lot that can be done to reduce racial disparities in health among veterans. Any effort aimed at minimizing health disparities in later life must from the time that young recruits enter military service. My research shows that, compared to whites, a greater proportion of racial and ethnic minorities serve in combat roles, as well as also serving in branches with higher levels of exposure to combat and other dangerous experiences such as exposure to chemical or environmental hazards (Sheehan et al. 2015). Placement processes should be reviewed and such differences rectified in order to eliminate racial disparities in exposure to dangerous situations that have lifelong consequences for health.

Other researchers have shown that after military service, minority veterans attain lower levels of education and economic prosperity than their white counterparts – two components that are consistently linked to worse health (Teachman and Call 1996). To counter this, the VA could expand occupational training focused specifically on underrepresented groups, with the understanding that these programs may improve health.

Beyond these measures, there are also specific health interventions that could be used as models to design approaches that can help reduce disparities. One intervention which improved the overall health among a primarily black elderly veteran sample in Washington, D.C. relied on Home Based Primary Care (HBPC). HBPC emphasized the integration between social workers, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, and dietitians in providing care at home for the elderly population (see: Chang et al. 2009). Researchers found that those who received HBPC had 43.7% fewer hospital admissions and spent almost 50% fewer days in the hospital than those who did not.

Another intervention found that racial disparities in knee surgery outcomes were reduced when veterans were well-educated about their medical options. The black veterans who received more information on their treatment options experienced significantly less pain and greater physical function than black veterans who did not receive the information. There were little differences for the white veterans (Weng et al. 2007). These experiences suggest that integrating multiple domains and focusing on education regarding the health care system and health care options could help to minimize health disparities among veterans.

Veterans have sacrificed greatly for their country. Now it is time for their country to sacrifice for them, and work to end these health disparities. If the presidential candidates are as committed to veterans as their rhetoric claims, we should soon see policies and programs aimed at improving the health of all veterans.

Acknowledgements: I thank the Population Research Center, the Population Reference Bureau (Specifically Elizabeth and Reshma for their helpful comments), Shantel for her comments. All those working at the VA to end health disparities and all the veterans who have served. Mistakes and views are my own.

References

Chang, C., Jackson, S. S., Bullman, T. A., & Cobbs, E. L. (2009). Impact of a home-based primary care program in an urban Veterans Affairs medical center. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 10(2), 133–137.

Teachman, J. D., & Call, V. R. (1996). The effect of military service on educational, occupational, and income attainment. Social Science Research,25(1), 1-31.

Sheehan, C. M., Hummer, R. A., Moore, B. L., Huyser, K. R., & Butler, J. S. (2015). Duty, Honor, Country, Disparity: Race/Ethnic Differences in Health and Disability Among Male Veterans. Population research and policy review,34(6), 785-804.

Weng, H. H., Kaplan, R. M., Boscardin, W. J., MacLean, C. H., Lee, I. Y., Chen, W., & Fitzgerald, J. D. (2007). Development of a decision aid to address racial disparities in utilization of knee replacement surgery. Arthritis Care & Research, 57(4), 568–575.

Connor Sheehan is a fifth-year doctoral student in the Department of Sociology and the Population Research Center. His research analyzes health inequality and how institutions get “under the skin” to influence our health. Follow him on Twitter at @ConDemography.