The UT Sociology Department recently hosted a panel dealing with the struggles of students of color operating in an educational environment that can be both obliquely and blatantly racist. We will have a more in-depth discussion of the panel and the issues it raised with its creator Juan Portillo (pictured here) soon, but for now, we direct you to the article written by the Daily Texan concerning this important event.

Monthly Archives: October 2012

Social Logical : Texas State Fair

That’s one Huge Tex. Oh, right, BIG Tex. Anyway, in honor of our fallen flammable friend, and as an opening salvo in our blog’s new section, Social Logical Austin, click this link to follow the exciting adventures of some Texan transplant UT graduate students making their way in a strange new world: The Texas State Fair

Better Know A Sociologist: 10 Questions with Christine Williams

Here at the UT Sociology Blog, we strive to find new and interesting ways to expose the people and research in our department. To that end, we present to you “Better Know A Sociologist,” where we ask 10 general questions to one of our illustrious faculty members. Given that this is our inaugural post, we thought, “why not start at the top?” Thus we present to you 10 questions with Dr. Christine Williams, chair of the UT Sociology Department.

Here at the UT Sociology Blog, we strive to find new and interesting ways to expose the people and research in our department. To that end, we present to you “Better Know A Sociologist,” where we ask 10 general questions to one of our illustrious faculty members. Given that this is our inaugural post, we thought, “why not start at the top?” Thus we present to you 10 questions with Dr. Christine Williams, chair of the UT Sociology Department.

1. What first attracted you to sociology?

I don’t know how I first got interested in sociology. I’d always developed this narrative that I discovered sociology in college after going through different majors like political economy and art history. But then, somebody – I think my sister -pulled out my high school yearbook – I went to a pretty small high school in South America, so each senior had their own page and their own quote – and in my quote, I talk about wanting to be a sociologist! So I was 16 years old when I graduated from high school so obviously I knew what it was and I said I wanted to be one, so who knows? I don’t know where that came from in my 16 year old self, but I do remember actually making the switch to being a sociology major and I think it had a lot to do with the fact that it was the place where I learned about social justice and social inequality and that’s where feminism was located in the academy, so I think that that’s what drew me to the major. I’ve always been interested in class and gender.

2. What did you do your dissertation on?

My dissertation was a study of men in nursing and women in the Marine Corps. It was published as the book “Gender Differences at Work.” There’s this book by Rosabeth Moss Kanter that’s very famous called “Men and Women of the Corporation.” It’s a bit old, but people still talk about it. Kanter says in the book that it’s all about being a numerical minority, that is, the token phenomenon that results in basically labor force discrimination. I thought I would compare men’s and women’s experiences as tokens, but my original case study design was women in the Marine Corps and men in ballet because I had this title in my mind : “Men and Women of the Corps.” Like the Corps de Ballet and the Marine Corps, and I thought it would be this great hook because it was ultimately a critique of Kanter but I went to talk to an adviser in anthropology – who ended up not being one of my advisers – but he said that it was a stupid comparison and I got all, “Waaah, no!” I eventually figured out that he was right, but he was way too gruff in his manner and so I changed my case to nursing.

And so doing those studies, was that sort of what got you thinking towards doing the research that would eventually result in “Still A Man’s World”?

Yeah, after I had published “Gender Differences at Work,” one of my reviewers – it was actually Arlene Kaplan Daniels, who recently passed away. She mentored the whole generation of scholars that are my age. She was really really important and is missed – she gave it a very positive review and said that she was especially interested in the case of men because sociologists of gender have basically ignored men up until then and that the case of men in nursing was just fascinating and new and so that’s when I decided to expand my second book to look at more than one occupation that was female dominated.

3. Why did you decide to work here at the University of Texas?

Because they offered me a job! [laughs] Nobody picks where they work, this is where you end up. It was very funny because my first job was at the University of Oklahoma and that’s where I was an undergraduate. I was two years into being there and I was pretty miserable. I was the token qualitative person and the token theory person and it was just miserable, so I went back on the job market and applied everywhere. I almost didn’t apply here because I thought, “Oh UT, that’s going to be exactly the same as Oklahoma and I just want to get out of this part of the world.” But I came down here for my interview and I was just blown away. It was pretty and it had hills and people were really nice and excited about my work. I had just come from an environment where as an assistant professor I was constantly being criticized. Here everyone thought I was great and I thought they were great so it was a good match.

So when you got here, did you see this as a place you wanted to stay, or did you see this as just another part of your journey?

I had my career ups and downs here. I was pretty unhappy at one point because I thought they would count my two years [at OU] towards tenure and they didn’t – they would do such a thing now, but back then they had more stringent rules about time and rank – so they didn’t let me go up early and I was pretty unhappy about that and threatened to leave but never did. You know, I’ve been here for almost 25 years and I can’t – I often think about where I’d rather be other than here and I can’t think of any place. I can’t think of any place that would be as good as this. Of course I have this great lifestyle where I go away in the summer and get to live in the Bay area, so that kind of gives me the best of both worlds.

Definitely. Avoid the Texas summers if you can.

I know! But I still get to have the big ranch house and an easy bike commute and fantastic students and a great department.

4. What’s your overall experience of Austin then? What do you like about this place?

I like that it’s very relaxed and informal, although I understand that’s less so these days downtown. I just don’t go there. I think I, like a lot of people, live in a very small part of Austin. I basically live in a three mile radius of my home and I think it’s great. I don’t know what you’d want more than this. Of course, I spent a lot of my childhood traveling, so having a place that where I’m actually going to live for a long time is something attractive and very different for me.

