Celebrating the end of the old and the coming of the new year here in balmy Austin, TX. Happy and peaceful holidays to everyone celebrating here and elsewhere.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hvkKgeYQls

Celebrating the end of the old and the coming of the new year here in balmy Austin, TX. Happy and peaceful holidays to everyone celebrating here and elsewhere.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hvkKgeYQls

by Katherine Sobering

At a well-attended talk sponsored by the Urban Ethnography Lab, Dennis Rodgers, a professor of Urban Social and Political Research at the University of Glasgow discussed his paper, “From ‘broder’ to ‘don’: Methodological reflections on longitudinal gang research in Nicaragua, 1996-2014.”

At a well-attended talk sponsored by the Urban Ethnography Lab, Dennis Rodgers, a professor of Urban Social and Political Research at the University of Glasgow discussed his paper, “From ‘broder’ to ‘don’: Methodological reflections on longitudinal gang research in Nicaragua, 1996-2014.”

Over lunch, Professor Rodgers reflected on the academic career that began with his dissertation research in Nicaragua in the 1990s. Since this initial period of research, Professor Rodgers has returned to the specific barrio of his dissertation fieldwork seven times. And he plans to continue going back.

As his dissertation evolved into a long-term research project, Professor Rodgers conceived of it as longitudinal ethnography. By this, he refers to immersive ethnographic fieldwork conducted diachronically over an extended period of time, or through appropriately timed revisits (Burawoy 2003; Firth 1959).

But what are the implications of such on-going ethnographic research? How can we make sense of ethnographic “revisits”? And what are some of the pitfalls that may result?

Certainly one of the greatest benefits of ethnographic research is to observe dynamic social processes as they occur over time. As Professor Rodgers pointed out, he has more or less witnessed a cycle of cultural transformation through the institutional evolution of a gang in Nicaragua.

Yet the specific challenges that arise from such an endeavor are many. First, the notion of “the field” as a spatially and temporally bounded location is increasingly misleading. Professor Rodgers (and many of the event’s attendees) stay in regular contact with individuals in “the field”. Social media further complicates this artificial division.

Over the course of a lively discussion informed by many different experiences conducting ethnographic research, we critically examined the idea of a “revisit.” If “the field” is no longer a bounded place, where do you go? To the original site of study? Or do you trace the network of people you once knew? Or follow a particular trend or social phenomena?

Moreover, “the field”—may it be sites, people, or networks—changes over time. But this is not unidirectional. As ethnographers, we also change. We age. We read more. We go through life changes that may provide different perspectives on the same event. And all of this affects how we do ethnography.

Professor Rodgers clearly describes such changes in his own career. Almost ten years ago, he conducted mostly participant observation in the barrio, and was even inducted into the gang he studied (Rodgers 2007).

Today, he is treated as a respected elder (a “don”). His methodological tools increasingly rely on interviews and informal conversations with long-term informants.

The form and function of ethnographic research is changing. In his paper, Professor Rodgers understands his return visits as “serendipitous time lapse(s).” Yet it seems to me that these ethnographic revisits are institutionally structured by his academic career trajectory as well as access to funding.

Structural changes in both funding and time-to-degree requirements affect the way ethnographic research is produced. For many graduate students, multiple periods of “pre-dissertation” fieldwork pave the way for a prolonged period of dissertation-worthy immersion

Examples abound in our department alone. Marcos Pérez conducted three summers of ethnographic research with piquetero groups in Argentina before returning for a year of dissertation fieldwork. Katie Jensen has studied asylum seekers in Brazil for three summers, and is now preparing for an extended period of dissertation research. And I conducted my first period of fieldwork in Argentine worker-recovered businesses as an undergraduate in 2008, having since spent a total of nine months in the field prior to my dissertation research.

Professor Rodgers did well to remind us: “Research is by its very nature imperfect and limited, and this not only in terms of ‘’the data’, but also ‘the method’, ‘the researcher’, and ‘the context’”. Indeed, grappling with the notion of longitudinal ethnography spurred many of us to think critically about how the pattern of our fieldwork shapes what data we collect, the topics we analyze and ultimately how we interpret our findings.

