by Shannon Malone

I am in a profession of words. I am in a field that attempts to use words to uncover systems of power and oppression. As a child, I read the words of Mississippi activist Fannie Lou Hamer’s testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent beings, in America?” I grew up listening to the words of my grandmother back home in Mississippi, who knows all too well the cost of racially motivated violence from her long days of voter’s registration organizing in the 1960s: “We had no choice. We knew we had to push for you. Now you have no choice. Now you have to push for what is to come.”

All of these words, and yet, I feel like all too often I have none.

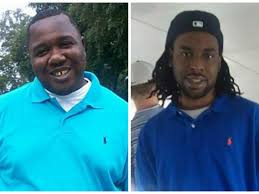

I have no words for the brutal, sensationalized deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. I have no words for the senseless murders of five police officers in Dallas following a peaceful protest for Black Lives Matter. I have even fewer words for those who behave like scavengers and quickly offer the unburied bodies of these officers as evidenced carcasses that a movement for the humanity of black people is a movement against others, offering us distractions in #bluelivesmatter or #alllivesmatter.

It’s been 60 years since the world bore witness to the gruesome death of Emmett Till and 60 years since the American justice system let his killers go free. Visit Sumner, MS and you can still see the scars of a town divided by railroad tracks and resources, a town where the Bryant and Milam family continue to hide behind their power and are rumored to threaten anyone who questions them about the death of a 14-year-old boy. Now, Philando Castile and Alton Sterling join Emmett Till, along with countless others.

Do we even know how many black bodies this country has buried? How many lay at the bottom of the Atlantic, how many lay underneath the cotton fields of the South, how many lay in the prison cemeteries, how many lay with their blood still warm on the streets? Will I join them? Will my brother? My nephew?

I was only 19 years old, headed to the mall with my girlfriend, and excited about attending a sorority party that night when I was pulled over by police for a traffic violation. Surrounded by two cops, I remember the moment he pulled out his gun and pointed it at me. I can remember him yelling at my friend and I, as we stood stunned and confused. He yelled at us to put our hands up and get back in the car, and I could not decide what to do. Everything around me slowed down. Should I keep them up, as instructed, or should I open the door and get back in the car, as instructed?

I was 19 years old when my life flashed before my eyes. Could my body be buried with the untold others and eulogized with words like, “Here lies Shannon Malone, gone, but not forgotten?”

This is the America we live in. What words help us make sense of this? What words do you use to make yourself feel better about living in a country with such a high body count? What words do you post online to signal to others that you understand? What are the words you use to tell little brown girls and boys that there is a better tomorrow?

My people have spent the last week, or more accurately the last few centuries in mourning, and I demand to know: what are your words?

There comes a time when words, while meant to show sympathy and support, are used as placeholders for action, placeholders for those comfortable enough to push the brink with their words but are not yet willing to sacrifice their bodies. Words that offer escape from the harsh reality of all the black bodies piling up around us. Words used before and after a Sean Bell or a Trayvon Martin, with yet another brown body in the ground who we lay words on like “rest in peace.” Rest in peace, but live in fear, humiliation, or violence? What words do you use to justify another life gone too quickly?

Malcolm X once said, “If you’re not ready to die for it, put the word ‘freedom’ out of your vocabulary.” My grandmother, like her grandmother before her, hummed spirituals underneath her breath when she had no more words. In a country that has a proven history of kidnapping, beating, hanging, imprisoning, and shooting black people and using words to explain, describe, predict, and reflect on our buried, black bodies, what words do you offer up?

I have none.

Shannon Malone is a PhD student in the department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on how social networks enable mobility for women and girls throughout the lifecourse. Shannon is a W.K. Kellogg Community Leadership Fellow in Mississippi where she works to help vulnerable children and their families achieve optimal health and well-being, academic achievement and financial security.