5. If you could teach one sociological concept to the world, what would it be?

Mmm. Well it wouldn’t be the glass escalator, because I already did that and now I’m backtracking on that. There are flash cards with the glass escalator, it’s in hundreds of textbooks: kids all over the country are being given multiple choice questions on “what is the glass escalator?” So it’s happened.

So talk about that. It sounds like you’re a bit conflicted. How do you feel about having that sort of legacy or this concept that you created out in the world and you don’t really have as much ownership over how it’s being discussed and taught?

Well, it’s a good feeling. You know, I didn’t actually invent the term, [my partner] did. [laughs] I was sitting there working on the article because I had published two books already and my senior colleagues told me that if I wanted to get tenure at Texas I had to publish articles too. So I was working on this article that became the glass escalator article and I was looking at my analysis and saying “It’s like these guys keep on getting moved up even though they don’t even necessarily want to move up. It’s like they’re on some kind of elevator or something!” And he goes, “no, it’s an escalator, because they have to work to stay in place.” And I said, “That’s it!” I remember it very vividly, that conversation. So it’s very gratifying to know that – and I think it’s a good concept because people know intuitively what it means because it has a counterpart with the glass ceiling, and I do think that’s partially the secret to success is to come up with some catchy term. I mean, Arlie Hochschild really refined that with “the second shift” and “the time bind.” She keeps coming up with these great – like “the global care chain,” that’s another one.

Or emotion work.

Emotion work! I mean, all of these ideas, people can intuitively grasp what they’re about and it’s very cool. No, I’m backing away from it not because I think I was wrong but because I think that the world of work has changed so that there are many, many careers today that have no career ladder. You can’t have a glass escalator unless there is the opportunity for promotion. I think it’s a concept that’s grounded in an earlier form of work and we need new concepts.

It’s almost like a treadmill now.

Yeah, or a trap door is another one that we’re thinking about. So we’re thinking about the limitations of the glass escalator concept and we’ve got an article forthcoming in Gender & Society next year.

6. What’s the most rewarding part of your job?

This. Graduate students. Talking about ideas.

Why is that?

What other field do you get to be around a bunch of brilliant young people who are basically creatively thinking about society? There’s nothing else that comes close to it.

7. Who is one person in the department besides yourself that you think is doing really interesting work and what is it?

Well, it’s really funny, most of us don’t know what each other does, and I do because I’m chair. The thing that just boggles my mind is how much amazing work is being done here. When you asked that question, I was like, “Holy cow, what am I going to say?” I mean, is it going to be Sharmila’s [Rudrappa] work on surrogacy, Deborah’s [Umberson] work on gay marriage, Ron’s [Angel] work on post Katrina… It’s just endless. My colleagues over in the Population Research Center are also doing really interesting and innovative work, so I couldn’t pick. I mean, Michael Young’s work on immigrant rights, Ari’s [Adut] work on the French Revolution – I get to read all of this stuff – Gloria’s [Gonzalez-Lopez] work on incest, it just goes on and on.

It’s an embarrassment of riches.

It is, and it helps us to understand why we’re so highly ranked but it also has to do with our ability to interact with and mentor excellent students. Just having that intellectual stimulation – we didn’t always used to have that here and I think it’s something that we’ve cultivated and grown. Virtually everyone in the department is doing interesting work now. I mean, Joe Potter’s work on contraceptive health and health policy, it’s just, it’s first-rate and it’s so interesting.

8. What are your current research interests? What are you looking at these days?

Well, the short answer is women geoscientists in the oil and gas industry, but I think my heart lies in understanding work transformation and deindustrialization. What’s really interesting to me is how a lot of policies meant to promote gender equality have been designed with professional women in mind and I think that policies that aid them may actually diminish poor women. So I think there’s a real need to understand how social policies have a class basis to them. Especially poor women, but also men, because a lot of the time they’ll say, “OK, there’s a gender wage gap”. Yeah, she’s earning $7.50/hr, he’s earning $7.80/hr, so both of them are struggling, OK? It’s like it’s almost the wrong issue. And the focus sometimes on gender disparities at the bottom of the wage scale I think prevents worker solidarity. This is the stuff that I’ve been teaching to you since I first met you, sort of combining the gender and sexuality with the labor markets.

Exactly. And sort of the effect of neoliberalism towards putting men and women in a race to the bottom in terms of wages.

Right. And we can still detect gender disparities but are they the issue when people are not earning living wage? No, they’re not. On the high end, it’s “OK we’re going to get women into the CEO suite,” but it’s going be a pyrrhic victory if they’re just going to continue to impose these neoliberal reforms and slash any kind of benefits and wages. No thank you! That’s not my feminist movement.

9. What’s one book you’ve read in the past year that you’ve really enjoyed and why?

Well, the book I’m reading now is just amazing. It’s Sinikka Elliott’s book – which was her dissertation here at UT – and I’ve assigned it to my undergraduates. There’s just so many wonderful feelings involved in seeing this work from its inception. It’s called “Not My Kid,” and it’s about what parents believe about the sex lives of their teenagers. They all think that their kids are good and innocent and other people’s kids are hormone driven sex maniacs and this belief, she argues, reproduces social inequality but it also prevents teenagers from getting any kind of thoughtful, useful information about sexuality and relationships.

10. What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

I enjoy bike riding and reading. Especially novels. I also enjoying swimming and yoga and drinking beer.

