From Dr. Ben Carrington’s Maymester Study Abroad trip to Leeds, England

Category Archives: University of Texas at Austin Sociology

Violence at the Urban Margins: Longhorns & Latin American Ethnography

Last week, the Department of Sociology – in conjunction with the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies, the Rappaport Cenntennial Professorship of Liberal Arts, and the Office of Graduate Studies – hosted a collaborative workshop that offered a space for students, researchers, and

professors to come together in the name of productive conversation, meaningful work, and camaraderie. The workshop featured the research of scholars from sociology and anthropology whose ethnographic work offers significant insights into the complex ways in which interpersonal violence is shaping the lives of those living at the urban margins in contemporary North, Central, and South America. Participants ranged from burgeoning new voices such as Matthew Desmond and Alice Goffman to the “giants in the field” Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Philippe Bourgois, who were featured in the final keynote session.

This workshop also functioned as a way for UT graduate students to meet these important scholars and read/react

to their work. To that end, students in Dr. Javier Auyero’s Poverty and Marginality in the Americas seminar were offered the chance to serve as discussants for the papers presented at the workshop. Your faithful blog editor tracked down a few of these upcoming intellectuals and managed to get some final reflections at the end of a productive, stimulating, and tiring week:

Pamela Neumann:

This past week I had the privilege of serving as one of seven graduate student discussants for a workshop on Violence at the Urban Margins. The workshop brought together a range of scholars to discuss ethnographic work in progress concerning violence in the Americas.

One of the themes that emerged during the workshop was the “moral economy of violence.” The moral economy of violence refers to the idea that the forms of violence that occur in a given context have their own particular logic, one that is shaped by specific historical, social, political, and economic conditions, but also by the perceptions and attitudes of the specific actors involved. Whether such violence occurs in the relative absence of the state or through the active presence of a hyper-militarized state can dramatically affect the localized meanings and functions attributed to different forms of violence, including which kinds of violence are deemed “acceptable” and which are not, For example, the violence perpetuated by a neighborhood gang may be viewed as a source of protection or danger (or both), provoking fear or solidarity depending on the precise nature of the interactions that gang members have with their surrounding community.

One of my takeaways from the workshop is that understanding the production of localized cultural logics concerning violence is a critical component of grasping its myriad effects in the daily lives of people located at the urban margins. However, explorations of these internal logics must be accompanied by similarly nuanced analysis of the political economy surrounding the incidence of violence. Such an analysis, as several workshop participants pointed out, must attend not only to the changing actions of the state (which are often quite contradictory) but also to a number of other factors, including: the contours of the international drug trade, the expanding role of international corporations, and the ways

that international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have circumscribed the available options for many governments throughout the developing world.

On a personal level, the workshop was an incredible space for intellectual exchange and spirited dialogue and reflection with other scholars, and I am very grateful that I had the opportunity to learn from them, and to participate in the conversation on this critical topic.

Jacinto Cuvi Escobar:

The workshop was fun and inspiring. Watching these big-shots fight over ideas (e.g. What is agency and why do scholars keep looking for it? Can some people lose it completely?) made me think of a wrestling contest – with some of the intellectual stimuli that the latter usually lack. It was a refreshing break from the studious and solitary routine of preparing for comps. And I enjoyed the opportunity to take part in the “fight” myself by discussing one of the papers. My favorite moment, however, took place during the evening, at Javier (Auyero)’s house, where the wrestlers were mingling in a much warmer manner, helped by beer and wine. I’ll never forget Philippe Bourgois mimicking himself as a graduate student, some thirty years ago, running after the agrarian reform in Central America – first because it was Philippe Bourgois, and second because it evoked the excitement and sense of purpose that any young sociologist should feel about her work.

Katie Jensen:

Participating in the Violence at the Urban Margins Workshop meant many more activities than just serving as the discussant on a presenter’s paper. It meant picking participants up at the airport; eating breakfasts, lunches and dinners together; driving speakers back and forth between their hotels and the conference. And it was this variety of opportunities to share ideas, laughs and constructive criticisms – about the conference topics, the academy, or whatever – that marked the highlight of the conference for me. I not only had the

opportunity to perform academically (serving as paper discussant and practicing my “elevator schpeel” while driving), but I also had the opportunity to share real, human moments – over Torchy’s tacos, coffees or as we meandered through Austin traffic – with scholars I hold in very high esteem.

While there are many moments to cherish from the conference for me personally, the workshop and its unique format I hope will continue to serve as an alternative model for academic engagement. That model worked to breakdown the hierarchies between junior and senior scholars, and spur collaborative dialogue. Many agreed they had never seen anything like it. Let’s hope it catches on.

