by Anima Adjepong

Ask any student of Sociology to name the foremost sociological theorists and you’re likely to get the same response: Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Max Weber. Scholars such as W.E.B Dubois, who conducted and wrote the first urban sociological study The Philadelphia Negro (1899), and Charles S. Johnson, whose book The Negro in Chicago (1922) provided an elevated analysis of the institutional structures of anti-black racism that led to the Chicago race riots in 1919, are rarely taught in introductory sociological theory classes, whether at the graduate or undergraduate level. Instead these scholars are read as prominent African-American scholars whose knowledge production is marginal to the sociological project.

The marginalization of scholars of color within the discipline is indicative of how the sociological canon is constructed through what philosopher Charles Mills (1997, 18) calls an epistemology of ignorance, which involves learning to “see the world wrongly, but with the assurance that this set of mistaken perceptions will be validated by white epistemic authority.” Sociologist Stephen Steinberg (2007) offers an excellent explication of how the epistemology of ignorance shapes sociological thought. Steinberg’s core argument is that sociology operates under epistemologies of ignorance and wishful thinking, which obfuscate the problems of oppression and racism. Instead these epistemologies ensure that as a discipline, we ask the wrong questions and insist on maintaining a cool distance from choosing a side on political issues.

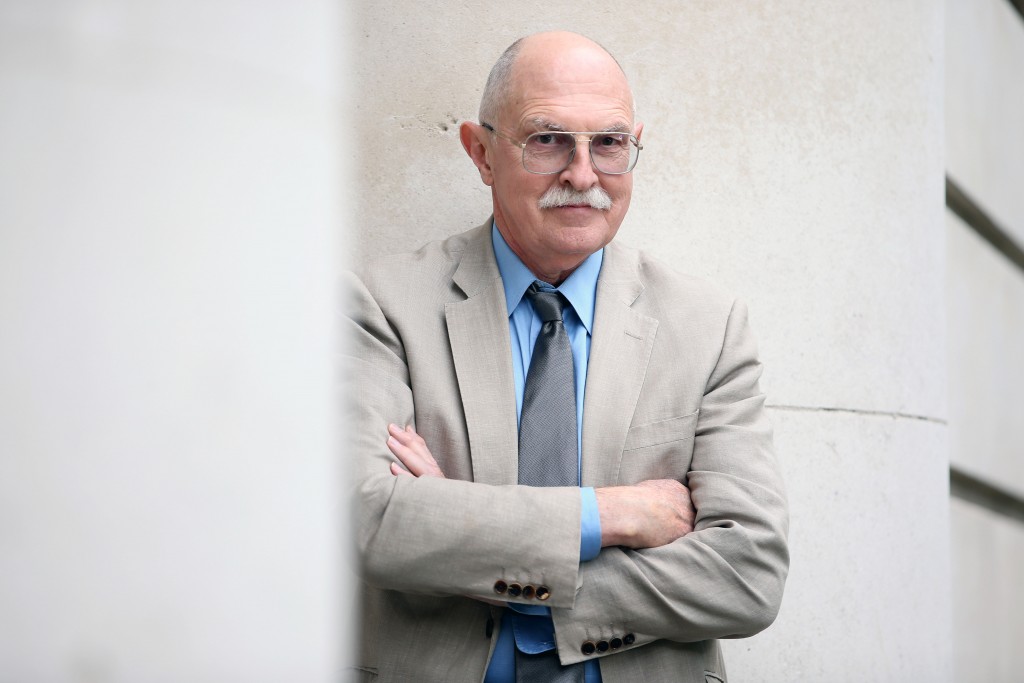

In an invited lecture organized by the Race and Ethnicity Group and sponsored by the Warfield Center and the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies, Professor Gurminder Bhambra offered an analysis of how the racialized character of sociological thought, which absents certain theorists from the construction of the discipline, hinders an understanding of race and ethnicity beyond questions of distributional inequality or identity. As scholars, our best work is the kind of work that produces insights into the normal operation of racial structures. As Vilna Bashi Treitler (2015) wrote, “[Social scientists’] work may be used either in the service of shoring up or dismantling racial systems (and there is no third option)” (160). When we fail to challenge the racialized epistemological frameworks of our discipline, we contribute to sustaining racial inequality and other forms of social justice effected through racism.