A Crooked Piece of Time: As Navigated by Dr Sheldon Ekland-Olson

By Kevin Hsu and Evelyn Porter, with special thanks to Julie Kniseley

Professor Dr Sheldon Ekland-Olson shared his stories and lessons with students and colleagues today on the journey to becoming a sociologist, a scholar, a teacher, and a truly resilient human being.

Dr Ekland-Olson is the Audre and Bernard Rapoport Centennial Professor and Graduate Advisor of Sociology, and Director of the School of Human Ecology at UT-Austin. Former Executive Vice President and Provost of the University and former Dean at the College of Liberal Arts, Dr Ekland-Olson is the recipient of numerous honors such as the Texas Blazers Faculty Excellence Award and, most recently, the Regents’ Outstanding Teaching Award. He joined the faculty of the University in 1971 after earning his PhD in Sociology and Law from the University of Washington and Yale Law School.

Dr Ekland-Olson’s latest book Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Decides? (Routledge, 2011), based on his award-winning and hugely popular undergraduate course at UT, explores controversial issues such as abortion, neonatal care, assisted dying, and capital punishment, and the fundamentally sociological processes that underlie the quest for morality and justice in human societies.

In this talk Dr Ekland-Olson (or Sheldon, as his colleagues and students affectionately and most often call him) emphasized the importance of discovering and being self-aware about one’s core values and goals, of ‘knowing thyself,’ and staying true to oneself under various circumstances. Sheldon’s own personal and professional course has taken a number of unexpected turns, but at each juncture he asked himself whether his choices and actions truly reflected what he wanted to do and felt was right, and this has been his guiding principle to this day.

Against the backdrop of the American civil rights movement, Sheldon attended college in Seattle, originally intent on obtaining a bachelor of science in chemistry. In the summer before his senior year, however, he was hired by an anthropology professor to transcribe interviews with an 85-year-old member of the Kwakiutl tribe in Canada about the effects of modernization on his community. Sheldon admitted to catching the ‘ethnography bug’ while transcribing Jimmy Seaweed’s interviews, and in his senior year changed his major and eventually graduated with a bachelor of arts degree.

In part because of his science background, Sheldon went to graduate school at the University of Washington to study social statistics, and five years later he graduated with a PhD in sociology. It was during this time he began to see the importance of law and the legal system in effecting social change, and he applied for and received a postdoctoral fellowship at Yale Law School.

Sheldon remembered loving the study of law, which for him was a fascinating subject in and of itself. Despite strong pressures from mentors and colleagues to go into a law career, he was more interested in the interplay and dynamics between law and culture – in particular the lives of prisoners, who are systematically stripped of civil rights, existing in a sort of gray legal ‘no-man’s land’. He undertook an ethnography of jail, spending nights studying and talking to prisoners awaiting trial about their unique perspectives and experiences, which led to the establishment of a pro bono legal counseling service provided by law students to prisoners in need.

In 1971 Sheldon joined the UT Sociology Department. Just before his tenure review, the publisher of his ethnography study went bankrupt, and mentors and colleagues tried to persuade him to pursue other courses of research and to publish in different venues. Nonetheless Sheldon stayed true to what he was interested in, thought was relevant and wanted to do, and was eventually able to publish his book and earn tenure at the University.

In the 1980s the Chancellor of The UT System was seeking to implement higher education development initiatives in the Rio Grande Valley, and wanted a ‘non-bureaucrat’ to oversee the process. Sheldon was appointed as special assistant on this task force. It was then Sheldon discovered his love of, and knack for, building programs from the ground up. Later, as Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, he would apply his vision and experience to the creation of programs such as Plan I Honors, the Undergraduate Writing Center, a Religious Studies program, Freshman Seminars, the interdisciplinary Tracking Cultures program, and numerous other initiatives at the University. Sheldon emphasized his journey is a continuous learning process and he ended up doing what he loves in completely un-anticipated and un-preconceived ways. It’s been important for him to remain true to his goals, and yet recognize there may be many paths to reaching them.

In the late 1980s Sheldon’s mother was dying from diabetes. The exorbitant cost of experimental drugs that could prolong her life for possibly six months forced Sheldon’s father, a janitor, to make the difficult choice to let her die. End-of-life and quality-of-life issues have since intimately engaged Sheldon as a teacher and a scholar, leading him to develop his undergraduate course ‘Life and Death Decisions’ and, eventually, write his book Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Decides?.

Sheldon’s current teaching and research involve the study of the evolution of moral systems, from the way people justify torture and capital punishment, to how science and technology influence our morality and ethics, and vice versa.

In sum, Sheldon offers the following life lessons for resilience:

- Be grateful for rejection and adversity, and learn to cope with them. It is through them we come to realize our source of strength and learn where our anchors are. (Hrabal: ‘For we are like olives: only when we are crushed do we yield what is best in us.’)

- Be grateful for successes, no matter how small they may seem.

- Recognize small steps matter. Don’t plan too far ahead. Be open to unexpected developments and bends in the road, in study and in life.

- Have humor.

- Be responsible and live for yourself.

We are grateful Professor Sheldon Ekland-Olson has shared his stories with us, a testament to the adage that example isn’t another way to teach – it is the only way to teach. We are truly fortunate to have him here as a colleague, a mentor, and a friend.

Thanks, Sheldon!