Feeling the Body: Embodying Sociology at the CWGS Conference

Recently, the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies hosted a productive and stimulating academic conference entitled “The Feeling Body.” With the emerging attention the body and affect are receiving in research, this was a great chance for graduate students across disciplines to generate new conversations around the ways in which the body shapes knowledge. Below we offer brief abstracts of the eight sociology  students who presented work at the conference. Congratulations to the students, and congratulations to CWGS for another enriching and informative conference!

students who presented work at the conference. Congratulations to the students, and congratulations to CWGS for another enriching and informative conference!

Caitlyn Collins: “Some Girls, They Rape So Easy”: Conservative Discourses on Abortion and Rape in the 2012 U.S. Presidential Election

The United States has a sordid history of controlling women’s reproductive rights – ranging from forced sterilization to regulations on abortion. Most recently, the debate over abortion in the context of rape took center stage during the 2012 Presidential election. Republican politicians polarized voters by voicing their support for mandatory ultrasound laws, which would require women to have an ultrasound prior to obtaining an abortion, often vaginally using a probe – even for victims of incest or rape. Based on these lawmakers’ comments, what do the American people learn about conservatives’ opinions on women and their bodies? What are we taught to believe about women? And how might women feel in hearing these comments? I employ a feminist sociological perspective to examine Republican politicians’ comments during this past election in order to understand larger conservative discourses on abortion and rape. I examine six dominant themes in their rhetoric: pregnancy from rape is rare; sometimes women ask to be raped; sometimes women don’t know what rape is; some women lie about rape; legitimate rape can’t produce a pregnancy; and some rape is intentional because the product is a gift. I argue that these claims and larger discourses (a) are instruments of patriarchal social control over women’s bodies, (b) are forms of sexual violence and sexual terrorism, and (c) contribute to rape culture in the United States.

Juan Portillo: “You Better Not Get Pregnant!”: Epistemic violence and the regulation of Chicana students’ integration to higher education

In this paper, I center the brown, female bodies of six Mexican American students at The University of Texas at Austin as the site where social structures and ideologies are contested as they navigate a privileged space that has been imagined without them in mind (Puwar, 2004). I uncover the racial, gender, and class bias that members of the university take for granted by looking at the students’ identity formation and meaning making practices. I pay attention to their identity construction practices because these: (a) reveal the different strategies and cultural resources the students must use to overcome the racial, gender, and class barriers of the institution; and (b) reveal the racial, gender, and class microaggressions that students and professors perpetrate on the students to discipline and position them as subordinate. Concurrently, I look at the students’ experiences through a Chicana feminist lens, particularly Gloria Anzaldua’s (1987) concept of mestiza consciousness, in order to better understand their ambivalent and liminal social position. In addition, Chicana feminisms allow me to see the body as a site of potential theorizing (Cruz, 2001) and understand subjective personal experience as useful knowledge. As Paula Moya writes: “Since identities are indexical – since they refer outward to social structures and embody social relations – they are potentially rich sources of information about the world we share” (Moya, 2002, p. 131).

Shantel Buggs: “Your Momma is Day Glow White”: Questioning the Politics of Racial Identity, Loyalty and Obligation

Mixed race individuals in the U.S. consistently must negotiate their racial identities in relation to changing social contexts; the ability to shift and “perform” different racial identities has the potential to not only challenge hierarchical racial orders, but can cause strife within the individual’s family and friend groups. As Azoulay describes in Black, Jewish and Interracial, passing or identifying more so with one racial group can be considered a “rejection” of other racial ancestry. This project utilizes an autoethnographic approach to explore the impact of larger racial/ethnic categorization on the experiences of mixed race individuals in terms of individual identity and familial/cultural group obligation(s), focusing on an incidence of public policing through a popular social networking platform and the invocation of racial obligation by white friends and family members. I analyze how racism manifests within the interracial family, how racial loyalty and obligation are used as means of regulating mixed race identity performance and how these negotiations affect the mixed race individual.

Kate Averett: The Family as Assemblage: Toward a Queer Approach to Family Studies

Changes in family structure in the U.S. over the last several decades, including an increase in single-parent families and the increasing visibility of families headed by LGBTQ parents, have resulted in increased attention among researchers to the definition of family. This paper is considers the implications for theoretical understandings of the family for social scientific methodologies of family studies. Drawing on queer theory, particularly the work of Sara Ahmed, Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, and Jasbir Puar, I propose that in order to better understand the multiplicity of experiences of the family, social scientists would benefit from an understanding of family as an assemblage of embodied relationships. I argue that this approach to studying the family allows for a more intersectional approach to the study of families, one which takes into account the variety of embodied experiences that exist within families along axes of race, class, gender, sexuality, and age. In particular, I argue that such an approach allows more fully for an accounting of the experiences and contributions of children to family life.

