Eric Borja on Jeremy Lin:

The focus of this post is the social phenomenon that is Linsanity in order to simply get people to think about politics, and race in currently trending sports topics.

For those of you who may not keep up with basketball or watch ESPN constantly, may not know what Linsanity is.

Linsanity is a term coined by ESPN correspondents referring to the phenomenon that is Jeremy Lin- a 6’3’’, Asian American point guard on the New York Knicks. In just two short weeks Jeremy Lin has become an overnight global sensation. He has turned around a historical franchise (the New York Knicks) and has brought them out of obscurity, transforming them into a globally relevant team. His jersey has become the number one selling jersey of the NBA, his rookie card is estimated to sell for $20,000 to $25,000, and he is now covered 24/7 on ESPN.

Oh, and not to mention he is the first American born NBA player of Taiwanese or Chinese descent.

But the truth of the matter is, there have been a number of ‘Cinderella’ stories similar to Lin’s, present and past, throughout football, basketball, baseball and hockey. Yet their stories did not spark a global phenomenon, so why Lin?

Could it be because ‘Lin’ is a marketers dream? Spawning nicknames such as ‘Linsane,’ ‘Linsanity,’ and ‘Linderalla’? Or maybe it’s because he has taken his new fame and glory with humility? Or maybe because two weeks prior to all of this, he was sleeping on fellow teammate, Landry Fields, couch because he was so unsure of his future?

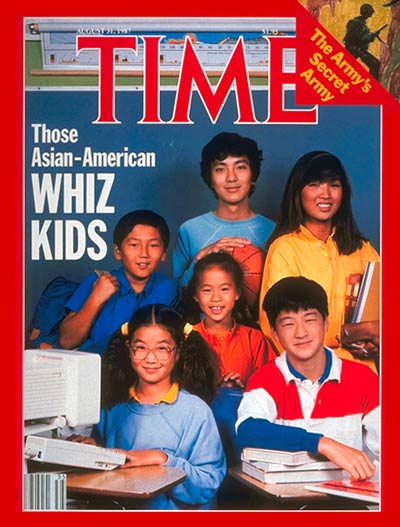

What really seems to be going on, is his race.

He is Asian American. He graduate from Harvard. He had a Xanga account with the username ChinkBalla88.

Jeremy Lin’s story is not just another story about an underdog, or a story about how hard work and perseverance leads to success, but is a story that brings to light sports, race, ethnic sensitivity in the media and politics.

A number of controversies surround Linsanity; one of the first being a tweet posted by Floyd Mayweather (a famous American boxer) on Febraury 13th, 2012. Mayweather wrote, “Jeremy Lin is a good player but all the hype is because he’s Asian. Black players do what he does every night and don’t get the same praise” (@FloydMayweather). This has sparked a number of public responses, ranging from UFC President Dana White calling Mayweather a racist, to prominent Knicks fan (and Director) Spike Lee replying on twitter, “I Hope You Watched Jeremy Hit The Gamewinning 3 Pointer With .005 Seconds Left.Our Guy Can BALL PLAIN AND SIMPLE.RECOGNIZE.”

Another, and most recent, controversy has been the uproar surrounding an article about Jeremy Lin titled “A Chink in the Armor,” which resulted in ESPN editor Anthony Federico’ termination. In a matter of two weeks Linsanity has brought race, ethnic sensitivity and politics to the forefront of the sports media.

The Huffington Post article, a segment on Jeremy Lin’s appeal in China, the segment aired on ESPN about ethnic sensitivity and the column responding to the article “A Chink in the Armor” can all be found at the end of this post. I strongly recommend you check them out.

I’ll end the post by just pointing to a couple things from the column responding to the article “A Chink in the Armor”.

The first thing I want to point out was the link embedded in the column to a 15 year old Jeremy Lin’s Xanga account. I point this out because it is such a great example of how technology has collapsed the space/time continuum. What I mean is that the photos were taken in a room (space) occupied by a 15-year-old Jeremy Lin (time), under the username ChinkBalla88.

A kid, who had no idea what was in store for him in the future, took some silly photos that are a reflection of what kids do. They play around with identities, and for this 15 year old Jeremy Lin, he was ChinkBall88.

But little did he know, that tho(e)se photos would/are (now) being conjured up 8 years later in an ESPN article about ethnic sensitivity in sports. Here we are, in an age where our past, present and future can be downloaded in an instant.

The final thing I want to point out is something the author of the column wrote referring to an Army Private by the name of Danny Chen. Danny Chen took his own life while on duty because a group of his superiors harassed him on a daily basis. They called him ‘gook,’ ‘chink’ and other racial slurs, threw rocks at him and just generally made his life a living hell. The author wrote, “Perhaps it’s a bit damning that four words about a basketball player sparked such outrage while a tragedy like the death of Private Danny Chen went largely unnoticed, but the fucked-up truth is that the story of Danny Chen might have received its proper respect had it come post-Linsanity.”

Linsanity could have made the death of an individual relevant, but instead, the death of Danny Chen went largely unnoticed in the pre-Linsanity world.

Also be sure to check out sociology faculty member Dr. Ben Carrington on the show the Stream. The segment is incredible and insightful and Dr. Ben Carrington does an incredible job.

Links:

Video of the debate about Ethnic sensitivity on First Take:

http://espn.go.com/blog/new-york/knicks/post/_/id/12515/stephen-a-and-skip-on-race-and-forgiveness

Video of Jeremy Lin’s appeal in China:

http://espn.go.com/blog/new-york/knicks/post/_/id/12635/abc-news-linsanity-in-china

Column in response to article titled “A Chink in the Armor”:

http://www.grantland.com/story/_/id/7601157/the-headline-tweet-unfair-significance-jeremy-lin

Huffington Post article about Floyd Mayweather’s tweet:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/02/13/floyd-mayweather-twitter-jeremy-lin-knicks-star_n_1274832.html

Dr. Ben Carrington on the Stream:

http://stream.aljazeera.com/story/whats-behind-violence-sports-matches-0022054

Texans proudly “remember the Alamo,” but few remember the importance of the Battle for the Lost Battalion. Arthur Sakamoto, professor of sociology and Population Research Center affiliate at The University of Texas at Austin, wants to change that.

Texans proudly “remember the Alamo,” but few remember the importance of the Battle for the Lost Battalion. Arthur Sakamoto, professor of sociology and Population Research Center affiliate at The University of Texas at Austin, wants to change that. Sakamoto hopes this scholarship will once again raise awareness and respect for the Japanese American men who faithfully, and voluntarily served their country in a time when their family and friends were rounded up and placed in internment camps despite their American citizenship-their only crime being their physical likeness and extended familial ties to the enemy.

Sakamoto hopes this scholarship will once again raise awareness and respect for the Japanese American men who faithfully, and voluntarily served their country in a time when their family and friends were rounded up and placed in internment camps despite their American citizenship-their only crime being their physical likeness and extended familial ties to the enemy.