Research Q & A – A Dynamic Duo of Crime Fighting: APD and UT Sociology

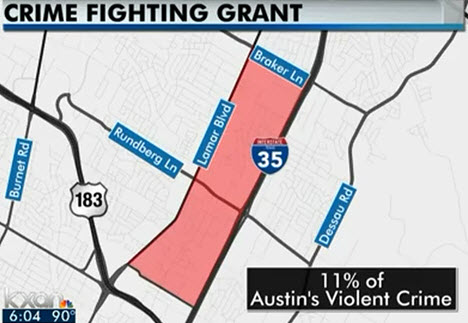

Recently, the Austin Police Department was awarded funding from The Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Program, a program begun by the Department of Justice to help facilitate place-based, community oriented strategies to address neighborhood crime. As part of their proposal, APD has involved the UT Department of Sociology in the planning and evaluation steps of this multi-year project. We sent our intrepid blog editor to interview Dr. David Kirk, Associate Professor and lead researcher on the project, to find out more.

Why did APD decide to involve the UT sociology department?

Well, they were looking for research partners that had some experience with community crime prevention and neighborhood development and I had contacts at APD who were aware of my research. A core piece of my research agenda is understanding the relationship between crime and community conditions. APD knew I was familiar with the White House Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative through some work I have done with the National Institute of Justice. So I am familiar with what the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Justice Assistance want to accomplish through this grant program. Additionally, given my research background, I can help them both design a crime prevention program and evaluate it after implementation.

This project is specifically focusing on the area north of 183 around Rundberg Lane. Why was this area targeted?

The nature of the grant program is to identify a neighborhood in a given urban environment that accounts for a disproportionate amount of crime in a given city. So when APD and I developed the grant proposal, we looked at neighborhoods where crime concentrates. Here in Austin, the crime rate is fairly low compared to the crime rate in other urban areas, but it’s very concentrated and the Rundberg area is one of the extreme pockets of crime in the city. So the decision was kind of made for us based upon the distribution of crime.

Are place-based crime strategies effective?

Definitely! The particular strategy that we’ll end up applying in the Rundberg area won’t apply everywhere of course, but certainly place-based strategies do work and not just in areas where there are high rates of crime.

One of the goals of this project is to not just reduce crime rates, but to “empower residents” of the neighborhood. Why shouldn’t these funds just go directly into enforcement and surveillance?

Because if you just spend the money on enforcement and surveillance it’s not developing community capacity like it needs to. So the idea is that after a three year period – a year of planning, a year of implementation, and a year of evaluation – the project funds will go away but the effort will be self-sustaining because the collective capacity of the neighborhood has been built up. It’s not just about reducing crime; it’s also about building collective efficacy in the community so that you have residents and the police and the DA and community organizations all working together. So we want to establish social network ties, establish working relationships; therefore even when the money goes away, they’ve got an institutional framework for continuing to fight crime.

What does “empowering residents” mean? What might it look like?

What does “empowering residents” mean? What might it look like?

It can be as simple as encouraging residents to report crimes or to start neighborhood watch programs. Yet a specific motivation for this grant program is to directly involve the community in the planning process. That empowers residents. They will work with city leaders, community organizations, and UT to analyze the problems in the community and figure out what solutions make sense. Ultimately, if we just rely upon the police to control crime then we’re not capitalizing on the fact that there are all these other entities that could help out.

So just to be clear, we’re not talking about empowering residents to fight crime themselves, we’re talking about empowering them to address the causes of crime and to reduce the crime rate in that fashion?

Well, I’m definitely not talking about vigilante justice where you arm residents and have them go out and fight crime! [laughs] But I AM talking about empowering residents to work with the police. For example, one characteristic of a lot of communities that have high levels of crime and socioeconomic disadvantage is that relationships with police are characterized by a lot of animosity and distrust. But if you bring the police and the residents in a collective process that’s designed to address community problems and they start talking, they realize it’s possible to reach common goals by working together. So part of the project is to work at reducing this distrust between the community and the police. And that goes a long way towards lowering crime.

That makes sense. What about the community of social services? How will they be involved in this?

They will be directly involved. One of the big issues in the Rundberg area – and this applies to a lot of urban neighborhoods – is concentrated prisoner reentry. You’ve got a lot of folks coming out of prison going back to neighborhoods and often times there’s not a great understanding of what kind of resources are available to help these folks reintegrate back into society and furthermore, a lot of the time the community itself may not even understand their needs. So we want to have the community communicating to individuals what kinds of resources are available. For example, “here’s an organization that provides job training for free,” or “here’s a treatment facility that actually has bed spaces,” or “I heard about this company that will hire ex-offenders,” that type of thing. So that’s one way to help facilitate the reintegration process for ex-prisoners. The theoretical idea is that if you have a structure of social service providers and non-profit organizations, these are important entities that can contribute to the control of crime.

Are projects like this common? A lot of times professors and academics are seen as “hands off” intellectuals, sitting alone in an Ivory Tower somewhere. Why is it important to be involved in on the ground projects such as this?

Well, different academics have different research trajectories. I have not done a lot of applied work. But this project is an opportunity to help a community and that’s certainly the most important thing to me. It’s interesting from a research aspect as well. There are research questions we can ask by trying to revitalize a neighborhood. I mean, the whole question of “can we get the police and the community and these other entities to work together effectively,” that’s an interesting question in its own right. It’s also important to research what it takes to foster better relationships between the police and the community. Personally, I definitely think it’s useful to apply what I’ve learned sitting here in my office running statistical models in the service of trying to help a community.

Anything else you feel is important that I may have missed?