Kristine Kilanski: When women “gain,” men lose?: An analysis of reader responses to news reports on the changing gender compositions of the workforce

In 2009, news reports were released announcing that women were about to outnumber men on nonfarm payrolls for the first time in U.S. history. In this presentation, I provide a brief overview of the push and pull factors that contributed to women’s increased labor force participation in the 20th century, and contextualize what this announcement said about the economic, historical, cultural and sociological moment in which it occurred. Then, I analyze reader responses to news articles announcing the changing gender composition of the U.S. workforce. The reader responses provide insight into the backlash women face when they are perceived to be making “gains,” and reveal longstanding stereotypes and cultural expectations of men and women’s “roles.” However, the comments also reveal alternative narratives about women and work, and that people are engaging critically with capitalism itself and the consequences of so-called economic “progress.” I argue that some of the media reports on changes to the gender composition of the workforce contributed to the false notion that the U.S. is a post-gender society, one no longer in need of feminism.

Anima Adjepong: What do you call a white woman with one black eye? Alternate readings of bruises on women rugby players

Conventionally, women, especially middle class white women, are expected to fit within a paradigm of heterosexual femininity that renders them meek and mild mannered. Bruises are a visible mark of a departure from norms of white heterosexual femininity. This paper explores the ways that bruises are legible on different women’s bodies. Using data from in-depth interviews with women’s rugby players, I ask players about their bruises and how they experience these bruises outside of a sports context. How do they interact with strangers and intimates who see their bruises? When players display their bruises, depending on how they fit into the discourse of passive heterosexual white femininity, they simultaneously challenge the idea that women’s injuries are a result of domestic violence and reproduce the idea that white women’s injuries are the result of violence perpetrated against them. The different ways bruises are legible on women’s bodies are imbued with racial and class stereotypes about the women who sport bruises. I employ an intersectional analysis to examine how white women who play rugby reproduce and challenge ideas about violence and femininity, and allow for a rethinking of the functions of white privilege

Letisha Brown: Through the Looking Glass: Sexual Violence, Body Image and Eating Behaviors in Black Women

This essay critically assess the research related to sexual violence, distorted body image, and disordered eating behaviors among Black women. While sociological research dedicated to the linkages between sexual abuse and eating behaviors among women is limited in general, it is especially sparse in regards to Black women. Using a Black feminist approach that utilized fictional representations—Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye—as well as autobiographies—Stephanie Covington’s Not All Black Girls Know How to Eat—in conjunction with scholarly research this essay makes the case that there is a growing need for research that pays close attention to these processes among Black women. A 2009 study conducted by Goree and colleagues revealed that African American, and low-income women, both Black and White, were at a higher risk to the development of and persistence in bulimic behaviors. This quantitative study, as well as the literature reviewed in this essay point to a need for qualitative research that focuses on mechanisms that lead Black women to bulimia including experiences of sexual violence, racism and discrimination.

Michelle Mott: Pain in Pleasure: Reading Racialized and Gendered Representation and Agency in Rihanna’s “S&M”

In this paper, I suggest that Rihanna’s song and video performance “S&M” is a playful acknowledgement and critique of the ways in which her sexuality gets taken up and portrayed in the processes of commodification of her as a black female pop-star. Using Black feminist theory and critical race theory, I argue that Rihanna’s performance can be read as an attempt to push back against the confines of the racist and misogynistic tropes that render black female sexuality as always and already degenerative and deviant and the historical practices of resistance that some have argued renders black female sexuality nonexistent.

Out of My Habitus – Why my education and manners get in the way of doing research

By Juan Portillo

Linda Tuhiwai Smith writes in Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples that Western academia has historically engaged in a process of legitimizing “what counts as knowledge, as language, as literature, as curriculum and as the role of intellectuals” (Smith, 1999, p. 65). This process happens in an environment that envisions

researchers, data and the research process as cultureless and bodiless, “floating brains” if you will. The danger of doing research without thinking where our bodies and experiences fit in the process (with all of our privileges and disadvantages) is that our biases as humans will make it into our final conclusions, reproducing an intellectually stagnant body of knowledge that at best is very limited in its creativity and explanation, and at worst it has the potential of marginalizing the people we are writing about.

One way to address our limitations and acknowledge our humanity is to really think about our social location and our role as researchers. Pierre Bourdieu’s habitus is an excellent concept that can help to explain this dynamic and can prevent us from completely divorcing our bodies and biases from the research process. As researchers, we are embedded in a social landscape that has provided us with dispositions that help us make sense of the world around us. Our habitus also provides us with the manners through which we express ourselves, inevitably reproducing

our class, gender, sexuality, ability, race/ethnic identity, etc. However, we don’t always pay attention to how our disposition and manners affect the way we interact with and learn from the data we collect or the people we interview and observe. I am starting this blog series in an effort to provide a tool for researchers at UT Austin to practice reflexivity and improve their interpretations of their research as well as their interactions with research participants.