References:

Burawoy, M., (2003), “Revisits: An outline of a theory of reflexive ethnography”, American Sociological Review, 68(5): 645-79.

Firth, R., (1959), Social Change in Tikopia: Re-study of a Polynesian Community after a Generation, London: George Allen & Unwin.

Rodgers, D., (2007), “Joining the gang and becoming a broder: The violence of ethnography in contemporary Nicaragua”, Bulletin of Latin American Research, 27(4): 444-61.

Rodgers, D., (Forthcoming), “From ‘broder’ to ‘don’: Methodological reflections on longitudinal gang research in Nicaragua, 1996-2014.”

by Luis Romero

One of the most important things graduate students can do while in grad school is to take as many methodology courses as possible. This advice is given to us by our mentors, faculty and older graduate students. Yet no matter how many methods classes you take, it is impossible to master every method – getting one down is difficult enough. While mastering one method lasts some researchers their entire academic lives’, others venture into different types of questions and units of analyses that warrant the use of new methods. What happens, though, when you are out of graduate school and want to change methods? How do you go about this change? Navigating the different assumptions, techniques of data collection and analysis of a new method can be overwhelming. However, it is something that can and has been done. Professors Michael Young, Néstor Rodríguez and Sheldon Ekland-Olson joined the Power, History, and Society Network (PHS) to describe how they transitioned into new methods. Each provides a piece of the puzzle to better understand how sociologists can change methods, even without prior graduate training.

Dr. Michael Young: Keeping Books on the Nightstand

Of the three panelists, Michael is the most recent to transition to a new method for a project he is currently working on. His training in graduate school was oriented toward the study of old social movements using historical sociology. Specifically, he was trained to map the trajectories of different movements to get at the causal sequence of events (e.g. how the morality and religious schemas of the evangelicals helped to mobilize them during the antebellum era). Michael has recently shifted to studying the DREAMers – a group of immigrant rights’ activists who are concerned with helping undocumented immigrants that were brought to the U.S. as children and attended school in the U.S. However, because the DREAMers and their activities are an ongoing phenomenon, Michael understood that he could not rely solely on his training in historical methods to study this group. Instead, he decided to learn about ethnographic and interviewing methods. This posed a problem for Michael, since studying an active movement followed a different logic than studying something that already had an outcome (and analyzing how and why that outcome came to be). To resolve this dilemma, Michael turned to Professors Javier Auyero and Harel Shapira and asked them both to give him a list of their favorite ethnographies. Once he obtained these lists, Michael read and studied the exemplars of ethnography, keeping these books on his nightstand for easy access so he could read them nightly. Reading these exemplary works, coupled with his interactions with the DREAMers has helped Michael transition from historical sociology to ethnography and given him new insights into the complexity of this new social movement.

Of the three panelists, Michael is the most recent to transition to a new method for a project he is currently working on. His training in graduate school was oriented toward the study of old social movements using historical sociology. Specifically, he was trained to map the trajectories of different movements to get at the causal sequence of events (e.g. how the morality and religious schemas of the evangelicals helped to mobilize them during the antebellum era). Michael has recently shifted to studying the DREAMers – a group of immigrant rights’ activists who are concerned with helping undocumented immigrants that were brought to the U.S. as children and attended school in the U.S. However, because the DREAMers and their activities are an ongoing phenomenon, Michael understood that he could not rely solely on his training in historical methods to study this group. Instead, he decided to learn about ethnographic and interviewing methods. This posed a problem for Michael, since studying an active movement followed a different logic than studying something that already had an outcome (and analyzing how and why that outcome came to be). To resolve this dilemma, Michael turned to Professors Javier Auyero and Harel Shapira and asked them both to give him a list of their favorite ethnographies. Once he obtained these lists, Michael read and studied the exemplars of ethnography, keeping these books on his nightstand for easy access so he could read them nightly. Reading these exemplary works, coupled with his interactions with the DREAMers has helped Michael transition from historical sociology to ethnography and given him new insights into the complexity of this new social movement.