I would just emphasize the nature of the three year project. It’s a well developed grant program that the Department of Justice has put together and so they’re providing the city and police and UT a year of funding to analyze the problem intensively. And then the idea is that after people have analyzed what’s going on in the area – and here we’re not just talking about crime, we’re also talking about housing, employment prospects, etc. – we’ll collectively come together and identify what types of intervention would make sense in the neighborhood. Then there’s the implementation phase and that has its own challenges. And then after that UT will come in and evaluate it and see whether or not it was a success. So it’s a big, three year effort. It’s going to present me with some different research challenges, but I’m excited. The Chief of Police predicted that there would be real change in the neighborhood. There are a lot of people interested in helping out the community and the community itself is interested as well, so I’m optimistic that we can make his prediction come true.

Cover Image provided courtesy of KXAN

“Comps and Defending Your Proposal: Secrets and Unexpected Benefits of the Initiated” with Jane Ebot and Christine Wheatley

Fifth-year student Jane Ebot and fourth-year student Christine Wheatley in the Sociology PhD program shared experiences and some cogent advice for fellow comprehensive exam takers and dissertation proposal defenders in our Thursday Brown Bag Session.

Jane took her exams in demography and is conducting research on maternal and infant mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. A PowerPoint version of her presentation can be found here. Below is a summary of her invaluable advice to students preparing for comps:

- In the semester before the one in which you plan to take your exams, check with your advisor and program coordinator on your degree progress and coursework checklist. With your advisor, decide if you are ready and when you should actually take your exams, in what area/s and sub-area/s you should take them, and who your exam chair and committee should be. Faculty often have colleagues in mind with whom they feel comfortable in working, and having committee members who can offer different perspectives but also get along personally can help you immensely, for comps and dissertation.

- After your meeting, create a reading list. Don’t reinvent the wheel. Build on past lists. Talk with other students in your area/s and sub-area/s, and remember, since your committee will invariably add a substantial chunk of materials to your list after review, that ‘less is more’. The list you propose to your committee need not be exhaustive. EndNote is also a great organizing tool.

- Organize. Put together a calendar (comps take place in mid-October and mid-April), and make a binder for your articles if your list is article-heavy. Make an outline/lit review template, and apply that template to each of your readings.

- Spend at least the two to three months preceding the exam reading. Divide and conquer. It is a good idea to save the hardest materials for last so you can remember them better before the exam.

- Be prepared for life still happening during all this. Prioritize and figure out what can wait, and discuss this with your mentors and colleagues particularly if you are collaborating on projects. Don’t neglect your health.

- Two weeks prior to the exam, review. This is the time to really synthesize your readings and suss out the relations among the items on your list. Try to find an overarching idea, and diagram it down to more specifics, to see if you truly understand your topic/s.

- Practice with past exams and/or imagined, anticipated questions. Many exams are written by the same faculty members. If you can, do so in the room where you will actually be taking the exam, even in the spot in the room – simulate the experience to prepare yourself and help yourself remember better. Do it first with notes, then without notes. Review afterward to see where you can improve. Talk to a friend, even a non-sociologist, and ask them to pose any questions to you about your area/s and topic/s.

- The day before the exam, relax. Sleep well.

- Show up early to your exam. Bring some quiet snacks and water (but not too much) if you’d like. You get one official short break on each of the two days of the exam; any other breaks you take will be on your own exam time. If your exam is in demography, you can also bring a calculator or use Excel on the computer.

- Outline and write your answers in essay form – major thesis-minor theses-evidence-restatement of thesis-significance.

After comps, it is a good idea to take a well-deserved break before you begin preparing for your dissertation proposal and proposal defense. To prepare:

- Discuss with your advisor about ideas, potential topics, directions, and methods for your dissertation.

- Write a five-page pre-proposal, and get feedback from your advisor.

- For the proposal itself, write a bit at a time. Make a calendar, and set deadlines for yourself. Don’t be afraid to ask for periodic feedback. Your advisor and you need to be on the same page regarding your readiness. Depending on your topic, your proposal may be 20 – 60+ pages. Again, work with your advisor closely through the process and clarify expectations.

- With your advisor, determine who should be (or should not be) on your dissertation committee. Remember you need one out-of-department faculty member.

- Email these potential members to request a meeting individually.

- Once they agree to be on your committee and you have your committee set, figure out a date, time and place for your proposal defense. Book a room right away, and confirm with your committee.

- It is a good idea to both email and give a paper copy of your proposal to all your committee members.

- Practice your presentation.

- Arrive early to set up the room and any equipment you need. Dress professionally. During the defense you will most likely present your proposal only for five minutes, followed by Q&A, discussion among the faculty, their decision, and further discussion with you.

Remember your proposal is just that – a proposal. Your dissertation may end up being more or less different.

While Jane focused mostly on the logistics of comps and and proposal defense, Christine Wheatley shared some excellent tips on managing yourself mentally and emotionally through these times, and through graduate school in general. Christine’s own research explores migrant experiences of deportation from the U.S. and return to Mexico. She suggests:

- Don’t see comps as simply another ‘hoop’ to jump through. Take it as an opportunity to familiarize yourself thoroughly with the fundamentals of your field and sub-field/s, in your own development as an expert and a scholar.

- Don’t rush through grad school. Competitiveness and perfectionism from fear and insecurity hinder more than they propel. Each person and each field are different; do what is right for you.

- Be self-aware about your own habits and disposition, and make them work for you rather than against you.

- Be prepared for your own emotional reactions. Almost everyone has thought about quitting or dropping out at one time or another. Reflect on whether these reactions are simply situational, and temporary.