While it is hard to really analyze ourselves and identify our class, gender, racial and other biases, sometimes situations arise that give us a chance to put ourselves under the microscope. We may enter a classroom, a restaurant, an interview or a lab where suddenly something feels off and we are forced to respond through limited improvisations that reveal our social location as well as that of others. These are the times, particularly in an academic or research setting, where we can truly examine our approach to knowledge, learning, and conducting research. Ultimately, this information about ourselves can potentially help us compensate for our limitations due to our privileges, or turn our feelings of marginality into sites for theorizing.

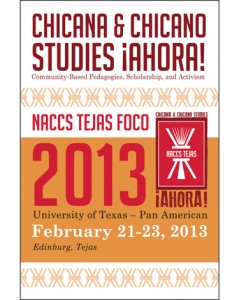

This first post will contain one example of a time I have felt “out of my habitus” and forced to deal with my discomfort and conduct myself in a way that helped me grow instead of responding in a way that legitimized only my “expert” version of the social world. Recently, I attended the National Association of Chicano/Chicana Studies regional conference at UT Pan American in Edinburg, Texas. During this conference, I attended a workshop that  taught us to link the knowledge we have gained from our parents and grandparents to the way we approach education in our current position. Most of the over 20 people participating in the workshop were first generation college students, all of them were Chicana/o, and most of them were female. All had immigrated to the United States while they were still young and the ones who had been here for a few generations had been marginalized because of their race, gender and class while attending school. Many had parents who were farm workers or low-wage workers. As I filled in the questions that were part of the exercise, I realized I am probably a 5th generation college graduate, I attended private school in San Salvador (El Salvador), and came to the United States over 9 years ago to pursue higher education.

taught us to link the knowledge we have gained from our parents and grandparents to the way we approach education in our current position. Most of the over 20 people participating in the workshop were first generation college students, all of them were Chicana/o, and most of them were female. All had immigrated to the United States while they were still young and the ones who had been here for a few generations had been marginalized because of their race, gender and class while attending school. Many had parents who were farm workers or low-wage workers. As I filled in the questions that were part of the exercise, I realized I am probably a 5th generation college graduate, I attended private school in San Salvador (El Salvador), and came to the United States over 9 years ago to pursue higher education.

I was definitely “out of my habitus” during this exercise, and I felt irked. I had a hard time really making sense of why I felt out of place, or why I felt bothered. However, this discomfort was an opportunity for me to engage with my privileges and be very mindful of my manners (including the way I looked/dressed, my language, my accent, my responses, my body language, etc.). After hearing someone talk about how they felt like their family was jealous or angry because she was pursuing a higher education (calling her white-washed and insinuating that she looked down on them), I thought about the costs to entering higher education, as a student and as a researcher. The costs for the people in this workshop (true of me as well) involve entering a new habitus and learning or adopting new mannerisms and dispositions to survive a competitive, middle-class, heteronormative and in many ways white supremacist (colonizing) environment. These mannerisms shine through in our way of speaking and writing, in the way we relate to others, in the way we assign importance to academic matters, and in the way we distance ourselves from whatever image of “bad” student we have.

In a country where students tend to be labeled as “bad” when they don’t give school as much importance as we do, where having an accent or not speaking the right version of English marks people as deviant students, and where the students who are marked the most often as “bad” students embody a particular look and mannerisms (Urrieta Jr., 2009; Valenzuela, 1999; Yosso, 2005; Yosso, Smith, Ceja, & Solorzano, 2009), then adopting the manners and dispositions of “good” students inevitably results in coming off as pretentious (as Bourdieu describes the petit bourgeoisie). Moreover, being successful in education demands that we participate in a process that distinguishes between the “good” and the “bad” students, a process of hierarchization characterized in some ways by our behavior (which I have heard undergrads at UT talk about it as “white-washing,” telling girls they’re acting too much like men, Mexican Americans telling other Mexican Americans that they’re acting “too Mexican,” or labeling certain students as disingenuous or pretentious).

Thus, being out of my habitus made me be mindful of how I was coming across to the people in that workshop. While I was irked, I decided to really listen to what was going on, and this allowed me to make a connection between the process of schooling and how my position as a researcher is mired with pretentions and manners that can be and often are marginalizing to others. Similar to (though not fully alike) the way one of the participants expressed discomfort with the way her family and friends thought she was pretentious because she was getting a college degree, my “credentials” and manners can result in research participants feeling marginalized or looked down on. Being conscious of this is one way to: (a) not blame the people I interact with for being hostile or unsupportive in my research projects; and (b) find ways to prevent myself as much as I can from marginalizing research participants and other people around me.

References:

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York, NY: Zed Books.

Urrieta Jr., L. (2009). Working from Within: Chicana and Chicano Activist Educators in Whitestream Schools. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive Schooling: U.S. Mexican Youth and the Politics of Caring. Albany, NY: State Univ of New York Press.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. doi:10.1080/1361332052000341006

Yosso, T. J., Smith, W. A., Ceja, M., & Solorzano, D. G. (2009). Critical Race Theory, Racial Microaggressions, and Campus Racial Climate for Latina/o Undergraduates. Harvard Educational Review, 79(4), 659–690.

