By Kevin Hsu

In May 1960, a high-ranking Nazi SS officer who had escaped from US custody after the war and been in hiding with his family in Buenos Aires for ten years was found and captured by agents of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad. In April the next year he was brought to trial in Jerusalem for his involvement from 1942-44 in the overseeing of the deportation of close to 500,000 Jews to ghettos and extermination camps. He was indicted on a number of charges, one of them being crimes against humanity.

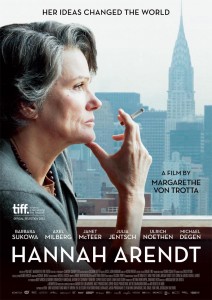

At the time, a prominent professor in the Department of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research (as it was called then), and a Jewish refugee from Germany herself, offered to travel to Jerusalem, to the very ‘Beth Hamishpath’—House of Justice (though some people say it should be more accurately translated as ‘House of Judgment’)—to cover the trial for The New Yorker, claiming it would be her last opportunity to see a major Nazi ‘in the flesh.’ Her report, published in 1963 and later as a book, engendered a great deal of controversy that led to a string of personal and professional falling-outs.

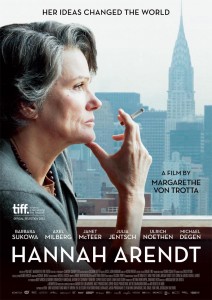

This is the subject of the movie Hannah Arendt.

I remember when I was in graduate school I went to a seminar by Margarethe von Trotta, the director of the movie. I hadn’t heard of her before. The students had just seen a new movie by Volker Schlöndorff the previous night. I didn’t think too much of it, so when I learned von Trotta had been married to him, I can’t well say I didn’t harbor some prejudices already before attending the seminar.

Actually I don’t remember much from the seminar, except von Trotta herself. Even though it was August, the weather in the Swiss Alps was cold and wet. She wore a red fringed shawl over a black linen blazer, a black turtleneck sweater, black suit pants, and flats, also black. About sixty years old, she had on dangling, gold and red coral earrings, a fountain of platinum-tinted silver hair splashing onto her shoulders, framing a squarish, lined, somewhat coarse face—razor lips, scythe nose, blue-gray eyes shining, as if with the gleam of a sword just drawn. There were a red coral bangle and thin gold bracelet on her left wrist. She had a habit of pushing the sleeves of her blazer up with her hands as she talked, like she was getting ready to dig deeply into something, and every time she did so the bangle and bracelet on her wrist clanged and clacked, stringing together a beaded curtain through which her low hoary voice would pace back and forth.

In the next three days we watched The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, The Second Awakening of Christa Klages, Marianne and Juliane, Rosa Luxemburg (the actress who played Hannah Arendt, Barbara Sukowa, was also the lead in those two movies), and Rosenstrasse, another film about the Holocaust. It was practically a crash course in New German Cinema.

Honestly I can’t say I like her movies, including Hannah Arendt. By ‘art house’ standards, they don’t stand out in terms of aesthetics or style. By Hollywood standards, there aren’t enough, if any, explosions, car chases, special effects, beautiful actors, beautiful actresses, plot twists, or product, or ‘lifestyle,’ placements. Von Trotta’s movies tend to be ‘just enough’ movies—just enough historical backdrop, just enough close-up moments, just enough plotting and intrigue, just enough presenting of different perspectives, just profound enough dialogue, just memorable enough actors, just enough music, just enough ambiguity. They cover all the bases. It’s as if she were merely ticking off a list. They are very ‘efficient’ movies. If they had a temperature, it would be 70°F—standard room temperature. In person, however, she is very likeable—affable and generous, yet straightforward and sharp. Just very genuine, real. Very 98.6°F. It’s as if her works took her warmth and coolness, poured them into the same pot and made them simply lukewarm. I like her more than her movies. Often you like somebody’s work only to be disappointed, even disgusted, when you finally see the man or woman ‘behind the candelabra’ (like Heidegger); more rarely, it seems, does who they are actually surprise you by being better, and more interesting, than what they do. If I had a choice I would definitely choose to meet and be the latter.

Hannah Arendt in the book Eichmann in Jerusalem coined the phrase ‘the banality of evil,’ about how people can depersonalize and dehumanize other people when they simply follow the rules, or ‘follow orders.’ Then all sorts of acts and atrocities can be justified and committed against a number, a statistic, an abstract entity, or something ‘unworthy,’ in the name of whatever the rules and orders serve—often ‘the Good,’ with everything ‘the Good’ is against then coming to be seen as ‘bad,’ or even ‘evil.’ Arendt attributed Eichmann’s actions and these kinds of actions in general to the perpetrators’ ‘inability to think.’ However, a lot of people, for some reason, seem to leave off what she said immediately after that—‘namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else.’

Frankly put, what Arendt is talking about is really selfishness.

Osamu Dazai in 1948 wrote a story about a woman in dire financial straits and at the end of her rope who was desperately trying to plead with a banker for help, but the banker, a model husband and father who arrived home from work punctually every day, simply told her he had to get off of work at 5 pm and to come back the next day during normal business hours. The woman, having nowhere to go, committed suicide that evening. Osamu Dazai’s conclusion was: ‘Home is the root of all evil.’

Arendt herself observed that Eichmann was an irreproachable husband, father, brother, son, and friend. But it was exactly for those closest to him and for himself that he carried out those actions. When we put our welfare, career, ‘pursuit of happiness,’ or what we think is good, and that of the people ‘inside our circle,’ above and to the exclusion of everything and everyone ‘outside our circle,’ we shut them out. Our pound of iron becomes heavier than their pound of feathers. It’s easy then to justify actions against anything in our way, and accept, even advocate, rules and ideas that support those actions, using them as shields. And no one can blame us, because we’re ‘in the right,’ or, simply, we’re just ‘playing by the rules.’

Thinking from the standpoint of somebody else doesn’t mean agreeing with them, or even trying to find agreements with them. It doesn’t mean understanding or identifying, or even empathizing with them. It means something much simpler. It just means ‘listening.’

There is a scene in the movie, where we see Arendt’s face, pensive, with brows furled, eyes squinting; a few seconds later, sounds rush in, and we realize she is listening to a news broadcast on the trial. The expression of thinking is the expression of listening.

Only when we listen, can we allow ourselves to open up. And only when we allow ourselves to open up, can we begin to think.