- All your faculty mentors are here to help you. Your success is their success. Work with them and don’t be afraid to seek their advice and guidance.

- Overcome the Fear of the Unknown: practice, practice, practice.

- Read for the ‘big ideas.’ If some finer points do jump out at you, remember them and critique them. Understanding is the ability to differentiate between and to synthesize the big and the small. Session participant and graduate student Nicholas Reith also pointed out the importance of recognizing different perspectives, and it is a good idea to read more than one book review to get a balanced summary of a work.

- Remember to actually answer the questions on the comp exams. Restate the question if necessary in your answer. Don’t worry too much about ‘polish’ (but spelling and general intelligibility are still good ideas).

- Celebrate your successes! Make this into a cycle of positive, not negative, reinforcement.

A big Thank You to Jane, Christine, and all the participants at this brown bag for making it such a lively, informative and useful session!

From Mercenaries to Contractors

by Ori Swed

Upcoming presentation at Go-Betweens: Crossing Borders – An Interdisciplinary Conference at The University of Texas at Austin. Session B3: ‘Human Rights? Social Justice?‘ October 12, 2012. 3:40 – 5:20 pm. SAC 3.112

Contemporary conflict areas and warzones across the globe witness the emergence of an old actor in a new face-the hired guns. As the quintessence of the spirit of capitalism in the battlefield, the new contractors’ companies take an increasing part in modern battlefields. From a pariah and symbol of cupidity the soldiers of fortune turned into businessmen in suits and million dollar companies, transformed from mercenaries into contractors. These contractors and companies proliferate in conflict areas, conducting various tasks as partners of governments and armies, from logistics and maintenance to intelligence and even actual fighting. In many battlefields they outnumbered the standing armies’ regular soldiers. This is the result of an historical process and an old arm wrestle between the market forces and political forces that tilt to one side or the other. Nevertheless, current trends evince these new characteristics. This differentiates them from former times and raises interesting questions on accountability, while challenging the Weberian notion on States and the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence.

Contemporary conflict areas and warzones across the globe witness the emergence of an old actor in a new face-the hired guns. As the quintessence of the spirit of capitalism in the battlefield, the new contractors’ companies take an increasing part in modern battlefields. From a pariah and symbol of cupidity the soldiers of fortune turned into businessmen in suits and million dollar companies, transformed from mercenaries into contractors. These contractors and companies proliferate in conflict areas, conducting various tasks as partners of governments and armies, from logistics and maintenance to intelligence and even actual fighting. In many battlefields they outnumbered the standing armies’ regular soldiers. This is the result of an historical process and an old arm wrestle between the market forces and political forces that tilt to one side or the other. Nevertheless, current trends evince these new characteristics. This differentiates them from former times and raises interesting questions on accountability, while challenging the Weberian notion on States and the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence.

Not so long ago, in the mid-90’s, mercenaries such as ‘Mad’ Mike Hoare, Bob Denard, ‘Black Jack’ Jean Schramme, Yair Klein, and many others prowled all across Africa and Latin America; following the committing “tradition” of Ernst von Mansfeld, Roger de Flor, Francesco Sforza and many other respectable names. These individuals, though many times operating under the advice and request of governments, were considered pariahs in international politics. Even the surprisingly successful intervention of the South African mercenary company Executive Outcomes (EO), which forced the notorious Revolutionary United Front that menaced Sierra Leone to ask for peace, was concluded with rapid banishment by the international community the moment EO harbored stabilization and democratic elections. In spite of the mitigating effect of EO presence on the Sierra Leone civil-war, (which was an arena the international community failed to deal with) no one in the international community could envision that hired-guns run the security and indirectly, the politics of a UN member.

The world, post 9/11, presented more than a few challenges for the international community and especially for the only world power, which was occupied with two distinct and distanced arenas about half the size of Texas. After a quick triumph in Iraq and Afghanistan came the phase of control and reconstruction for two turn countries with bad infrastructure and unstable politics, a phase which demanded further ‘boots on the ground’ than the over stretched and exhausted coalition could supply. The solution came in the form of outsourcing; outsourcing of control, construction, and if necessary, of fighting (Chatterjee 2009).

|

Table 1. Comparison of Contractor Personnel to Troop Levels (As of March 11) |

|

| Contractors Troops | Ratio |

| Afghanistan Only 90,339 99,800 | .91:1 |

| Iraq Only 64,253 45,660 | 1.41:1 |

| CENTCOM AOR 173,644 214,000 | .81:1 |

Source: CENTCOM 2nd Quarter FY 2011 Contractor Census Report; Troop data from Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Boots on the Ground” January report to Congress.

Notes: CENTCOM AOR includes figures for Afghanistan and Iraq. CENTCOM troop level adjusted by CRS to exclude troops deployed to non-Central Command locations (e.g., Djibouti, Philippines, Egypt). Troop levels for non-CENTCOM locations are from DMDC, DRS 11280, “Location Report” for June 2010.