Juan was born and raised in San Salvador, El Salvador. He has a BBA in marketing from UT Austin, and a Master’s in Women’s and Gender Studies from UT Austin. His research interests include Chicana feminisms, anti-colonial methodologies, Mexican American / Latina college students’ experiences, and Latinas and the media.

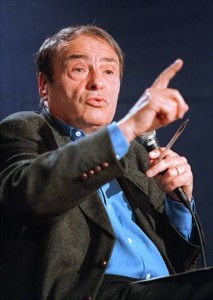

Dr. Sheldon Ekland-Olson Is 2013 Outstanding Graduate Adviser

Dr. Sheldon Ekland-Olson received the 2013 Outstanding Graduate Adviser Award.

The Graduate School Outstanding Graduate Adviser Award annually recognizes the exemplary service of one graduate adviser. Graduate advisers provide an invaluable service to the University and its community of students, faculty and staff, and this award is an opportunity to recognize these individuals.

The award includes a $3000 prize, which is presented at the Graduate School/University Co-op Awards Banquet in the spring.

Way to go, Sheldon!

Signature Course Class Gives Away $100,000

What would you do if you were handed $100,000 to give to charity? Where would you start? How would you research which organizations were most deserving or would use the money in the best way?

Last semester, students in a signature course called Philanthropy: The Power of Giving had that opportunity thanks to $100,000 from an anonymous foundation that wants to do good simultaneously in two ways: give to charity and help students learn the ways of generosity.

The course, led by Pamela Paxton of the Department of Sociology and the Population Research Center in the College of Liberal Arts, explores the history and current state of American giving and volunteering, American giving in comparative perspective, the causes and consequences of philanthropy and how to evaluate charitable programs. At the end of the course the students decide, on their own, how best to use the money. Paxton explains that she “focused on how to evaluate charities, and how to evaluate when charities are effective in their programming, because some charities are effective and some are not.”

“I think going forward, they will probably not view charitable giving in the same way,” Paxton says. “I think they may view themselves now as a resource to their friends and their families, that they’re someone who knows about what questions to ask or how to even think about where money should go.”

Paul Woodruff, inaugural dean of the School of Undergraduate Studies, taught a similar class in the spring of 2012. The Art of Giving also centered around giving away $100,000 to the charity or charities that students determined were most deserving.

Go to the UT Know feature here.

Courtesy of Mystie Pineda and Susie Cansler, Texas Student Television.

Sociology’s new home in CLA sustainable in many ways

The College of Liberal Arts building (CLA) which we now call home has been lauded as smart and environmentally sustainable. The COLA blog, Life and Letters features a great slide show emphasizing the sleek, modern design that has brought the Sociology Department and the Population Research Center together for the first time:

According to David Ochsner’s article in the College of Liberal Arts News page:

Not only is the building the newest landmark for the campus, it is also a model for innovative funding and cost-effective planning and design. The building was paid for by the college — a first at The University of Texas at Austin — which means it was built without tapping legislative or UT System funding. Although final calculations are still pending, the total cost is projected to be $87 million, less than the project’s initial expected cost of $100 million. The model is one of the reasons the resulting facility was completed under budget and with more usable space – about 16,000 square feet more – than originally planned. More about financing.

“Many new buildings today are described as innovative, but this building truly stands out as a model for cost-effective planning and design in the 21st century,” says Randy Diehl, dean of the College of Liberal Arts. “This space will be vital in our ongoing efforts to attract and recruit the highest-quality faculty and students.”

While UT Austin Sociology is known for its amazingly productive and collaborative community of scholars I think we can agree with Dean Diehl when he says:

“This is our shot at greatness,” Dean Randy L. Diehl says of the building’s potential to help attract top graduate students, faculty and grants. “A modern Liberal Arts building will ensure that we have the space we need to teach our students, promote world-class research and foster the collaboration and intellectual give-and-take that’s vital to a great university.”

It will be a pleasure to host our recruiting events in our new space, acknowledging the advent of the 21st Century in style.

Tips on maintaining health work/life balance for end of semester and holidays

From Sociology Graduate Students, Faculty and Staff:

When I am confronted with a difficult task or an academic challenge that seems insurmountable, it really helps me to think of all the previous objectives that I achieved that seemed impossible at the time.

Daily exercise first thing in the morning at least an hour of it.

My best tip, for perfectionists:

The best paper is a done paper.

My second best tip:

Nothing is more important than exercise and eating.

My biggest suggestion is to get enough sleep, especially before exams. Making time for sleep is as important as reviewing your notes and way more important than checking Facebook. If you have time for social media, you have time for sleep.

