That’s one Huge Tex. Oh, right, BIG Tex. Anyway, in honor of our fallen flammable friend, and as an opening salvo in our blog’s new section, Social Logical Austin, click this link to follow the exciting adventures of some Texan transplant UT graduate students making their way in a strange new world: The Texas State Fair

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Better Know A Sociologist: 10 Questions with Christine Williams

Here at the UT Sociology Blog, we strive to find new and interesting ways to expose the people and research in our department. To that end, we present to you “Better Know A Sociologist,” where we ask 10 general questions to one of our illustrious faculty members. Given that this is our inaugural post, we thought, “why not start at the top?” Thus we present to you 10 questions with Dr. Christine Williams, chair of the UT Sociology Department.

Here at the UT Sociology Blog, we strive to find new and interesting ways to expose the people and research in our department. To that end, we present to you “Better Know A Sociologist,” where we ask 10 general questions to one of our illustrious faculty members. Given that this is our inaugural post, we thought, “why not start at the top?” Thus we present to you 10 questions with Dr. Christine Williams, chair of the UT Sociology Department.

1. What first attracted you to sociology?

I don’t know how I first got interested in sociology. I’d always developed this narrative that I discovered sociology in college after going through different majors like political economy and art history. But then, somebody – I think my sister -pulled out my high school yearbook – I went to a pretty small high school in South America, so each senior had their own page and their own quote – and in my quote, I talk about wanting to be a sociologist! So I was 16 years old when I graduated from high school so obviously I knew what it was and I said I wanted to be one, so who knows? I don’t know where that came from in my 16 year old self, but I do remember actually making the switch to being a sociology major and I think it had a lot to do with the fact that it was the place where I learned about social justice and social inequality and that’s where feminism was located in the academy, so I think that that’s what drew me to the major. I’ve always been interested in class and gender.

2. What did you do your dissertation on?

My dissertation was a study of men in nursing and women in the Marine Corps. It was published as the book “Gender Differences at Work.” There’s this book by Rosabeth Moss Kanter that’s very famous called “Men and Women of the Corporation.” It’s a bit old, but people still talk about it. Kanter says in the book that it’s all about being a numerical minority, that is, the token phenomenon that results in basically labor force discrimination. I thought I would compare men’s and women’s experiences as tokens, but my original case study design was women in the Marine Corps and men in ballet because I had this title in my mind : “Men and Women of the Corps.” Like the Corps de Ballet and the Marine Corps, and I thought it would be this great hook because it was ultimately a critique of Kanter but I went to talk to an adviser in anthropology – who ended up not being one of my advisers – but he said that it was a stupid comparison and I got all, “Waaah, no!” I eventually figured out that he was right, but he was way too gruff in his manner and so I changed my case to nursing.

And so doing those studies, was that sort of what got you thinking towards doing the research that would eventually result in “Still A Man’s World”?

Yeah, after I had published “Gender Differences at Work,” one of my reviewers – it was actually Arlene Kaplan Daniels, who recently passed away. She mentored the whole generation of scholars that are my age. She was really really important and is missed – she gave it a very positive review and said that she was especially interested in the case of men because sociologists of gender have basically ignored men up until then and that the case of men in nursing was just fascinating and new and so that’s when I decided to expand my second book to look at more than one occupation that was female dominated.

3. Why did you decide to work here at the University of Texas?

Because they offered me a job! [laughs] Nobody picks where they work, this is where you end up. It was very funny because my first job was at the University of Oklahoma and that’s where I was an undergraduate. I was two years into being there and I was pretty miserable. I was the token qualitative person and the token theory person and it was just miserable, so I went back on the job market and applied everywhere. I almost didn’t apply here because I thought, “Oh UT, that’s going to be exactly the same as Oklahoma and I just want to get out of this part of the world.” But I came down here for my interview and I was just blown away. It was pretty and it had hills and people were really nice and excited about my work. I had just come from an environment where as an assistant professor I was constantly being criticized. Here everyone thought I was great and I thought they were great so it was a good match.

So when you got here, did you see this as a place you wanted to stay, or did you see this as just another part of your journey?

