by Juan Portillo

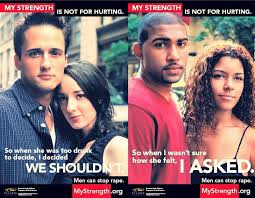

“My Strength Is Not For Hurting,” read a poster that professor Christine Williams showed during the inaugural MasculinUT: Healthy Masculinities Project event on September 3, 2015. Williams was critical of the poster because of how it positioned men as subjects who can make a choice to be violent or not, while women were portrayed as silent objects to be protected. The poster is an example of recent efforts to involve men in the movement to end violence against women, contained in Michael Messner’s new book, Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women. The book, which came out earlier this year, was at the center of an “author-meets-critics” panel conversation between Messner, UT sociology professors Christine Williams and Ben Carrington, and undergraduate Student Government Chief of Staff Taral Patel.

The conversation around this poster was reflective of the tone of the event, which did not focus purely on the successes or failures of men’s involvement in the movement to end violence against women, but on the contradictions and lessons that can be learned about masculinity, race, and the institutionalization of the movement to end violence against women. The “Strength is Not for Hurting” campaign represents, to varying degrees, the state of men’s involvement (or attempts to involve men) in the movement: a depoliticized (read: distanced from feminism), sanitized (read: not messing with a gender hierarchy or questioning masculinity), professionalized and institutionalized effort that targets individual men, but is not critical of masculinity or patriarchy and the way they shape institutions and their logics. It stands in stark contrast with MasculinUT, which is a project headed by Voices Against Violence of the Counseling and Mental Health Center. MasculinUT aims to transform taken-for-granted understandings of masculinity on campus, and promote healthy models of masculinity with the ultimate goal of preventing interpersonal, relationship, and sexual violence on campus. The conversation over the poster and the history of men’s involvement in ending violence against women went in many directions that problematized taken for granted ideas about gender, race, and violence. Though not all questions were answered, the fact that we can have a complex conversation says a lot about the direction that anti-violence work can positively go in.

Messner’s co-authored book analyzes men’s involvement in the movement to end violence against women from the 1970s to the present, separating the men into different cohorts. As Patel summarized during the event, Messner explains that in the 1970s some men listened to and collaborated with women who were leaders in the feminist movement, creating coalitions with them to redefine masculinity and fight for gender equality by reaching out to young men. Messner calls these men the “movement cohort.” Patel noted that a key difference between men in the 1970s and young men today was the use of political labels to identify themselves in the 70s, compared to almost a phobia of labels nowadays. The “bridge cohort” is what Messner terms the men who worked in anti-violence programs and institutions with anti-violence policies during 1980s and 1990s; Patel found this part of the book relevant to him as a student in an institution that has to follow laws and policies to prevent violence against women. Patel saw the institutionalization of anti-violence programs (in universities and the military, for example) as the success of feminism, and observed that coalition building means that allies must listen to movement leaders. He also highlighted how the book respects and centers the work of women, without which men who do anti-violence work could not operate.

The final group that Messner’s book discusses is the “professional cohort.” This cohort of men is the most diverse racially and economically; this is partly the result of anti-violence programs targeting communities of color and needing to recruit young men of color that their target audience can relate to. It is also a cohort distant from political discourses, as they do not identify with feminism for the most part, and work under a public health and social work umbrella to justify their involvement in anti-violence programs. In this vein, Patel’s questions focused on what students can do now to build on the opportunities afforded to them by feminist work and continue building coalitions that recognize how gender violence is not independent from racial violence and class violence, among other types of violence experienced by students.

After reflecting on Patel’s comments and Messner’s responses, I see that MasculinUT is a mixture of both “new” and “not so new” ideas. Mesnner shared that in the 1970s, men had a vested interest in changing the definition of “manhood” to humanize men and fight against unquestioned gender assumptions (which society ascribes to boys and men) such as men’s aggressiveness, lack of emotions, and violent tendencies. Like Messner’s early experiences in the feminist movement, one of the goals of MasculinUT is to promote healthy models of masculinities that would afford young men on our campus a better quality of life by improving relationships, reducing violence (against women and among men), and improving men’s mental and physical health by encouraging the exploration of different emotions and interpersonal skills often thought of as feminine.

However, as Christine Williams pointed out during the panel, recent efforts by some men’s groups who stand against violence often reify the gender hierarchy by positioning men as subjects who have to be responsible for their male power, and women as objects to be protected. After showing the posters mentioned at the beginning of this post, she congratulated Messner on how the book operates with a framework that does not glorify or put down men’s efforts, but rather works to understand contradictions and tensions that arise out of men’s involvement in the movement to end violence against women. One of her most critical questions had to do with how much emphasis Messner puts on education programs to reduce violence, and whether or not education is a true site of transformation for masculinity. To this, Messner responded that education by itself is not an answer, and indeed it is wrought with problematic messages that rest on a gender binary and hierarchy. However, he pointed out that the book contains examples of men using educational and promotional materials as tools to start a conversation that is relevant to men’s lives. Moreover, he emphasized that the book also explores what it takes for men to get interested in the movement to end violence against women, and how much effort they have to put in to make it their career. By emphasizing this, he is not trying to glorify the men (who often are praised just for showing up to anti-violence programs), yet also not dismiss the complicated, contradictory, and often difficult work they engage in.