Give random grades according to the sounding of students’ last names

Answer all students’ mails with a poem

Stop checking email after 11 AM

Quit reading sociology texts-articles (I stopped doing that a while ago anyway)

Invite graduate students to drink and drink and drink

Drink with spouse

Drink alone

Taking Comps in October, and only having pass/fail classes definitely makes for a healthier end of semester 🙂

Take walks, breathe and use all your senses to feel alive. Hum, sing or dance when the mood strikes. Take time to be alone, quiet and open every day and get away for a day or two by yourself every season, if possible.

Cross dress every Wednesday at 9 pm.

Nothing like a cold beer in your hand and a warm dog at your feet to put things in perspective

Believe me, you don’t want my tips!!!!

Stop in the middle of the day and make sure you have a proper lunch. Also, go outside even if for 10 minutes. Repeat the mantra: there is light at the end of this tunnel!

Therapy

The truth is what keeps me sane during the holiday break is doing something I’ve never done before. The holiday break (exams, papers, dissertation chapters, grants) can get SO hectic. And people always seem to be forcing smiles on your face because it’s a cheerful time of year. Why not turn that forced smile into an actual real dazzling smile by trying something new? For example, I am running a 5K on Saturday and I’m taking burlesque and pole dancing classes everyday for the entire months of December and January. Though I’ve got tons of stuff to do, I’m always really excited about the next day and the new spin, grip, or twirl I’m going to learn in class. That way I come to school with a smile even when students drive me crazy!

Refuse to take your profession seriously, ask your colleagues provocative questions like: Can “hot” and “demography” can be used in the same sentence? Propose a panel: “Carnal Accounting. On the libidinal vagaries of an emerging sizzling profession.”

Tip for Staying Healthy:

1. This time of the semester invariably involves early mornings and late nights. With Texas being such a temperamental state in terms of the weather, it’s important to be prepared for any and all weather conditions. Check the weather before you go out: a sunny morning could easily turn into a chilly evening, and exposure to large temperature changes are an easy way to get sick. Whether on campus or at a coffeehouse, make sure you have the proper clothes to stay warm.

2. In an ideal world, you would be able to finish the semester while still making yourself nutritious and delicious foods in the comfort of your own home. Unfortunately – and in the “department of things you already knew”, especially if you’re a sociologist – this is not an ideal world. However, still make an effort to eat healthy by avoiding heavy amounts of fried or fast food. Make that extra effort to incorporate fruits and vegetables into your diet by packing them as snacks. Try to snack healthily and often while you study so you can avoid both the binge of fast or processed foods when you’re absolutely starving as well as the “food coma” that may come after a big meal (which will be sure to put a cramp in your productivity)

Tips for maintaining sanity:

1. Make small goals that you can meet on a daily or weekly basis. Parcel out your big projects so they don’t seem so big.

2. Solidarity! Everyone feels the crunch of the end of the semester, from the neophyte freshman to the overworked graduate student to the harried professor. Lean on your fellow academics, and let them lean on you as well. Misery indeed DOES love company.

3. Own a pet! Not only are they endless sources of affection and adoration, but consider this: your pet does not care HOW you did on that exam nor does he care if you met the deadline for NSF funding. They love you regardless.

4. And on a related note, remember: the anxiety and stress you feel is self-produced and socially constructed. We put expectations on ourselves (often deriving from social expectations, or expectations others have of us), internalize these expectations, and then discipline ourselves when we fail to meet these. That’s all well and good to a point, but it’s equally important to give yourself self-compassion. Your grades, your funding, your publication count: these things do not affect or reflect the quality of person you are or your worth as a human being.

Sit in the sun. Hug a cat. Go for long walks. Bake. 🙂

I am glad to study here. People are friendly to international students. I learn a lot not only from classes but also from people I meet.

I still struggle for English. I did not do well as I expect this semester. However, I keep trying. I think it will get better. I often take a walk alone. I love autumn here. Immersing in sunshine and beautiful nature helps to release depression. I also like to jog, which helps to refresh my brain.

Beyond the lots of great and helpful things listed below, a couple of others:

Spend time with people not in academia.

Talk about something totally unrelated to sociology with your friends. If this is hard for you, play board games or darts at a bar.

Make the bed every day. An uncluttered room is an uncluttered mind.

My tip is to listen to 90s music.

Eat Clementines. Take a three-minute dance party break to your favorite song. Do yoga. Don’t sacrifice sleep. Spend time with people who make you grin. Study near a window. Remember that our work always gets done, and that school is only one part of what defines us as human beings. Reflect upon and revel in what makes your life wonderful!

Opening the Blinds: A Convesation with Juan Portillo

In the final part of our series looking at the “Opening the Blinds” panel – dealing with the experiences of students of color here at UT and previously highlighted here and here – we offer a conversation between Juan Portillo, organizer of the panel, and Amias Maldonado, blog editor and fellow scholar of gender and critical race theory.

What was your reason for organizing this conference in the first place?