Bhambra is Professor of Sociology at the University of Warwick in the UK and currently a visiting fellow in the sociology department at Princeton University. She has written widely on historical sociology, contemporary theory and postcolonial and decolonial studies. Her first book, Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination (2007) examines how the sociological task of making sense of modernity fails to engage critically with how, through colonialism, the histories of Europe, Asia, and Africa were connected in the construction of modernity. Instead, she argues, sociological renderings of modernity are constructed through what J.M. Blaut (1993) calls telescopic history, which takes the present conditions in Europe and the West and uses these conditions to make claims about the past. Within this framework, European success has nothing to do with its exploitative economic relationships of other parts of the world.

Bhambra’s most recent book, Connected Sociologies (2014) extended this line of thought by arguing that a reliance on Europe as the epicenter of modernity fails to incorporate the ways in which colonial and postcolonial relations shape modernity. She argues for a historical sociology that incorporates a postcolonial critique, which allows us to deconstruct the ideologies and cultural frameworks that shape understandings of modern cultural, political, and social formations.

Professor Bhambra’s lecture, entitled “Disciplinary Histories and Racialized Epistemologies” further animated her arguments through a discussion of the current limitations of conventional sociology and a look towards what a departure from the dominant racialized epistemological frame might bring. Bhambra argued that by critically examining the connectedness of the sociological world through an acknowledgment of how, for example, European ideas spread through the world as a result of colonialism, imperialism, oppression, and enslavement, a different and more accurate narrative emerges. Connectedness urges us to reconsider historical connections and open up examinations from and of different perspectives. It is not simply a question about inclusion, but rather a push to critically examine and redress the sociological consequences of the erasure of certain perspectives that challenge dominant myths that surround the rise of the West and the way we understand the world today.

To return to the composition of the U.S. sociological canon and its silences regarding challenges to the racialized epistemology, I want to note a few things that Bhambra’s talk highlighted for me and that I hope our intellectual community will reflect on and practice. Firstly, it is important that our theory classes challenge the socially constructed sociological canon that relies on epistemologies of ignorance. Failing to do so is a great disservice to our students who are working hard to make sense of a world in which historical and contemporary connectedness are more explicit everyday.

Secondly, we can be more open to applying a postcolonial critique to sociological studies. This perspective opens up space to think more critically about the connectedness of contemporary and historical formations and the ways in which particular historical narratives undergird ideal type comparative models. For example, the dominant assimilation paradigm that frames immigration scholarship relies on the historical experiences of white immigrants to the United States. However, this model ignores the ways in which this paradigm excludes people of color. A postcolonial perspective considers how the historical narratives that proffer assimilation as the teleological endpoint for immigrants relies on an incomplete understanding of the social world in which the framework is constructed (for more see Spickard 2007; Pierre 2004). By taking seriously how the racialized epistemologies of our discipline hinder our understanding of key sociological tenets, and working to redress these conceptual issues (which also frame our methodologies) we can, as a discipline, produce knowledge that dismantles racial systems.

Works cited

Bashi Treitler, Vilna. (2015). Social Agency and White Supremacy in Immigration Studies. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1(1): 153-165.

Bhambra, GK. (2014). Connected sociologies. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic Press

Bhambra, GK. (2007) Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination London, UK: Palgrave.

Blaut, JM. (1993) The Colonizer’s Model of the World: Geographical Diffusionism and Eurocentric History New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Du Bois, WEB. (1899). The Philadelphia Negro: a social study (No. 14). Published for the University of Pennsylvania.

Feagin, JR. (2013). Racist America: Roots, Current Realities and Future Reparations. New York, NY: Routledge

Johnson, CS. (1922). The Negro in Chicago: A study of race relations and a race riot. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Mills, CW. (1997). The racial contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Pierre, J. (2004). Black immigrants in the United States and the” cultural narratives” of ethnicity. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 11(2), 141-170.

Spickard, P. (2007) Almost All Aliens: Immigration, Race, and Colonialism in American History and Identity. London, UK: Routledge

While efforts in the corporate world to promote gender diversity have been ongoing since the 1990s, the representation of women at higher corporate levels is still relatively poor – more than 83 percent of board directors are still male. In new research on women scientists in the oil and gas industry,

While efforts in the corporate world to promote gender diversity have been ongoing since the 1990s, the representation of women at higher corporate levels is still relatively poor – more than 83 percent of board directors are still male. In new research on women scientists in the oil and gas industry,