That life is complicated may seem a banal expression of the obvious, but it is nonetheless a profound theoretical statement – perhaps the most important theoretical statement of our time.

-Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters.

by Eric Enrique Borja

For Dr. Sharmila Rudrappa’s Feminist Theory course the class was asked to bring in a photo or two for an essay we had to write. I immediately thought of two photos, only one of which I will show, which I took about a month ago for a photography workshop.

For the workshop we were asked to take seven to ten different photos of anything. The idea was to create a photo essay out of these seven to ten different photos and then present them at the workshop. When I originally took the photos I knew I wanted to capture “something” about my neighborhood, but that “something” was unclear. That is until I read Gordon’s book Ghostly Matters for Dr. Rudrappa’s course.

Gordon writes, “Ghostly Matters is about haunting, a paradigmatic way in which life is more complicated than those of us who study it have usually granted. Haunting is a constituent element of modern social life… To study social life one must confront the ghostly aspects of it” (Gordon 2008, 7). I realize now that what my photos were trying to capture were the ghosts that haunt me in my neighborhood.

This photo is of the Camino la Costa UT shuttle bus stop. It may look like any other bus stop, but for me this bus stop is haunted. Gordon writes, “The ghost is not simply a dead or a missing person, but a social figure, and investigating it can lead to that dense site where history and subjectivity make social life” (Gordon 2008, 8). For me, it is the ghost of the Austin Police Department that haunts this bus stop.

This bus stop is located across the street from where I live, so every morning I catch the CLC UT shuttle there. The funny thing about the CLC shuttle is that it was formerly the Cameron Road shuttle, but last semester Cap Metro decided to stop servicing my area – because a lot of brown people live in my neighborhood, so why help them get to UT, right?

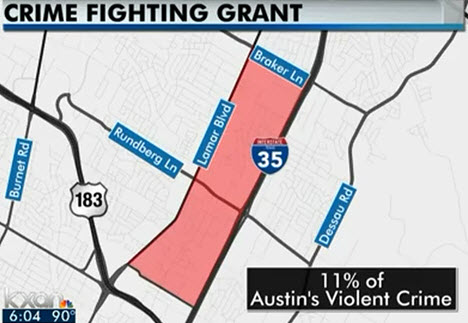

The neighborhood I live in (Census tract 1812) is located just off of Cameron Road, east of I-35, and south of Highway 183. Compared to the demographics of Austin, my neighborhood is overwhelmingly brown. The racial makeup of Austin is: Whites 48.7%; Blacks 8.1%; Hispanics 35.1%; Asians 6.3%; and Other groups 1%. My neighborhood is: Whites 14%; Blacks 15%; Hispanics 69%; Asians 1%; and Other groups 1%. A day does not go by where I haven’t seen and heard the police in my neighborhood.

Around this time last year, I was stopped, questioned and frisked by APD on my way to school. It was a cold rainy morning and I wasn’t feeling too well. So when I woke up I was debating between staying in and sleeping more or going to class. I decided to go to class about ten minutes before I had to catch the bus. I quickly threw on a hoodie, a pair of jeans, and shoes, and bolted out the door. As I came out of my house, I saw a cop across the street in his car.

I couldn’t really see his eyes, but my body knew he was staring at me. I ignored it because, why would the cops stop me? I was just going to school. I crossed the street and waited for the bus.

Directly behind the bus stop is a large parking lot for ITT Tech. The cop must have driven past me three times that morning, each time staring at me. Finally, he stopped and parked about ten feet away from me.

At this point I was really confused and nervous.

The bus came.

As I began to board the bus, the cop stopped me.

“Come here,” he said.

“Ok.”

As I approached him, I put down my hoodie and I began to recollect all of the things my father taught me when I got my driver’s license – be respectful, keep your hands where the cops can see them, and never give them an excuse.

I walked up to the cop, and he began questioning me

“What are you doing around here?

“I live here.”

“Where you going?”

“I’m going to UT. That’s the bus I catch.”

“What’s in the backpack?”

“My laptop and some books.”

By now there are three other cops around me. I showed the cop my ID, which has my home address – which, if you don’t remember, is across the street – but he is not convinced.

“Can you show me what’s in the bag?”

“Sure.”

I open my backpack and show him my laptop and books. Still not convinced I open my laptop, and unlock it to demonstrate to him that it is indeed my laptop. He’s finally convinced. He takes down my information and lets me go. As I walked away, one of the other cops said while laughing, “We’ll call you if you turn out to be the bad guy.”

At some point between me waiting for the bus and the cop questioning me, I almost ran back home to get my headphones. Imagine what the cop would have done if I ran back home that morning.

So, really it is two ghosts that haunt my bus stop: the Austin Police Department and me.

Life is complicated indeed.