ASA Session on Visual Sociology.

ASA Session on Visual Sociology.

‘Representing Social Invisibility: Aesthetics of the Ghostly in Rebecca Belmore’s Named and Unnamed’ (Margaret Tate, The University of Texas at Austin); ‘Visual Representations of Abu Ghraib: Fashionable Torture, Gender and Images of Homoerotic Power’ (Ryan Ashley Caldwell, Soka University of America).

From Tate: During the 1980’s and 1990’s, more than 65 women went missing from the Downtown East Side area of Vancouver, British Columbia. As the poorest neighborhood in Canada, this inner city space is conceptualized within Vancouver as an unproductive space. A majority of the women who disappeared were First Nations women and thus were historically marginalized from the imaginary of Canadian citizenship. Because some were also sex workers and drug addicts, their disappearances garnered little attention from the police or from official media outlets. They had already disappeared from the respectable Canadian social body by being situated in this area. This paper analyzes a street performance by a First Nations artist named Rebecca Belmore, who was haunted by the disappearance of these women and by their invisibility as bodies that mattered. The artist produces a haunting, a concept described by Avery Gordon as “an animated state in which a repressed or unresolved social violence is making itself known” (2008, xvi). In relation to the history of colonialism in Canada, it is significant that the performance is both embodied by the artist and situated within Downtown East Side Vancouver. This paper considers problems of representation that some social events pose and suggests that Belmore’s performance rethinks representation and points to possibilities for transformational aesthetics in relation to vulnerable or marginalized subjects.

From Caldwell: Approaching society, culture, and art in a critical manner allows for the questioning of power, value, and authority—allowing for a critique of some contextual reality. Critical art allows for an evaluation of existing power structures, and an opportunity to change the world through its interpreted and exposed messages. Critical art is also a means for further informing the public about situations that are unfair, illegal, or unethical—it can give a voice to those who have been marginalized. In this piece, I analyze power in relation to gender, homoerotic torture, and the depiction of women by interpreting representations associated with the abuse at Abu Ghraib prison—from aesthetics to advertising.

Ontology, since its inception as the science of being qua being, has always been a project of division, of delimitation, of inclusion and exclusion. If the purpose of a door or gate by definition is to keep others out, then the ascent of the kingdom of being is inextricably bound up with the animals, the barbarians in the pagus beyond Athens, the demons and ghosts, and the shadows it leaves behind on the very horizon of intelligibility.

Ernest Jones saw in human symbol-making a return of the repressed under improper signifiers. It is the coded speech of the Sphinx in face of the ‘ultimate stupidity’ or dumbness [Urdummheit] of man (Cassirer). Contrary to the banal formulation, the essence of art does not lie in a ruse of technique or even a cunning of imagination (the pedestrian flash or stroke of genius), but rather in its very stupidity, its inexplicability, its futility, its silent smile amidst a clamor of injunctions to speak, to write, to paint, to think, to render visible.

Marx had said alienation is first and foremost a ‘feeling.’ But if the malaise of modernity is not our dispossession, as Marx said, by the other, but of the other, the other in ourselves, then art as the exercise of pure potential can perhaps finally open up, render sublime, those affects mercilessly suppressed and forever trailing in the torrential wake of being.

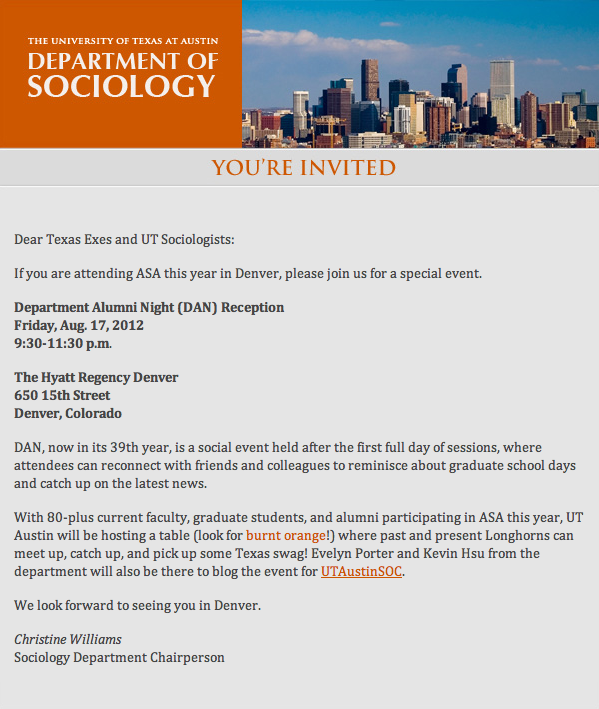

New research finds long-term marriage linked to lower alcohol consumption in men, but higher alcohol consumption in women. The study was presented at the 107th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association in Denver, CO.

New research finds long-term marriage linked to lower alcohol consumption in men, but higher alcohol consumption in women. The study was presented at the 107th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association in Denver, CO.