by Ori Swed

Total institutions and their impact on those who pass through their gates have been the focus of sociological inquiry for some time (Davis 1989; Farrington 1992; Goffman 1961:1968; Scott 2011). One of the interesting byproducts of being an occupant of one of these institutions is the attainment of the institutional capital and its ramifications. This institutional capital, gained within the institution’s corridors, does not stay put or disappear when stepping back into civilian life. It becomes part of, and sometimes replaces, an individual’s social and cultural capital. What happens to the individuals who went through the total institutions’ re-socialization process, and who now carry alternative capital in their toolkit? Can this institutional capital operate outside of the institution? Does it have worth out of the total institutional environment?

For the most part, it does not. Not because it cannot, but because it requires a proper setting. It can translate well, however, in particular fields and or within groups and organizations that know how to utilize it.

For example, the military is a classical total institution that systematically, purposely, and officially re-socializes its occupants, erasing their civil identities and molding a military one. When veterans conclude their service, the re-socialization impact lingers. They still carry the institutional logic and norms with them to civilian life. Many times, this institutional capital is so potent that it can disrupt the re-socialization (or de-socialization) process back to civilianhood. Veterans often report reintegration difficulties, some related to the need to recalibrate their behavior and norms, or to remove the institutional capital and replace it with a civilian one. Nonetheless, since this capital is not an exclusive type of knowledge that is frequently shared with many others, individuals, groups, and institutions can utilize the institutional capital (in that case the military capital) for civil or economic purposes.

So, what is military capital? In Swed and Butler (2013), military capital was defined as the amalgamation of three types of capital bundled together: human capital (professional training), social capital (social ties), and cultural capital (social codes). This capital source is the total institution’s experience and the re-socialization process.

The Israeli case study presents an interesting example for the examination of the military capital utilization in the market. Israel is characterized by high percentages of veterans and their high levels of integration in the market and civilian life, which consequently serves as a good case study. Examination of the Israeli leading sector, the high-tech industry, reveals a strong correlation between military capital and job attainment in the industry. Two surveys of the Israeli high-tech sector (ICBS 2007 and Ethosia 2012) illustrate the profile of the Israeli high-tech sector employee: about 90% of the sampled population has military capital, as they served in the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

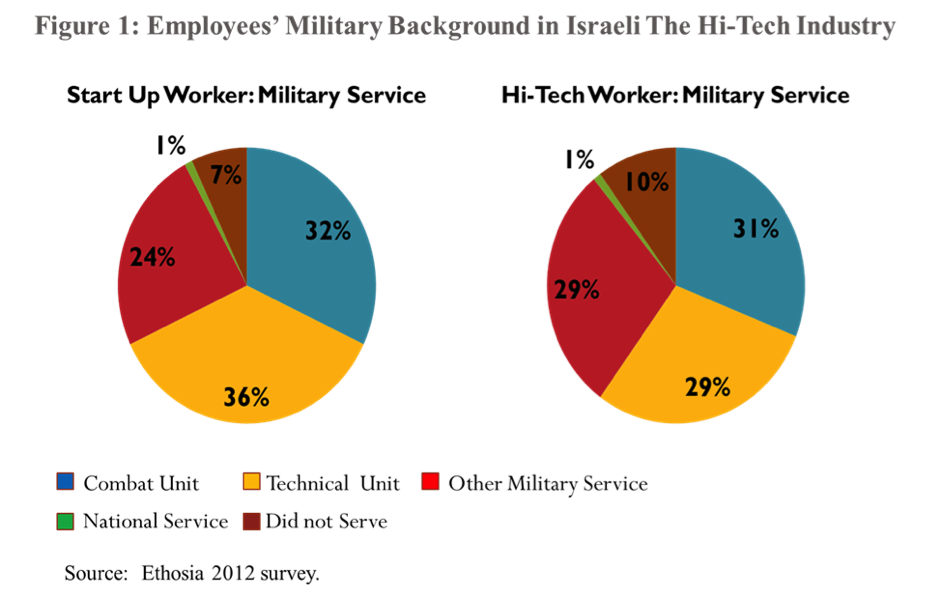

Those numbers are extremely high, even in a context where Israeli military service is mandatory. The actual veterans’ representation in the general population (across cohorts) is about 60%, and in the relevant age group it is less than 50%. A closer examination of the employees’ military background shows that around 60% served in combat or technological units (Figure 1). Those two types of units, which account for merely 20% of the general IDF servicemen, demonstrate very high representation in the industry. These units are known for going through intensive training that, in turn, generates higher military capital. These findings concur with the Honig et al. (2006) study on Israeli venture capital companies, showing that 85.4% of entrepreneurs are veterans with high military capital.

The Israeli high-tech industry is de-facto a military capital cluster that utilizes skills, networks, and culture for market purposes. As a result, the possession of military capital increases job attainment chances in the Israeli high-tech sector, while not having it diminishes those chances significantly. Further, the data shows that in the Israeli context, high military capital triumphs education, and has a positive impact on gender equality. Female representation in the Israeli industry (35%) is considered exceptionally high (for comparison, in the US high-tech industry it is about 25%). Examination of the female employee profile data reveals that the majority possesses military capital.

To conclude, taking into account the notion of military capital, or total institution capital, might paint a new light the examination of pressing issues in reintegration, market efficiency, and equality.

References

Davies, C. (1989). Goffman’s concept of the total institution: Criticisms and revisions. Human Studies, 12(1), 77-95.

Farrington, K. (1992). The modern prison as total institution? Public perception versus objective reality. Crime & Delinquency, 38 (1), 6-26.

Goffman, E. (1961). On the characteristics of total institutions. In Symposium on preventive and social psychiatry (pp. 43-84).

Goffman, E. (1968). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Aldine Transaction.

Honig, B., Lerner, M., and Raban, Y. (2006). Social capital and the linkages of high-tech companies to the military defense system: Is there a signaling mechanism?. Small Business Economics, 27 (4-5), 419-437.

Scott, S. (2011). Total institutions and reinvented identities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Swed, O., and Butler, J. S. (2013). Military Capital in the Israeli Hi-tech Industry. Armed Forces & Society.