by Andrew Krebs

Just over two years ago, on February 26, 2012, Trayvon Martin was shot and killed by George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida. Zimmerman, a 28-year-old mixed-race Latino man, did not deny killing Martin, a 17-year-old black teen, but claimed he had shot Martin in self-defense. Along with at least 20 other states, Florida has a “Stand Your Ground” law, which says that a person may use deadly force if they perceive they are at risk of great bodily harm in a confrontation. Although Zimmerman’s attorneys did not invoke “Stand Your Ground,” which would have given Zimmerman immunity from prosecution, the judge was required by law to read the “Stand Your Ground” provisions into the jury instructions. This was a key issue in the case because Zimmerman had identified, pursued, and confronted Martin as a threat.

Ultimately, George Zimmerman was acquitted on charges of murder in the second degree and manslaughter. To many, the verdict was a great injustice, but not necessarily a surprise. Moreover, the verdict reinforced the historically violent and oppressive notion that the life of young black men in the United States is inconsequential at best.

What does justice for Trayvon look like? Does it come in the form of a second-degree murder conviction? Does it come in the form of a long prison sentence? Or is it something else altogether?

About nine months after the untimely death of Trayvon Martin, another black teen was shot and killed by a grown man in Florida. On November 23rd, 2012, Michael Dunn, a 45-year-old white man, murdered 17-year-old Jordan Davis. Davis was sitting in the front passenger seat of his friend’s car when Michael Dunn opened fire into the vehicle. For Dunn, Davis posed a threat. But Davis didn’t have a shotgun, he was merely “riding shotgun.” Regardless, what do grown men in Florida do when they feel threatened by black teenagers? Answer: they shoot and kill them.

Similar to Zimmerman’s case, the judge presiding over Dunn’s case read the “Stand Your Ground” provisions into the jury instructions. Dunn was tried and convicted on three counts of attempted second-degree murder for the three other people in the car who survived Dunn’s assault. However, the jury failed to convict Dunn of murder in the first degree for the killing of Jordan Davis. So even though Dunn will spend the rest of his life in prison for attempting to kill Davis’ friends, no one will be held criminally accountable for the loss of Davis’ life.

So I ask you again, what does justice for Jordan look like? Does justice come in the form of a first-degree murder conviction? Does justice come in the form of a long prison sentence? Or is it something else altogether?

Some people will look at these two cases and conclude that there is no justice for young black men in America. And they are right, but not for the obvious reason. George Zimmerman was not held criminally accountable for the death of Trayvon Martin, and Michael Dunn was not held criminally accountable for the death of Jordan Davis. But I wonder, had Zimmerman and Dunn been found guilty of murder would young black men be any safer as a result?

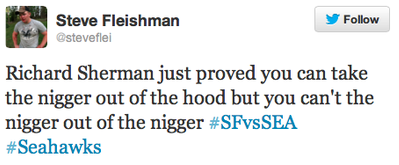

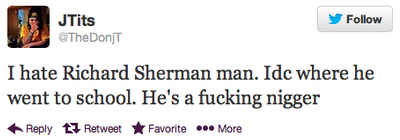

Is justice about prison sentences or is justice about bringing respect and closure? Those are two different questions, although navigating victim ideology is not easy and deference should always be given to self-determination. Still, we have to be open to the idea that prisons may not be able to solve the issue we have in this country with regards to the perceived value of a black man’s life. As Mariame Kaba suggests, “We must consider other models perhaps based on transformative justice instead of our current failed system of punitive and retributive justice.” These cases highlight the racist assumption that young black men in America need to be watched, told what to do, and surveilled.

We cannot seem to realize that violence is a result of hierarchical structures and institutions that pit people and groups against each other. We live in a country where justice is adversarial, and does nothing to promote actual understanding. In our everyday interactions, people assume disrespect. We live in a world where a black man’s innocence must be qualified (and contested).

Both Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis would be 19 years old by now. They would both be eligible to vote. They would both be eligible to serve on juries. They would both be rights-holding citizens of the United States of America. But, as young black men, they would still be subject to violence, assault, and discrimination. As a nation, we cannot seem to figure out the answer to the question: what does justice for black youth look like?