Lately I had noticed events happening this semester that may not be new but that students were definitely reacting to. I’m thinking of everything from the bleach bombings and the problematic fraternity parties to the struggles of students of color on the campus at large. These ideas of micro-aggressions and the invisible ways that students become marginalized and experience marginalization worried me. I wanted to understand more about it from a professional point of view as a scholar but also from a personal point of view as someone who is a student here, someone who works with students. Someone who has gone through some of these micro-aggressions

Obviously UT has had a checkered past when it comes to issues of racial aggression macro or micro: you can still see the segregated bathrooms in the main building, you can still see the statues of Confederate nobility around the South Mall, but at the same time, it seems like there’s something new or different in the sort of ferocity or intensity of things that are going on right now.

Mm-hm

So do you see there being something new going on here in terms of the climate of the University or do you see this as ultimately part of a larger trend that we haven’t been paying attention to but has been festering in the shadows?

I think it’s a little bit of both. I mean, it’s definitely something that never stopped. I mentioned a book during the presentation called “Integrating the 40 Acres,” and that book delineates the history of integration at UT and how the issues that students face today are still the same, they’re just being played out differently; we’re no longer fighting for the right to be here, but for the right to be really included. One way that I explain it is that students of color, female students, queer students, any kind of non-normative student is tolerated, right? That’s the kind of discourse around them. These are bodies that are supposed to be tolerated on campus, but that’s not the same as integrated, or included, or having the same kind of presence as others, right?

Definitely. Sara Ahmed has this notion of institutional passing, where she talks about how in the diversity world, what’s important is for bodies to produce sameness, and insomuch as you don’t produce sameness, as you show yourself as different, that’s immediately read as threatening and racist in itself. So the responsibility is on the non-normative student to act in line with everyone else and sort of disavow or cover up their cultural heritage, their sexual orientation, etc.

And that’s something that’s been going on. This sameness denies students a voice to actually speak up against injustice that is very real. People highlighting racial bias, gender bias, class bias at UT goes against some kind of fantasy that we’ve all bought into that everybody should be the same and that everybody is the same and that if we just don’t talk about the differences, marginalization will go away.

I think another important part of the panel and your work is the role of space. A lot of times people think about race or gender as attached to bodies, you know, but it’s really not just on bodies, it’s also in matters of space, so I was wondering if you could talk a little about that, about how space can become raced and gendered.

So most of my ideas about space and the way space is gendered and racialized came from Nirwal Puwar’s Space Invaders. Just listening to students of color or female students in male dominated fields like engineering and their experiences in the class – what they feel, how they feel, what people tell them – kind of uncovers or untangles all these forces of oppression that are still around.

So just to be clear for the non-critical race scholars out there, when we’re saying that the University is a white male space, what do we mean by that?

First of all, those bodies were inhabiting the space. It’s kind of a philosophical tradition to think that knowledge is disembodied. But in fact, knowledge happens through experience, through the person who is writing the book, through the lecturer talking to his class. So this space physically was reserved mostly for white male bodies from the inception of the University. They were creating knowledge and in doing so, they defined what counts as “real” knowledge. And this tradition carried on until finally it was challenged to include other bodies. Black bodies, female bodies, queer bodies, disabled bodies. And their inclusion transgressed this boundary that was set up around the University space. The only real bearers of knowledge were the white male bodies, but now we have women and people of color here and that crates an anxiety over who has the right to say what counts as the real truth. It’s a challenge to authority and to the authorship of knowledge.

I want to go back to the importance of privilege real quick. To me, when you’re an ally for racial or social or sexual justice, it’s not that you will always say the right thing or you will always recognize your privilege but that you have to be open to interrogating yourself and interrogating the ways in which your own assumptions are informed by your privilege and be willing to critically analyze yourself. I think there’s a lot of tension around that for allies who believe in social justice that they want to sort of “cleanse themselves” of their complicity in these structures but the fact is, you can’t cleanse yourself. You just have to be open to recognizing your privilege. Would you agree with that?

Yeah, I think one of the things that we wanted to also spotlight in the panel was that it’s important to turn the lens around on yourself. And whether you’re a researcher or not, we’re usually very comfortable analyzing others or analyzing situations as though we were not in it. But starting to understand how we are part of these institutions will have large repercussions on how we shape our institutions and communities.

So talking about tackling oppression in the institution, one of the things I was struck by in the talk was how the women on the panel navigated their relationship to the University. In a class recently, we read a book about Black Panther Party health care initiatives. One of the things that they struggled with was this tension between wanting the legitimacy that came with federal funding and the desire to maintain a critical perspective on the medical-industrial complex as a whole. In the talk, you saw these same kinds of dialogues occurring within La Collectiva Feminil. They want to critique UT as an institution but at the same time there are some things to be gained by being part of the institution, so I wondered if you could speak to that tension of being a critic and being a revolutionary from the outside on the institution but at the same time wanting to sort of use institutional structure to create change from within as well.