Dr. Néstor Rodríguez: An Important Key Lies in Co-authorship

Néstor Rodriguez’s transition between methods took a slightly different trajectory than Michael Young’s. Michael’s was a constant transition between historical work, interviews and surveys. Nestor’s graduate work was focused on tracing the trajectory of migration in relation to capitalist growth, combining historical methods with theory building. In his post doctoral research, Néstor began studying Mayans from the Guatemalan Highlands who were migrating to Houston, Texas. It was during this project that Nestor began to incorporate fieldwork into his research. Later on, Néstor also began to use more quantitative methods – surveys and data sets- in order to study deportations. In the past year alone, he has published two articles on El Salvador using surveys, a book (coming in January 2015) that incorporates fieldwork from Guatemala and is a return to his first love of historical sociology. When asked how he was able to incorporate so many different methods, Néstor stated that an important key could be found in co-authorship. Co-authoring with other researchers that are more adept at various methods allows for the successful incorporation of those methods. Similar to Michael’s approach, Néstor also recommended that students considering a transition to new methods should read widely in sociology. That will allow them to become familiar with different sociological methods and their implicit logic.

Néstor Rodriguez’s transition between methods took a slightly different trajectory than Michael Young’s. Michael’s was a constant transition between historical work, interviews and surveys. Nestor’s graduate work was focused on tracing the trajectory of migration in relation to capitalist growth, combining historical methods with theory building. In his post doctoral research, Néstor began studying Mayans from the Guatemalan Highlands who were migrating to Houston, Texas. It was during this project that Nestor began to incorporate fieldwork into his research. Later on, Néstor also began to use more quantitative methods – surveys and data sets- in order to study deportations. In the past year alone, he has published two articles on El Salvador using surveys, a book (coming in January 2015) that incorporates fieldwork from Guatemala and is a return to his first love of historical sociology. When asked how he was able to incorporate so many different methods, Néstor stated that an important key could be found in co-authorship. Co-authoring with other researchers that are more adept at various methods allows for the successful incorporation of those methods. Similar to Michael’s approach, Néstor also recommended that students considering a transition to new methods should read widely in sociology. That will allow them to become familiar with different sociological methods and their implicit logic.

Dr. Sheldon Ekland-Olson: Delve into Different Projects

Sheldon Ekland-Olson has done research using various methods throughout his career. His earliest work was heavily quantitative and was among the first to incorporate dummy variables into the research. This was largely influenced by his math background and because he came into graduate school as a student of methods. Sheldon’s first shift occurred during his time in law school, as he finished his dissertation. During his research, he became involved in learning about the rights of those who were institutionalized, which led him to spending time in prisons. It was through this experience that Sheldon began studying Texas Prison Reform, using quantitative methods along with qualitative methods to learn about the lived experiences of the prison inmates. His most recent work on life and death decisions uses historical methods to study the boundaries of social worth when people are faced with different issues such as: abortion, neonatal care, assisted dying and capital punishment. For Sheldon, switching methods was something that was necessitated because he believes that you should let your problem determine the method that you use. Sheldon’s advice is derived from his own experience: you should delve into different projects and learn new methods by striving to answer different questions.

Sheldon Ekland-Olson has done research using various methods throughout his career. His earliest work was heavily quantitative and was among the first to incorporate dummy variables into the research. This was largely influenced by his math background and because he came into graduate school as a student of methods. Sheldon’s first shift occurred during his time in law school, as he finished his dissertation. During his research, he became involved in learning about the rights of those who were institutionalized, which led him to spending time in prisons. It was through this experience that Sheldon began studying Texas Prison Reform, using quantitative methods along with qualitative methods to learn about the lived experiences of the prison inmates. His most recent work on life and death decisions uses historical methods to study the boundaries of social worth when people are faced with different issues such as: abortion, neonatal care, assisted dying and capital punishment. For Sheldon, switching methods was something that was necessitated because he believes that you should let your problem determine the method that you use. Sheldon’s advice is derived from his own experience: you should delve into different projects and learn new methods by striving to answer different questions.