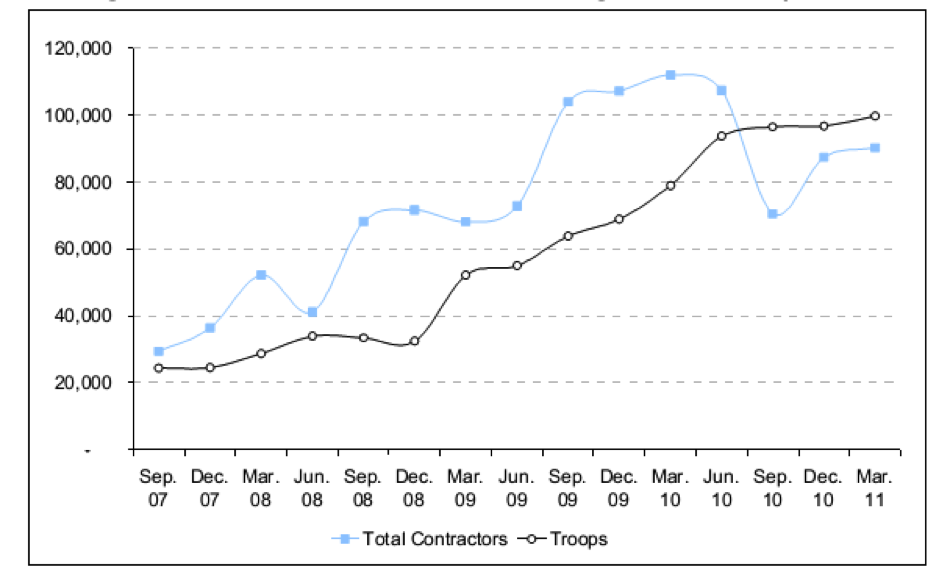

Figure 1. Number of Contractor Personnel in Afghanistan vs. Troop Levels

Source: CENTCOM Quarterly Census Reports; Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars, FY2001-FY2012: Cost and Other Potential Issues, by Amy Belasco; Joint Staff, Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Boots on the Ground” monthly reports to Congress.

Source: CENTCOM Quarterly Census Reports; Troop Levels in the Afghan and Iraq Wars, FY2001-FY2012: Cost and Other Potential Issues, by Amy Belasco; Joint Staff, Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Boots on the Ground” monthly reports to Congress.

This rapid ‘makeover’, from pariah into mainstream political consensus, took less than a decade. At present, contractors or private military companies (PMC), are the providers of a variety of services starting in logistics and catering and ending with intelligence gathering, security and sometime even offense. Western companies are not the only players in the market and many other companies are taking their share in the “scramble for Iraq and Afghanistan”. Many of them are local, especially in Afghanistan.

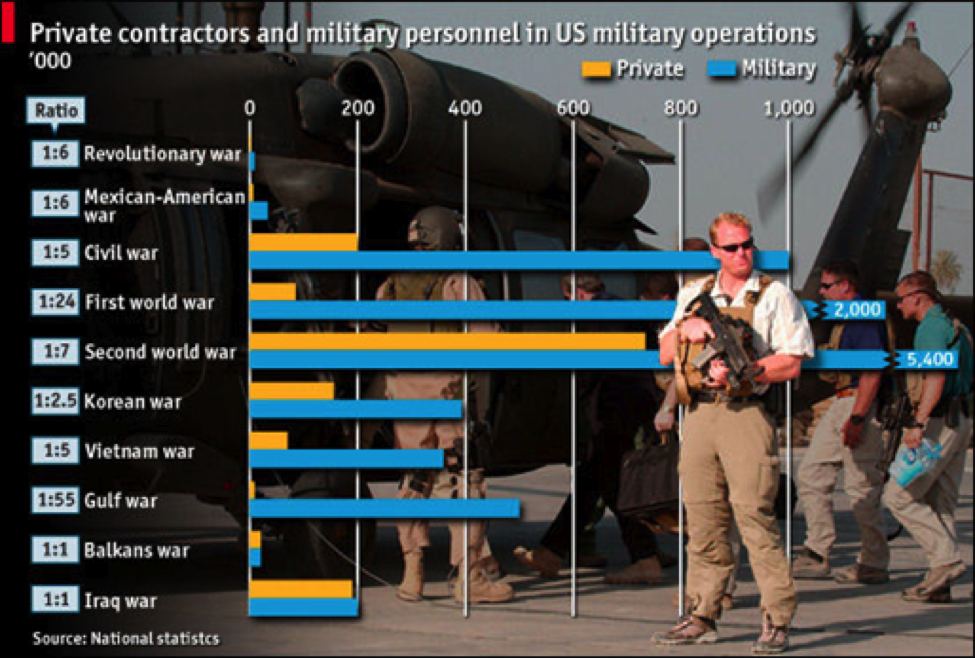

Comparing major American conflicts from the last 250 years yields interesting results. The ratio of mercenaries/contractors and troops in the battlefield increased dramatically and shows record highs of 1:1. Historically this trend is new in the U.S context, though it has historical precedent for other nations.

Source: http://www.economist.com/node/11955577?story_id=11955577

Source: http://www.economist.com/node/11955577?story_id=11955577

A ratio of 1:1 proposes that a significant military effort is conducted by contractors and not by military personnel. This trend raises points at issue over accountability and responsibility and questions the state’s ‘monopoly on the legitimate use of violence’. Take for example Blackwater, which retains a private navy, air force (it purchased recently a fleet of ‘Super Tucano’ turboprop fighting planes), and produces and sells its own armed personnel carrier- the Grizzly. Its capabilities surpass those of more than half of the UN members. Furthermore, in order to avoid the bad reputation associated with its activity in Iraq, the company rebranded its image and changed its name to Xe and later to Academi. Thus, we can see the dilemma of power and accountability (or problematic accountability) in the contractors’ contexts.

