Recently, faculty member Dr. Penny Green embarked on a research project looking at Austin’s unique music community. We sent our intrepid blog editor to find out more in this edition of “Research Q&A.”

What’s your project about?

My project looks at the Central Texas Americana music community and how it has changed since the mid 1970s when Austin declared itself the “Live Music Capitol of the World”. I’m focusing largely, though not exclusively, on these musicians’ economic positioning and quality of life, and how these have changed over time.

How did you get interested in this project?

Although I’ve enjoyed the “Austin Sound” since I was in grad school here in the 1970s and 1980s, I got interested in the Centex Americana music scene in about May of 2009. I got to know some musicians who introduced me to other musicians, and I kept hearing the same thing over and over. I kept hearing that the pay was staying the same as it had been for years and that it was getting more and more difficult to live in the Austin area. So I figured it was time to find out whether I just happened to be talking to a small handful of disgruntled musicians or if there’s a pattern.

How does this compare to other cities? I know that here in Austin, we’ve got some things like HAAM to try and help struggling musicians, but I can’t imagine that being enough.

I can’t presently answer that question in any definitive manner; it’s one of the things I’ll be looking at in the research. But there was at least one musician who told me that he and his family moved to Lafayette, LA because they get paid better for the gigs and the cost of living is considerably lower. He frequently plays in the Austin area, but Lafayette is now his home base.

Wow, that’s not good for the aforementioned “Live Music Capitol of the World” tagline. Why is that going on?

That’s what I’m trying to find out in the research.

Do you have any hypotheses?

I’m thinking that perhaps more of the bars and other venues are no longer owned by local people; perhaps they’ve gone under corporate control. There are also other things happening. Americana musicians and their audiences seem to be predominantly white; at  least that’s what I’ve observed. As the region becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, it’s possible they’re being marginalized as the Austin music scene grows more diverse. There’s also an age issue. When I go to Americana live gigs, most the people there are in their mid-thirties, or older. If you go to the Kerrville Folk Festival, for example, you’ll see a lot of gray hair. If the population of Austin is getting younger, then that could be contributing to the marginalization process. By the same token, we know that Austin, and perhaps much of Central Texas, is a beacon for retiring Baby Boomers; the size of the 65+ population has definitely increased over the last 10 years. I haven’t had a chance to systematically analyze the numbers to see what’s happening to the age structure of the population. And don’t forget about widening income inequality. One of its most problematic consequences is an increase in the cost of living, especially the cost of housing; widening inequality is inflationary. That’s definitely hitting musicians hard. Another component of widening inequality is wage stagnation for most people, except those at the very top. What appears to be happening to Americana musicians may be a special case of this more general phenomenon.

least that’s what I’ve observed. As the region becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, it’s possible they’re being marginalized as the Austin music scene grows more diverse. There’s also an age issue. When I go to Americana live gigs, most the people there are in their mid-thirties, or older. If you go to the Kerrville Folk Festival, for example, you’ll see a lot of gray hair. If the population of Austin is getting younger, then that could be contributing to the marginalization process. By the same token, we know that Austin, and perhaps much of Central Texas, is a beacon for retiring Baby Boomers; the size of the 65+ population has definitely increased over the last 10 years. I haven’t had a chance to systematically analyze the numbers to see what’s happening to the age structure of the population. And don’t forget about widening income inequality. One of its most problematic consequences is an increase in the cost of living, especially the cost of housing; widening inequality is inflationary. That’s definitely hitting musicians hard. Another component of widening inequality is wage stagnation for most people, except those at the very top. What appears to be happening to Americana musicians may be a special case of this more general phenomenon.

For someone who’s not familiar with the genre, how would you define Americana?

Well, that’s one of the questions we’re asking the musicians. [laughs] But my understanding is that Americana is a mixture of bluegrass, country western, blues, some jazz, and gospel….there’s a heavy emphasis in Americana on lyrics. This is not “ear candy”. It seems to appeal to an older, more mature audience. It’s a more serious kind of music.

So it’s kind of building off that folk tradition of political and social activism in the lyrics?

So it’s kind of building off that folk tradition of political and social activism in the lyrics?

You can definitely pick up an undercurrent of activist themes in some of the music, but not all.

What places in Austin can you still find this music?

In Austin, you can find Americana at the Cactus Café and Threadgill’s. You can find it at the Continental Club and the Broken Spoke. You can find it at Waterloo Icehouse. Looking at Central Texas more broadly, you can find it at Poodie’s  Roadhouse out Highway 71 west, Hondo’s in Fredericksburg, River City Bar and Grill in Marble Falls, and the Badu House in Llano. There are Americana venues in San Marcos and New Braunfels. And, of course, you can hear it in Luckenbach. Americana musicians also play a lot of house concerts.

Roadhouse out Highway 71 west, Hondo’s in Fredericksburg, River City Bar and Grill in Marble Falls, and the Badu House in Llano. There are Americana venues in San Marcos and New Braunfels. And, of course, you can hear it in Luckenbach. Americana musicians also play a lot of house concerts.

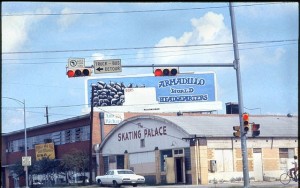

And if we think back 20 years ago, we would find more of this kind of music happening within Austin at places like the Armadillo World Headquarters or Threadgill’s…

The Armadillo and Threadgill’s on North Lamar are two key venues where the “Austin Sound” was born in the early to mid-1970s. Unfortunately, the Armadillo was torn down and replaced by a city building, I think in the early 1980s. But as I mentioned previously, you can still hear really good Americana at Threadgill’s, both north and south.

But a lot of the downtown, central Austin action has been taken over by other music whether that be for business, cultural, or demographic reasons, as you said earlier.

That’s what I suspect, but I don’t know for sure yet.

And how are you going to know “for sure”? What’s your methodological strategy?

I’ll be doing a number of things. First of all, I’m conducting interviews with Central Texas Americana musicians, using snowball sampling. I’m also looking at demographic changes that have occurred in an 11-13 county region around Austin, as well as income inequality data for those counties. I want to see how the distribution of income and cost of living have changed over time. I also want to interview other members of the music business: producers, maybe some members of the Austin Music Commission and probably some venue owners. But I haven’t gotten that far yet.

I see that you have a guitar here in your office. Do you play as well?

I played as a kid; and now I’m taking lessons from Tommy Byrd, a very talented singer-songwriter here in Austin. Debbie Rothschild, who is a very talented Americana singer/musician, has also been helping me. I’m thoroughly enjoying myself. I’m also trying my hand at songwriting. I want to immerse myself, as much as time permits (laugh), into the community that I’m studying. One thing I’ve already learned is that, when you hold a full time job, as many musicians do, it’s real hard to find time to work on your music. I look forward to continuing my work on this project.

Excellent!