A Few Warnings about Transitioning Methods from the Panelists

by Shantel Buggs and Brandon Robinson

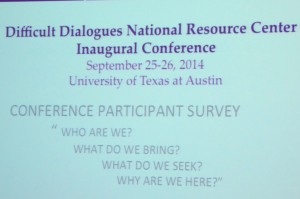

Last Friday, we had the opportunity to attend the inaugural biennial conference for the Difficult Dialogues National Resource Center (DDNRC) entitled “Advancing Meaningful Difficult Dialogues Practices in Higher Education: A New Imperative of Democracy?” The mission of the DDNRC is to advance innovative practices in higher education that promote respectful, transformative dialogue on controversial topics and complex social issues, thereby reflecting a commitment to pluralism, academic freedom, and strengthening a democratically engaged society. A central goal of this year’s conference was to propel academic communities to have productive engagements with difficult dialogues.

Last Friday, we had the opportunity to attend the inaugural biennial conference for the Difficult Dialogues National Resource Center (DDNRC) entitled “Advancing Meaningful Difficult Dialogues Practices in Higher Education: A New Imperative of Democracy?” The mission of the DDNRC is to advance innovative practices in higher education that promote respectful, transformative dialogue on controversial topics and complex social issues, thereby reflecting a commitment to pluralism, academic freedom, and strengthening a democratically engaged society. A central goal of this year’s conference was to propel academic communities to have productive engagements with difficult dialogues.

Dr. Silvia Hurtado, the opening keynote speaker, focused on the following central concern: if we are not the society that we aspire to be, how do we get there? She suggested that while “problems” are complex, we have the capacity to be change agents. However, there are prevailing norms that we must face as educators and members of academic communities: 1) people’s mindsets that they come into college with, 2) traditional notions of teaching and learning, and 3) first-years in college ask fewer questions in the classroom than they did in high school.

Hurtado emphasized that we need engaging forms of pedagogy in order to challenge these academic norms and to move students from their own embedded worldviews. One interesting pedagogical approach mentioned by Dr. Silvia Hurtado is for educators to learn that they are not the only authority in the classroom. Students are teachers as well, and peers can be an authority on a topic for one another. However, as educators, we must be good facilitators, which does not mean being neutral. It does mean that we must develop skills of active listening and embrace conflict and different voices in order to make progress. It should be noted, however, that choosing which educators get to de-center themselves as the authority in the classroom is fraught with various forms of privilege. Certain marginalized bodies are often already questioned as having authority, so this pedagogical approach may be difficult or not conducive for certain people’s classrooms. Despite this, new forms of teaching and learning outside of traditional forms of lecturing are needed in order to truly engage in difficult dialogues and to transform the mindsets of students in order to make them better global citizens.

Following the keynote, we broke out into smaller workshop groups in order to have conversations about what distinguishes a “difficult dialogue” program from a one that promotes and/or encourages “respect for difference(s).” Much of the conversation focused on the fact that difficult dialogues are not value-neutral and that it is imperative to push students and educators beyond a notion of “respect as tolerance”, instead aiming toward “real” action and social change. In thinking about what goals should be set for a difficult dialogue and how these goals could be identified or measured, some of the more interesting suggestions involved some directly observable goals (such as the ability to facilitate a dialogue in class or to identify strategies of facilitiation and demonstrate active listening). Others were more business-minded (such as measuring the numbers of department heads, faculty, and campus leadership groups that participate in difficult dialogue training) or philosophical (such as seeing a student develop a better understanding of structural oppression and inequality and/or an awareness of their positionality in the world). These workshops were a great opportunity to learn about the kinds of courses/programs going on at other schools and how they prioritized social justice within them.

The workshop groups prepared us for the interactive theater session that led to an interesting discussion about which classrooms and which professors can actually engage in difficult dialogues. The interactive skit was about four undergraduate students who had witnessed a religious demonstration and saw people praying on campus. They entered a classroom discussing religion, protests, praying, the First Amendment, and other issues that undergraduates are likely to encounter and discuss. However, the classroom was an English course, so when it was time for class to start, the professor tried to shut down the lively debate. The skit ended with the professor telling students that it was his job to teach them about dangling modifiers, and that he did not feel like religious controversies should be discussed in his classroom. This performance raised several important questions: When should professors engage in difficult dialogues with their students? Should these issues only be discussed in certain classroom settings? For example, should religion only be discussed in a religion course, but not in an English course?

