Last week, UT-Austin had the honor of hosting Dr. Michael Omi, Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of California Berkeley. Organized by the Department of Asian American Studies and co-sponsored by a number of other departments and center, Dr. Omi’s visit included a roundtable discussion with five UT faculty members from American Studies, Anthropology, History; an evening talk; and an informal lunch with graduate students. During these events, discussion not only returned to the significance of racial formation theory in the U.S.-based scholarship of race and ethnicity, but also examined the potential for these theories to examine both the durability and flexibility of “race” within global contexts. We invited sociology graduate students Vivian Shaw, Amina Zarrugh, and Christine Wheatley to share their reflections on these stimulating talks.

Vivian Shaw:

In his evening talk, Dr. Omi focused specific attention on how Asian Americans, as a socially constructed “group,” are located within a number of racial paradoxes. He unseated several ideological myths around “Asianness” and emphasized how Asian Americans have been stratified simultaneously within a white-black racial binary and relationally to other minority groups. Of particular interest to Omi was the “whitening hypothesis,” a sociological theory suggesting that high achievements around education and income and high rates of “outmarriage” experienced by many East Asian Americans might suggest a socioeconomic integration with white Americans. In asking what it means to suggest that Asian Americans are now being “whitened,” Omi argued that we interrogate what it means to develop a framework of racial analysis that assumes the stability of the category of whiteness and equates progress with the expansion of “more others” into the folds of white respectability. To what extent does such a paradigm demonstrate an investment in the privileges of whiteness?

Throughout his visit, Omi drew connections between the complex political meanings of Asians Americans in the U.S. and the production of knowledge about race within the politicized spaces of academia. He seemed to favor an anecdote dating from the publication of “Racial Formation in the United States”: he and Howard Winant (the book’s co-author)  were both surprised and disappointed when they found the book had barely made a ripple within the social sciences, but was instead taken more seriously within the humanities and legal studies. Admittedly, Omi’s criticism of the marginalization of race and ethnic studies within intellectual institutions found some coaxing from his anxious audience. Many faculty and graduate students attending the talks expressed concerns about an undeniable slashing of resources for ethnic studies not only within academia at large, but quite acutely at UT-Austin. Among a variety of measures, targeted cuts have occurred in the form of low rates of tenure for faculty of color and eliminated funding for program support staff. Over sandwiches, Omi offered advice to an intent room of graduate students worried about the implications of such cuts on critical research and their own futures within universities.

were both surprised and disappointed when they found the book had barely made a ripple within the social sciences, but was instead taken more seriously within the humanities and legal studies. Admittedly, Omi’s criticism of the marginalization of race and ethnic studies within intellectual institutions found some coaxing from his anxious audience. Many faculty and graduate students attending the talks expressed concerns about an undeniable slashing of resources for ethnic studies not only within academia at large, but quite acutely at UT-Austin. Among a variety of measures, targeted cuts have occurred in the form of low rates of tenure for faculty of color and eliminated funding for program support staff. Over sandwiches, Omi offered advice to an intent room of graduate students worried about the implications of such cuts on critical research and their own futures within universities.

In his critique of the racial politics pervasive within academic institutions, Omi offered some alternatives. He talked of his collaborative work with anti-racist community-based organizations and their efforts to “translate” academic ideas into policy-friendly language. Moreover, Omi celebrated the creative applications of racial formation theory that he has witnessed since the book’s publication and the innovative ways in which research on race and ethnicities continue to grow. Dr. Omi’s visit served as a powerful reminder of both what is politically, socially, and intellectually at stake when institutions of whiteness go unchallenged and the creative potentials for anti-racist scholarship.

Amina Zarrugh & Christine Wheatley:

In his evening lecture, Michael Omi discussed the relationship of Asian Americans to whiteness, the instability of which is nevertheless symptomatic of a persistent racial hierarchy. Asian Americans are often exalted as the “model minority” given their disproportionately high education and income levels relative to other ethnic minorities and to whites more generally. Historically, Asian Americans have always been situated against a landscape of U.S. black/white relations but are assigned to different sides of the color line at particular moments. Omi underlined the ways by which, compared to other racial and ethnic groups, Asian Americans are especially vulnerable to a racial repositioning during hostile and tense political climates. From the Chinese Exclusion Act in the early 1880s to internment camps for the Japanese during World War II and contemporary virulent discourse regarding economic threats to the U.S. posed by China, examples of the contingent position of the group in the American racial hierarchy abound. This ambivalence is further underscored by recent examples that illustrate an enduring but increasingly politicized perception that Asian Americans are threatening to whites given the U.S. public’s collective anxieties regarding job outsourcing to South Asia, unemployment, and American performance in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields; this is exemplified further in debates about college admissions such as that of recent U.S. Supreme Court case Fisher v. University of Texas.

Of paramount significance to sociologists, particularly those studying race and ethnicity from a quantitative perspective, was Omi’s discussion of whiteness as a category. Omi proposed that the measures typically regarded by social scientists as signs of inclusion and assimilation – such as intermarriage rates – ought to be more critically regarded as an expression of the continued salience of a racial hierarchy and racialized discourse. The high levels of intermarriage between Asian American women and white men, he argued, cannot be understood solely as the transcendence of racial stereotypes or cultural difference but, rather, as their very affirmation. Cultural stereotypes about Asian American women as objects of exoticized sexual desire suggest that the gender gap in Asian American out-marriage may be intimately connected to such pernicious and problematic discourses. In this way, sociologists ought to consider more critically and creatively categories of racial and ethnic identification as well as the contested meanings associated with “indicators” of social experience, such as assimilation.

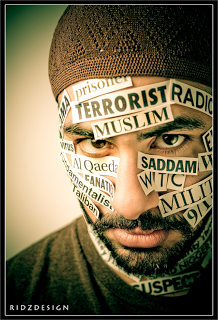

The implications of Omi and Winant’s work on racial formation and the specific case of Asian Americans are multifold. In particular, Omi places important emphasis on how moments of political tension inaugurate attendant uncertainties and processes of “Othering,” which connects to the experience of other groups seldom considered in literature on race and ethnicity in the U.S.: that of “Middle Eastern Americans.” In the

context of a post-9/11 political atmosphere, the “ArabMuslimSouthAsian” body has been racialized in specific ways (which are invariably gender-specific). Like Asian Americans, many members of these groups were historically regarded as “white.” Furthermore, and unlike Asian Americans, individuals from North Africa and the Middle East continue to officially be regarded as “white” according to the definition of the “white” category in the U.S. Census. The case of Arab and Iranian Americans parallel in many ways to that of Asian Americans yet introduces another series of questions with a different valence. A question often posed is “What does it mean to be categorized as ‘non-white’?” This case, instead, turns the question on its head to ask: “What does it mean to not be disaggregated from the category of ‘white’?” These queries and perplexities require that we interrogate not only what it means to be Asian American, Arab American, or Iranian American, but what “whiteness” means, historically and presently, in the United States.

Amina Zarrugh is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology. Her research focuses on gender, religion and nationalism in Libya.

Vivian Shaw is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology. Her research focuses on race, gender, and technology in Japan and globally.

Christine Wheatley is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology. Her research centers on processes of deportation, both as a form of exclusion and of forced return migration.