I had my career ups and downs here. I was pretty unhappy at one point because I thought they would count my two years [at OU] towards tenure and they didn’t – they would do such a thing now, but back then they had more stringent rules about time and rank – so they didn’t let me go up early and I was pretty unhappy about that and threatened to leave but never did. You know, I’ve been here for almost 25 years and I can’t – I often think about where I’d rather be other than here and I can’t think of any place. I can’t think of any place that would be as good as this. Of course I have this great lifestyle where I go away in the summer and get to live in the Bay area, so that kind of gives me the best of both worlds.

Definitely. Avoid the Texas summers if you can.

I know! But I still get to have the big ranch house and an easy bike commute and fantastic students and a great department.

4. What’s your overall experience of Austin then? What do you like about this place?

I like that it’s very relaxed and informal, although I understand that’s less so these days downtown. I just don’t go there. I think I, like a lot of people, live in a very small part of Austin. I basically live in a three mile radius of my home and I think it’s great. I don’t know what you’d want more than this. Of course, I spent a lot of my childhood traveling, so having a place that where I’m actually going to live for a long time is something attractive and very different for me.

5. If you could teach one sociological concept to the world, what would it be?

Mmm. Well it wouldn’t be the glass escalator, because I already did that and now I’m backtracking on that. There are flash cards with the glass escalator, it’s in hundreds of textbooks: kids all over the country are being given multiple choice questions on “what is the glass escalator?” So it’s happened.

So talk about that. It sounds like you’re a bit conflicted. How do you feel about having that sort of legacy or this concept that you created out in the world and you don’t really have as much ownership over how it’s being discussed and taught?

Well, it’s a good feeling. You know, I didn’t actually invent the term, [my partner] did. [laughs] I was sitting there working on the article because I had published two books already and my senior colleagues told me that if I wanted to get tenure at Texas I had to publish articles too. So I was working on this article that became the glass escalator article and I was looking at my analysis and saying “It’s like these guys keep on getting moved up even though they don’t even necessarily want to move up. It’s like they’re on some kind of elevator or something!” And he goes, “no, it’s an escalator, because they have to work to stay in place.” And I said, “That’s it!” I remember it very vividly, that conversation. So it’s very gratifying to know that – and I think it’s a good concept because people know intuitively what it means because it has a counterpart with the glass ceiling, and I do think that’s partially the secret to success is to come up with some catchy term. I mean, Arlie Hochschild really refined that with “the second shift” and “the time bind.” She keeps coming up with these great – like “the global care chain,” that’s another one.

Or emotion work.

Emotion work! I mean, all of these ideas, people can intuitively grasp what they’re about and it’s very cool. No, I’m backing away from it not because I think I was wrong but because I think that the world of work has changed so that there are many, many careers today that have no career ladder. You can’t have a glass escalator unless there is the opportunity for promotion. I think it’s a concept that’s grounded in an earlier form of work and we need new concepts.

It’s almost like a treadmill now.

Yeah, or a trap door is another one that we’re thinking about. So we’re thinking about the limitations of the glass escalator concept and we’ve got an article forthcoming in Gender & Society next year.

6. What’s the most rewarding part of your job?

This. Graduate students. Talking about ideas.

Why is that?

What other field do you get to be around a bunch of brilliant young people who are basically creatively thinking about society? There’s nothing else that comes close to it.

7. Who is one person in the department besides yourself that you think is doing really interesting work and what is it?

Well, it’s really funny, most of us don’t know what each other does, and I do because I’m chair. The thing that just boggles my mind is how much amazing work is being done here. When you asked that question, I was like, “Holy cow, what am I going to say?” I mean, is it going to be Sharmila’s [Rudrappa] work on surrogacy, Deborah’s [Umberson] work on gay marriage, Ron’s [Angel] work on post Katrina… It’s just endless. My colleagues over in the Population Research Center are also doing really interesting and innovative work, so I couldn’t pick. I mean, Michael Young’s work on immigrant rights, Ari’s [Adut] work on the French Revolution – I get to read all of this stuff – Gloria’s [Gonzalez-Lopez] work on incest, it just goes on and on.