The workshop groups prepared us for the interactive theater session that led to an interesting discussion about which classrooms and which professors can actually engage in difficult dialogues. The interactive skit was about four undergraduate students who had witnessed a religious demonstration and saw people praying on campus. They entered a classroom discussing religion, protests, praying, the First Amendment, and other issues that undergraduates are likely to encounter and discuss. However, the classroom was an English course, so when it was time for class to start, the professor tried to shut down the lively debate. The skit ended with the professor telling students that it was his job to teach them about dangling modifiers, and that he did not feel like religious controversies should be discussed in his classroom. This performance raised several important questions: When should professors engage in difficult dialogues with their students? Should these issues only be discussed in certain classroom settings? For example, should religion only be discussed in a religion course, but not in an English course?

During the Q&A following the theater performance, many people felt that the professor had valid concerns about addressing these issues in his classroom. Many professors worry about tenure; engaging in these difficult dialogues could create barriers to their ability to get promoted. Likewise, students may give professors bad evaluations if they begin engaging in difficult dialogues that students perceive to have nothing to do with the topic of the class. As the conversation continued, it became evident that there are structural constraints in place that make it hard for some professors to engage in difficult dialogues in the classroom or in the larger academic community. Based on the reactions of some of those present at the session, these constraints must be addressed before institutions put greater pressure on professors to do the work of trying to “change mindsets.”

Overall, we walked away from Friday’s experience with important questions to consider, some awesome books, and new theoretical lenses through which to assess our roles in the classroom and in the academy. As stated in the keynote, the key to changing mindsets is disequilibrium. Disequilibirium relies upon new and unfamiliar experiences that cause us to abandon routine and encourage active thinking; if we – as sociologists – are committed to learning as a “social act”, we must be committed to creating opportunities for disequilibrium and to developing an “empowered, informed, and responsible learner.”

To learn more about the DDNRC, you can visit http://www.difficultdialoguesuaa.org/ or check out their Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/DifficultDialogues.org. Also see Indigenous Solutions to Intellectual Violence – Stop Talking and Listen.

Shantel Gabrieal Buggs is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Department of Sociology, studying race, gender, sexuality, and popular culture. Her dissertation will explore the online-dating experiences of mixed-race women in Central Texas. Follow her on Twitter at @Future_Dr_Buggs.

Brandon Andrew Robinson is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Department of Sociology. His research interests include sexualities, queer spatialities, and intersectionality. His dissertation will be exploring the lives of LGBTQ homeless youth.

Emeritus Professors John Higley and UVA President Teresa Sullivan celebrating 100 years of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. Video of President Sullivan’s speech

Emeritus Professors John Higley and UVA President Teresa Sullivan celebrating 100 years of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. Video of President Sullivan’s speech

The Sociology department at the University of Texas at Austin turned 100 this year, an event worthy of celebration. Many thanks to University of Virginia President, Dr. Teresa Sullivan (former Longhorn Vice Provost and proud Sociologist) for her talk on the future of Sociology and her help in launching our next 100 years. A video of our first 100 years can be found here.

Our social media savvy tweeters dominated at ASA and keep our blog lively with new posts weekly. This article from ASA answers the question: Why bother with social media at all?

Blogger Marc Smith’s Twitter Analysis Graph from the ASA annual conference.

Blogger Marc Smith’s Twitter Analysis Graph from the ASA annual conference.

Blogger Philip N. Cohen’s Family Inequality blog post on the twitter graph.

Why should I bother? (link to ASA article)

The shortest, simplest answer to the question “why should I bother?” is “You don’t have to.” Really, you don’t have to be on television if CNN calls. You don’t need a Twitter account. But, there are some reasons you might want to do these things.

Here are just a few.

Using social media can facilitate:

1. Establishing yourself as an expert

2. Conceptualizing and developing ideas

3. Developing a reputation for your thoughts, ideas and interactions

4. Building relationships

Social media analysis challenges stereotype of conservative state

By Amanda Jean Stevenson

The full text of the article is available at this link to the June 24th edition of The Houston Chronicle

One year ago this week, state Sen. Wendy Davis drew national attention with her filibuster of HB2, an omnibus abortion restriction bill that has since ushered in a 50 percent decline in the number of abortion clinics in our state. For 11 hours a year ago today, she stood on the floor of the Texas Senate in her pink running shoes as thousands of Texans rallied around her at the state Capitol and 180,000 people watched online. Her filibuster also sparked the wildly popular social media hashtag #StandWithWendy, instantly offering insight into a segment of the state that isn’t so red: Not all Texans agree that restricting abortion rights is a good idea.

