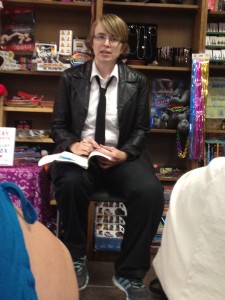

On Tuesday evening, Dr. Amy L. Stone, assistant professor of sociology at Trinity University, gave a reading and discussion of her recently released book Gay Rights at the Ballot Box at Bookwoman, one of the many vibrant independent bookstores here in Austin. It was a great event well attended by UT sociology students as well as by the Austin LGBT community at large, and given the impending election, incredibly timely as well.

Outside of the Matthew Shepard & James Byrd Hate Crimes Act, which protects gay, lesbian, and transgendered people from crimes based upon their sexual or gender identity, LGBT persons have no rights codified on the federal level. As a result the LGBT community has engaged in a state strategy. This has led to some results, but these results are always vulnerable to recension and are heavily dependent on the sways of public opinion. Dr. Stone’s interest lies in the ways in which these state campaigns interact with the larger LGBT movement, and at times, how they reveal tensions between those who feel they may benefit from these rights and those who feel they may not (such as transgendered individuals and gays/lesbians of color).

To explore the interactions between national and state based activism, Dr. Stone researched over two hundred anti-gay ballot measures across the United States in a six year study. How do state based LGBT organizations fight discriminatory political measures? Stone’s work identifies three main strategies. One, they identify and mobilize. This can be as simple as “feet on the ground,” door to door activism in smaller states, or it can be a complex process of finding, tracking, and micromarketing to progressive voters in a large state such as California. Two, they create effective messaging. Early messaging focused on anti-gay measures as being invasions of personal privacy and infringements of “big government” onto the lives of individuals, but these met with little success. More recently the message has been that anti-gay measures are about discrimination, and Stone reports that this framing is much more effective. As Stone astutely pointed out to us however, the message is anti-discrimination, not pro-equality, as full equality is still seen as radical. And three, in states looking to pass enhanced Defense of Marriage Acts that would divest marriage rights from heterosexual civil unions and domestic partnerships as well as gays and lesbians, effective messaging makes the “Super DOMA” as much about the rights of unmarried heterosexuals as it is about same sex marriage. This takes the “gay” out of “gay marriage,” and as a result, the messaging is both highly effective and highly problematic.

More recently, anti-gay and gay rights ballot measures have expanded from states where ballot initiatives are common or where the LGBT community is demographically strong – Oregon or California, for example – out to heartland states. But unlike the former, the lack of prior ballot measures has meant these new states do not have the stable and robust activist organization that comes after a series of protracted political battles. As a result, these LGBT communities face an uphill battle fighting the measures and receive little support from national organizations, who see these campaigns as losing bets. Nonetheless, Stone demonstrates that while these battles indeed often end in defeat, the legacies are robust statewide organizations that prime the community and produce the structures for more effective political mobilization in the future.

Part of Dr. Stone’s analysis also looks at the ways in which the religious right has modified their argument against LGBT rights to fit the rapidly changing culture. Here we see a move from virulent, openly homophobic rhetoric painting gays and lesbians as deviant, possibly pedophiliac predators to more subtle messaging. For example, Stone related to the audience one ad where a young girl returns from school to happily inform her parents that “two princes can marry each other and I can marry a princess too!” The underlying message: big government is using public education to socialize your children into morals you may not agree with. Another ad Stone discussed highlighted a gay man opining that he doesn’t really need gay marriage, he’s perfectly fine with civil unions! Stone suggests that this ad works towards telling “on the fence” voters that it’s OK to vote against gay rights, that their ideals of equality and their desire to keep marriage “heterosexual only” are NOT in contradiction. (I found this line of messaging eerily similar to some presidential ads I have seen recently, where the focus is on convincing the independent white 2008 Obama voter that it’s OK to not vote for Obama this time)

In sum, Dr. Stone’s work offers one of the first truly comprehensive sociological analyses of state based LGBT political mobilization and as a result is an essential text for those interested in LGBT rights specifically or public policy generally. Furthermore, her attention to the interaction between national and state organizations should offer interesting data and insights for scholars of social movements and political change. A special thanks to Bookwoman for hosting such an informative and important event.

Gay Rights at the Ballot Box is available for purchase in Austin at….wait for it….Bookwoman (5501 N. Lamar)! For those not lucky enough to live in Austin, Gay Rights at the Ballot Box can be purchased at amazon.coms everywhere.