Currently, the interface between state/military and PMC’s is vast and not fully regulated. Problems occur frequently on the basis of determining jurisdiction and responsibility on the ground. Meanwhile contemporary warfare is changing as two distinct populations with different norms, characteristics, and organizational culture are working together, adding to an already complicated scenario.

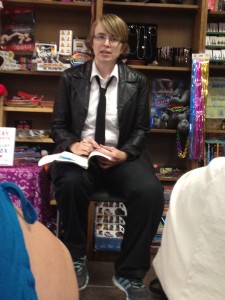

Timely Sociology: Gay Rights at the Ballot Box

On Tuesday evening, Dr. Amy L. Stone, assistant professor of sociology at Trinity University, gave a reading and discussion of her recently released book Gay Rights at the Ballot Box at Bookwoman, one of the many vibrant independent bookstores here in Austin. It was a great event well attended by UT sociology students as well as by the Austin LGBT community at large, and given the impending election, incredibly timely as well.

Outside of the Matthew Shepard & James Byrd Hate Crimes Act, which protects gay, lesbian, and transgendered people from crimes based upon their sexual or gender identity, LGBT persons have no rights codified on the federal level. As a result the LGBT community has engaged in a state strategy. This has led to some results, but these results are always vulnerable to recension and are heavily dependent on the sways of public opinion. Dr. Stone’s interest lies in the ways in which these state campaigns interact with the larger LGBT movement, and at times, how they reveal tensions between those who feel they may benefit from these rights and those who feel they may not (such as transgendered individuals and gays/lesbians of color).

To explore the interactions between national and state based activism, Dr. Stone researched over two hundred anti-gay ballot measures across the United States in a six year study. How do state based LGBT organizations fight discriminatory political measures? Stone’s work identifies three main strategies. One, they identify and mobilize. This can be as simple as “feet on the ground,” door to door activism in smaller states, or it can be a complex process of finding, tracking, and micromarketing to progressive voters in a large state such as California. Two, they create effective messaging. Early messaging focused on anti-gay measures as being invasions of personal privacy and infringements of “big government” onto the lives of individuals, but these met with little success. More recently the message has been that anti-gay measures are about discrimination, and Stone reports that this framing is much more effective. As Stone astutely pointed out to us however, the message is anti-discrimination, not pro-equality, as full equality is still seen as radical. And three, in states looking to pass enhanced Defense of Marriage Acts that would divest marriage rights from heterosexual civil unions and domestic partnerships as well as gays and lesbians, effective messaging makes the “Super DOMA” as much about the rights of unmarried heterosexuals as it is about same sex marriage. This takes the “gay” out of “gay marriage,” and as a result, the messaging is both highly effective and highly problematic.

More recently, anti-gay and gay rights ballot measures have expanded from states where ballot initiatives are common or where the LGBT community is demographically strong – Oregon or California, for example – out to heartland states. But unlike the former, the lack of prior ballot measures has meant these new states do not have the stable and robust activist organization that comes after a series of protracted political battles. As a result, these LGBT communities face an uphill battle fighting the measures and receive little support from national organizations, who see these campaigns as losing bets. Nonetheless, Stone demonstrates that while these battles indeed often end in defeat, the legacies are robust statewide organizations that prime the community and produce the structures for more effective political mobilization in the future.

Part of Dr. Stone’s analysis also looks at the ways in which the religious right has modified their argument against LGBT rights to fit the rapidly changing culture. Here we see a move from virulent, openly homophobic rhetoric painting gays and lesbians as deviant, possibly pedophiliac predators to more subtle messaging. For example, Stone related to the audience one ad where a young girl returns from school to happily inform her parents that “two princes can marry each other and I can marry a princess too!” The underlying message: big government is using public education to socialize your children into morals you may not agree with. Another ad Stone discussed highlighted a gay man opining that he doesn’t really need gay marriage, he’s perfectly fine with civil unions! Stone suggests that this ad works towards telling “on the fence” voters that it’s OK to vote against gay rights, that their ideals of equality and their desire to keep marriage “heterosexual only” are NOT in contradiction. (I found this line of messaging eerily similar to some presidential ads I have seen recently, where the focus is on convincing the independent white 2008 Obama voter that it’s OK to not vote for Obama this time)

In sum, Dr. Stone’s work offers one of the first truly comprehensive sociological analyses of state based LGBT political mobilization and as a result is an essential text for those interested in LGBT rights specifically or public policy generally. Furthermore, her attention to the interaction between national and state organizations should offer interesting data and insights for scholars of social movements and political change. A special thanks to Bookwoman for hosting such an informative and important event.

Gay Rights at the Ballot Box is available for purchase in Austin at….wait for it….Bookwoman (5501 N. Lamar)! For those not lucky enough to live in Austin, Gay Rights at the Ballot Box can be purchased at amazon.coms everywhere.

Our new home beginning Spring 2013 – a work in progress

Will we change the banner of our blog when we move into the new building next semester? Perhaps, but even more interesting will be the cultural changes we experience as we move into this monumental, very modern space. Many of us have become fond of Burdine Hall (I am among the sentimental) but as you can see below, even in this state of becoming, our new space is really impressive.

“Changing the Reputation of Rundberg”: APD Hires Sociology Professor in Community Reclamation Project

The Austin Police Department received a federal grant of $1 million to study and improve Rundberg Lane, an area that makes up 11 percent of all violent crimes in Austin. The money will be used to increase police presence and to hire The University of Texas at Austin Sociology Professor David Kirk for one year to research and plan a long-term solution. APD is one of seven police departments across the country to receive the grant as part of The Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Program.