It’s an embarrassment of riches.

It is, and it helps us to understand why we’re so highly ranked but it also has to do with our ability to interact with and mentor excellent students. Just having that intellectual stimulation – we didn’t always used to have that here and I think it’s something that we’ve cultivated and grown. Virtually everyone in the department is doing interesting work now. I mean, Joe Potter’s work on contraceptive health and health policy, it’s just, it’s first-rate and it’s so interesting.

8. What are your current research interests? What are you looking at these days?

Well, the short answer is women geoscientists in the oil and gas industry, but I think my heart lies in understanding work transformation and deindustrialization. What’s really interesting to me is how a lot of policies meant to promote gender equality have been designed with professional women in mind and I think that policies that aid them may actually diminish poor women. So I think there’s a real need to understand how social policies have a class basis to them. Especially poor women, but also men, because a lot of the time they’ll say, “OK, there’s a gender wage gap”. Yeah, she’s earning $7.50/hr, he’s earning $7.80/hr, so both of them are struggling, OK? It’s like it’s almost the wrong issue. And the focus sometimes on gender disparities at the bottom of the wage scale I think prevents worker solidarity. This is the stuff that I’ve been teaching to you since I first met you, sort of combining the gender and sexuality with the labor markets.

Exactly. And sort of the effect of neoliberalism towards putting men and women in a race to the bottom in terms of wages.

Right. And we can still detect gender disparities but are they the issue when people are not earning living wage? No, they’re not. On the high end, it’s “OK we’re going to get women into the CEO suite,” but it’s going be a pyrrhic victory if they’re just going to continue to impose these neoliberal reforms and slash any kind of benefits and wages. No thank you! That’s not my feminist movement.

9. What’s one book you’ve read in the past year that you’ve really enjoyed and why?

Well, the book I’m reading now is just amazing. It’s Sinikka Elliott’s book – which was her dissertation here at UT – and I’ve assigned it to my undergraduates. There’s just so many wonderful feelings involved in seeing this work from its inception. It’s called “Not My Kid,” and it’s about what parents believe about the sex lives of their teenagers. They all think that their kids are good and innocent and other people’s kids are hormone driven sex maniacs and this belief, she argues, reproduces social inequality but it also prevents teenagers from getting any kind of thoughtful, useful information about sexuality and relationships.

10. What do you enjoy doing in your free time?

I enjoy bike riding and reading. Especially novels. I also enjoying swimming and yoga and drinking beer.

Research Q & A – A Dynamic Duo of Crime Fighting: APD and UT Sociology

Recently, the Austin Police Department was awarded funding from The Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Program, a program begun by the Department of Justice to help facilitate place-based, community oriented strategies to address neighborhood crime. As part of their proposal, APD has involved the UT Department of Sociology in the planning and evaluation steps of this multi-year project. We sent our intrepid blog editor to interview Dr. David Kirk, Associate Professor and lead researcher on the project, to find out more.

Why did APD decide to involve the UT sociology department?

Well, they were looking for research partners that had some experience with community crime prevention and neighborhood development and I had contacts at APD who were aware of my research. A core piece of my research agenda is understanding the relationship between crime and community conditions. APD knew I was familiar with the White House Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative through some work I have done with the National Institute of Justice. So I am familiar with what the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Justice Assistance want to accomplish through this grant program. Additionally, given my research background, I can help them both design a crime prevention program and evaluate it after implementation.

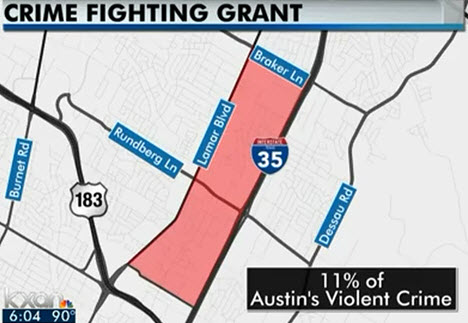

This project is specifically focusing on the area north of 183 around Rundberg Lane. Why was this area targeted?