Professor Ben Carrington also highlighted parts of the book that discussed how anti-violence PR work is limited when the movement to end violence against women is institutionalized. Carrington reflected on how, as universities, non-profits, health organizations, and other institutions develop anti-violence policies and work to reduce gender violence, they often ignore how to transform powerful entities (such as athletics departments) and become complicit in the perpetuation of violence. Moreover, Carrington mentioned that the problem is individualized, as it is not seen as a cultural or structural problem, but a problem of individual men. Often, the men who represent violence in the eyes of the institution tend to be men of color, who become scapegoats that ultimately allow for assumptions of masculinity within the institutions to resist transformation. Carrington ended with a question about the limits of Messner’s definition of the “field” of men’s involvement in the movement to end violence against women, particularly how limiting the genealogy of anti-violence work from the 1970s to today leaves out important contributions of women of color that span hundreds of years of work against the violence of European colonists, slave-owners, and other powerful entities. If these were to be included, asked Dr. Carrington, is a white, liberal, feminist framework still relevant?

There is a lot at stake when writing about men’s involvement in a movement primarily seen as headed by white women, because under patriarchy men’s contributions can be glorified and their privilege overlooked, silencing women’s needs and contributions. Moreover, in a society that privileges whiteness, it is easy to ignore women of color’s involvement and intellectual contributions in anti-violence work, and ignore power dynamics that result in men of color and working class men being labeled as the most violent in an effort to resist an overall transformation of patriarchy that affords elite men privilege. While the book does address some of these issues, Messner shared that after having conversations with many feminist academics and activists, he now sees loose ends left in his book. If given a chance, he would include more historical information about important anti-violence work, particularly work done by women of color. He explained that his original genealogy arose from a conversation with his co-authors while reminiscing about their involvement in the feminist movement and in violence prevention work. Thus, the genealogy represents their own social location. This reminds me of how Dorothy Smith1 and Patricia Hill Collins2 write about how the tools we learn as sociologists to conduct research are rooted in masculinist, Eurocentric logics. It is easy to forget or trivialize women’s intellectual contributions and work when the very tools of our field are already infused with logics that center (often white and middle-class) men’s experiences and standpoint, even when working with a feminist framework in a field constructed by feminists.

I am not accusing the authors of the book or pointing fingers particularly at them, but rather reflecting on what it takes to produce feminist work that includes sophisticated thoughts about men and masculinity in a feminist scholarly effort, from the point of view of men. As Smith and Collins argue, one way to account for the limitations of both our social location and masculinist, Eurocentric sociological methods and theory, is to trust and respect feminist work that arises from the experiences of women of all walks of life. This is something that, as a feminist scholar, Messner is doing since the release of the book. He has addressed questions such as Carrington’s by recognizing the limitations of his book and incorporating the tools and ideas of feminists of color to enrich the work without taking credit for those ideas. He wrote the blog post titled “Intersectionality Without Women of Color?” to engage in reflexivity sparked by listening to feminists of color. He starts his post by writing:

A book should never be treated as a statement of some final Truth. Instead, a book is best put to use as moment of condensed insight that focuses and clarifies ongoing conversations. Still, when you are the author of a book, and engaging in such public conversations, you sometimes learn things in the give-and-take that you wish you had known while writing.

This is where I see the success of this event and hopefully, of the new MasculinUT initiative on the UT campus: engaging in dialogue that results in meaningful transformations of our understandings of gender and violence, and the multiple intersections with race, class, and more. I foresee a lot of difficult conversations happening as Voices Against Violence moves forward with this project on the UT campus. When talking about the power inherent in relationships shaped by gender, race, and class (among other identities), and more importantly, about transforming those relationships to prevent violence, I don’t see an easy way to prevent disagreement or prevent MasculinUT from engaging in problematic discussions. What I do see is that it can be possible to have a dialogue where MasculinUT and the student body can learn from each other and together develop a fluid platform to address issues of violence, gender, race, class, and more. What this event taught me (in connection to feminist epistemology and methodology), is that this type of work requires an interrogation of logics and practices that exist through, and outside of, ourselves. We cannot rely on our experiences and our points of view alone to understand how violence works and how to prevent it. We need to trust, listen to, and respect what people with vastly different experiences have to say, whether this is in the form of theories developed by feminist scholars, or the solutions that activists of different backgrounds have come up with when engaging in anti-violence work. Being reflexive of our standpoint as we do research, having compassion for the people who engage in education programs that target men, questioning the rationalization for targeting men of color, and being critical of taken-for-granted notions of masculinity will only enrich the work that we do, and Messner’s responses (during the panel and in the blog linked above) are one way of transforming our narratives and our tools as sociologists. In line with his book, I do not want to glorify Messner for his work; however, I do want to celebrate the lessons to be learned in the contradictions and tensions that his work contends with, and the way that he listens to, honors, and works with other stakeholders in the movement to end violence.

References

1. Smith, Dorothy. (1987). The Every Day World As Problematic: A Feminist Sociology. Northeastern University Press.

2. Collins, Patricia Hill. (2000). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge.

—–

Juan Portillo is a Graduate Assistant for Voices Against Violence, working on the MasculinUT project. He is also a 4th year PhD student in the Department of Sociology at UT Austin.