Most discussion of Texas in the national media focuses on the state’s extremely conservative factions. But Texas is full of principled people across the political spectrum. Thousands of them marched on the state Capitol to oppose HB2. Before Davis filibustered, 700 people registered to testify in a “citizens filibuster” that lasted late into the night of June 20, and thousands filled Capitol buildings day after day dressed in orange T-shirts, the color chosen to symbolize the fight against HB2. After Davis’ filibuster, 19,000 filed comments against the bill and they continued to fill the Capitol for each hearing and vote. Throughout, they were joined by a digital chorus on Twitter that was hundreds of thousands strong.

I have analyzed the 1.66 million tweets that comprise the Twitter discussion associated with the bill. These tweets came from 399,000 users worldwide. Roughly 44 percent of the tweets were sent from Texans in support of abortion rights, and in all, about 115,500 Texans expressed their support for abortion rights as part of the Twitter discussion of the bill. These Texans are not all Austin liberals. They live throughout the state, in rural and urban areas. In fact, tweets in support of the filibuster were sent from 189 of Texas’ 254 counties, including the majority of rural counties and all urban ones. Only 1.8 percent of the Texas population lives in counties from which no identifiable tweets of support were sent.

Intellectual violence in the academe is a hot topic and was the subject of an animated Sociology brownbag last year. There was consensus about the problem, but no real solutions emerged. So, when I signed up for the Stop Talking – Indigenous Ways of Teaching and Learning workshop offered by the Humanities Institute, I was glad to discover valuable insights and techniques for creating civility in often heated academic discussions.

Co-presenters Ilarion (Larry) Merculief, the director of the Global Center for Indigenous Leadership and professor and Director of the University of Alaska at Anchorage’s difficult dialogues program Libby Roderick have co-authored and published two books. The first provided the foundation for our meeting and the second, Start Talking: A Handbook for Engaging Difficult Dialogues in Higher Education is a companion piece for instructors teaching courses that deal with contentious issues. Ilarion, an Alaskan native, began by describing his life as a child growing up in a traditional aleut village. His family were hunters and fishers, members of a small Unungan community living on St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea. From an early age, the children were taught to open their minds and their senses to the earth and sea and to listen. A typical greeting, translated as “The morning tastes good,” reflects their sense of well-being living in harmony with nature. Parents allowed children the freedom to roam and they were not chastised or punished for misdeeds, but taught communal values by elders and by their Aachaa, with whom they had a special spiritual bond. Time, attention and belonging were predicated on nature, on place, and on being one of the people who kept the balance of life by honoring and protecting the earth. People spent a lot less time talking and much more listening and communicating non-verbally. The foundation for respecting all living beings was given to Ilarion along with the challenge to communicate this balance of life, self and other to non-natives.

He began with a list of values that he felt most Alaska Native cultures have in common:

Clearly, a very civil agenda and one sorely lacking in most academic discourse. The foundation of respect comes from the knowledge that the community is completely interdependent and rooted in love of the earth. One of the first things workshop participants were asked to do was go outside for a 10 minute exercise in listening and opening our senses to the environment. We went to the turtle pond by the main building to enjoy the beautiful day.

This re-centering and re-energizing exercise was one suggested method for engaging the mind/body and including the heart in the conversations to follow. Giving participants a chance to reflect before answering questions and building in spaces for silence slows the pace and gives introverts more opportunities to be heard. Another useful technique employed in the workshop was to create listening pairs, setting aside five or six minutes at a time for each person to talk about what they were learning with the other actively listening. Research has shown that using wait time as a teaching strategy to facilitate think time produces better responses to questions. Even issues that are divisive and contentious can be discussed if we allow each person to have their own truth and we are willing to listen without formulating a response. There will be additional posts from this workshop,from the Stop Talking handbook and from the Start Talking engaging difficult dialogues handbook. The value of these lessons cannot be overestimated and I am grateful to Ilarion and to Libby for sharing their wisdom with their southern compadres.