Many thanks to the College of Liberal Arts Office of Research and Graduate Studies for hosting a broad based conversation on Resilience and Mental Health. Associate Dean Esther Raizen started the conversation by noting an increase in the number of graduate students who are seeking accommodations from the Office of Students with Disabilities. Kelli Bradley, SSD Executive Director confirmed that thirty four percent of new applications from over 240 graduate students cited mental health and anxiety related concerns.

Many thanks to the College of Liberal Arts Office of Research and Graduate Studies for hosting a broad based conversation on Resilience and Mental Health. Associate Dean Esther Raizen started the conversation by noting an increase in the number of graduate students who are seeking accommodations from the Office of Students with Disabilities. Kelli Bradley, SSD Executive Director confirmed that thirty four percent of new applications from over 240 graduate students cited mental health and anxiety related concerns.

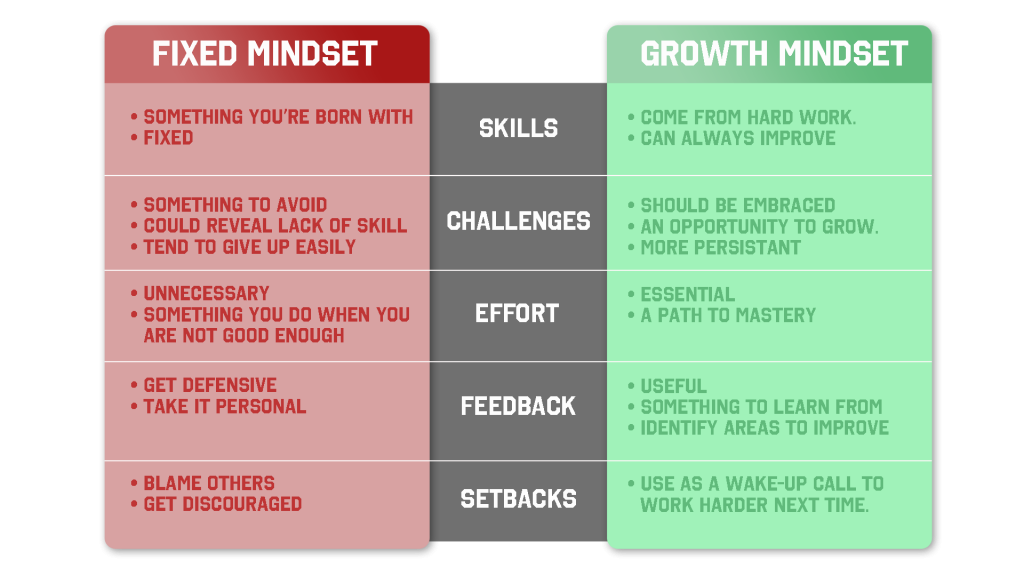

This is a steep rise in graduate student request for services that have traditionally focused more on undergraduates. Some thoughts on why graduate numbers also continue to rise at the Center for Mental Health Counseling include: fear of and the stigma of failure, financial and academic stress and more students who have been engaged with psychological counseling. To encourage self-care, CMHC has launched a new iPhone app Thrive at UT. Thrive consists of seven topic areas. Topics include community, gratitude, self-compassion, mindfulness, mindset, thoughts and moods. In each topic, students will find an inspirational quote, a short video of a UT student sharing their own story, some light reading and an interactive activity.

The job market may intimidate those who already carry the burden of student loans, including grad students who may not have a tenure track trajectory. International Students face additional anxiety stemming from language insecurity, living far from home and limited access to external funding sources. The CMHC also offers cultural adjustment resources to offset the potential for isolation, loneliness and depression.

Dr. Leonard Moore of the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement talked about the micro aggressions and feelings of being in a very small minority that students of color experience, both in their cohorts and in seeking minority mentors. He suggested admitting students of color who can cluster in cohorts, so they do not feel so alone. Encouraging students of color in administrative directions as well as tenure track positions would help to build a more diverse and inclusive culture in the academe and should be encouraged.

Susan Harnden, from the Employee Assistance Program recommended Susan Dweck’s Mindset, The New Psychology of Success as a resource for encouraging resilience in the face of challenges.

Dr. Gloria Gonzalez-Lopez has given talks on health and well being in the Sociology department, orienting incoming students as they transition into graduate school and encouraging them to find a balance between work and life. She shared tips on cultivating resilience as students face the challenges of completing their PhD.

Dr. Gloria Gonzalez-Lopez has given talks on health and well being in the Sociology department, orienting incoming students as they transition into graduate school and encouraging them to find a balance between work and life. She shared tips on cultivating resilience as students face the challenges of completing their PhD.

- learn to tolerate some suffering

- resolve to be healthy and have a real life while working on a PhD

- create a small network of good friends

- get a life, don’t forsake your humanity

- take care of yourself – sleep and eat

- schedule fun without feeling guilty

- have at least one supportive faculty mentor who really cares

- become more comfortable with uncertainty – transitions are a part of life

- keep the big picture in mind, the reason you came to make positive changes in the world

- learn to accept a certain amount of pressure and take breaks

- be receptive to help and advice

- cultivate basic emotional intelligence and be honest

- find your unique rhythm for productivity

- remember to reach out for help if you need it

- do not routinely overwork

- practice compassion for yourself and others

It is getting harder to avoid the feeling that our world is in turmoil. The tension between the old and the new can be overwhelming, particularly when uncertainty and negativity are part of the 24 hour news cycle. Cultivating the resources we need to survive and thrive during these time of transition are not only advisable, they are necessary. UT Austin has so many resources, for both the individual and the community, please use them and share generously.