Well, the way I’ve heard a lot of people talk about this idea that to be revolutionary, you have to kind of oppose the institution. That once you become part of the institution you stop being revolutionary. That does explain part of it, but I feel that at a deeper level, what the panel exposed was that their resistance to being institutionalized is also an effort to maintain a particular consciousness. These are students coming from an experience that is way outside what we think the mainstream student would be or the mainstream professor would be. It’s almost like inhabiting a different dimension if that makes sense.

It does.

These are women who identify as, or have created, a queer feminine space. Most of them are first generation college students. So I think there’s hope there in the sense that – and I can’t even begin to describe exactly what I think they’re doing and what I think their goals are because I haven’t had that experience – but I just know that they have something very special going on that necessitates further analysis with theories created in the margins.

Yeah. Because there’s also another tension at work here that activist organizations have. This one is between wanting to change the system on a larger level but also for the members of that group, just wanting to have livable lives and to have that space to practice self-help, self-health, and to have a community that you can call your own without having to compromise. And that takes priority sometimes over these larger institutional issues because ultimately they’re just students that are trying to get through college.

But I think both structures can co-exist as long as we don’t try to impose a particular definition of what they are right now and what they should be if they become part of the institution. They have a space and a consciousness through the members of that group that’s fluid, that recognizes – that thrives, actually – in ambivalence. Their very survival depends on embracing ambivalence which is something that UT as an institution doesn’t necessarily do. But UT doesn’t have to understand it to be able to work with the students. They don’t have to submit to all the rules to still work with UT and still be a positive influence at UT.

So what was the experience of the panel that you organized? What did they think about the experience, what did they say to you afterwards?

They were extremely happy. They felt like somebody listened to them, I think that was the main thing. That somebody was listening. I felt the same way. That somebody is listening and that transformations can happen. The fact that the panel was composed of a mixture of undergraduate and graduates students and a staff member of UT showed how we can have an intellectual and rigorous conversation that doesn’t have to be structured in a rigid academic way.

Good point.

So not just what we said, but how we said it and how the audience responded made all of us extremely, extremely happy. Even the audience members came to me later and they were like, “We never thought that these conversations could happen in this room, in this building, in this department.” But as far as the panelists go, they were very…..it was almost therapeutic in a way. It was a way to reconstitute themselves as human beings.

Yeah, totally. And it was great in the audience to see that it was just as diverse as the panel. There were undergraduates, there were graduate students, there were professors like that lady in the back…

Yeah!

Who gave that amazing and troubling historical perspective on women of color faculty at UT. You don’t expect that kind of critical voice coming from an older white woman, but there she is. That’s an ally that if you just saw her passing in the hall, you would never know that you had that ally there. I also saw a man I know that does diversity work for the Division of Housing and Food at UT, so it speaks to the idea that there was a hunger and a need to sort of address the silence around these sorts of issues.

Yeah, and the panelists definitely want to do more. Whether it’s just us talking about what happened and what to do next or whether it’s a new conversation entirely. And I know that here in the department, we also want to do more. Just follow this format – a format that’s more fluid, that can address different issues, different interests. There’s definitely some momentum here that we can take advantage of.

Christine Williams featured on KEYE

Wal-Mart Employees Prepare To Walk Out On Black Friday

As Wal-Mart gears up for its Black Friday sale, some employees are preparing to walk out. But other employees we spoke with in the Austin area fear they could lose their jobs for speaking their mind. The protests are organized by “Our Wal-Mart” a national group representing Wal-Mart employees.The group has the support of The United Food and Commercial Workers International Union.

Wal-Mart employee Topaz Chambers is scheduled to work on Thanksgiving, but she wants people to know that working the holiday isn’t the only reason people are protesting. She makes $8.25 an hour and says it’s difficult to make ends meet. “I have to get personal loans just to pay my bills, so right now I’m kind of in debt, so I’m trying to pay those back. It’s really hard working here,” she says.

Christine Williams is the chair of the Sociology Department at the University of Texas and author of Inside Toy Land, a study of low wage retail work. She says many see the walk out as another attempt to unionize Wal-Mart workers. Williams says, “While there are tons of workers that are employed by Wal-Mart that would love to see a union, it’ll still be an uphill battle.”

Williams is skeptical because of Wal-Mart’s ability to fight against the formation of unions, but she does think the protests will help improve conditions. “I think by taking this job action, the workers at Wal-Mart will get more public sympathy and will get some concession so they can live a decent life on the jobs that they have,” she says.

As for Wal-Mart executives, they say they have a strict anti-retaliation policy and add that if any associates have concerns they want to hear about them and will take action. But employees like Topaz Chambers say they don’t want to take any chances and has deciding not to walk out. She says, “Eventually they’re going to find something to fire you about. I wish I had the mojo to actually do it but I’m kind of scared.”