The nature of the grant program is to identify a neighborhood in a given urban environment that accounts for a disproportionate amount of crime in a given city. So when APD and I developed the grant proposal, we looked at neighborhoods where crime concentrates. Here in Austin, the crime rate is fairly low compared to the crime rate in other urban areas, but it’s very concentrated and the Rundberg area is one of the extreme pockets of crime in the city. So the decision was kind of made for us based upon the distribution of crime.

Are place-based crime strategies effective?

Definitely! The particular strategy that we’ll end up applying in the Rundberg area won’t apply everywhere of course, but certainly place-based strategies do work and not just in areas where there are high rates of crime.

One of the goals of this project is to not just reduce crime rates, but to “empower residents” of the neighborhood. Why shouldn’t these funds just go directly into enforcement and surveillance?

Because if you just spend the money on enforcement and surveillance it’s not developing community capacity like it needs to. So the idea is that after a three year period – a year of planning, a year of implementation, and a year of evaluation – the project funds will go away but the effort will be self-sustaining because the collective capacity of the neighborhood has been built up. It’s not just about reducing crime; it’s also about building collective efficacy in the community so that you have residents and the police and the DA and community organizations all working together. So we want to establish social network ties, establish working relationships; therefore even when the money goes away, they’ve got an institutional framework for continuing to fight crime.

What does “empowering residents” mean? What might it look like?

What does “empowering residents” mean? What might it look like?

It can be as simple as encouraging residents to report crimes or to start neighborhood watch programs. Yet a specific motivation for this grant program is to directly involve the community in the planning process. That empowers residents. They will work with city leaders, community organizations, and UT to analyze the problems in the community and figure out what solutions make sense. Ultimately, if we just rely upon the police to control crime then we’re not capitalizing on the fact that there are all these other entities that could help out.

So just to be clear, we’re not talking about empowering residents to fight crime themselves, we’re talking about empowering them to address the causes of crime and to reduce the crime rate in that fashion?

Well, I’m definitely not talking about vigilante justice where you arm residents and have them go out and fight crime! [laughs] But I AM talking about empowering residents to work with the police. For example, one characteristic of a lot of communities that have high levels of crime and socioeconomic disadvantage is that relationships with police are characterized by a lot of animosity and distrust. But if you bring the police and the residents in a collective process that’s designed to address community problems and they start talking, they realize it’s possible to reach common goals by working together. So part of the project is to work at reducing this distrust between the community and the police. And that goes a long way towards lowering crime.

That makes sense. What about the community of social services? How will they be involved in this?

They will be directly involved. One of the big issues in the Rundberg area – and this applies to a lot of urban neighborhoods – is concentrated prisoner reentry. You’ve got a lot of folks coming out of prison going back to neighborhoods and often times there’s not a great understanding of what kind of resources are available to help these folks reintegrate back into society and furthermore, a lot of the time the community itself may not even understand their needs. So we want to have the community communicating to individuals what kinds of resources are available. For example, “here’s an organization that provides job training for free,” or “here’s a treatment facility that actually has bed spaces,” or “I heard about this company that will hire ex-offenders,” that type of thing. So that’s one way to help facilitate the reintegration process for ex-prisoners. The theoretical idea is that if you have a structure of social service providers and non-profit organizations, these are important entities that can contribute to the control of crime.

Are projects like this common? A lot of times professors and academics are seen as “hands off” intellectuals, sitting alone in an Ivory Tower somewhere. Why is it important to be involved in on the ground projects such as this?

Well, different academics have different research trajectories. I have not done a lot of applied work. But this project is an opportunity to help a community and that’s certainly the most important thing to me. It’s interesting from a research aspect as well. There are research questions we can ask by trying to revitalize a neighborhood. I mean, the whole question of “can we get the police and the community and these other entities to work together effectively,” that’s an interesting question in its own right. It’s also important to research what it takes to foster better relationships between the police and the community. Personally, I definitely think it’s useful to apply what I’ve learned sitting here in my office running statistical models in the service of trying to help a community.

Anything else you feel is important that I may have missed?

I would just emphasize the nature of the three year project. It’s a well developed grant program that the Department of Justice has put together and so they’re providing the city and police and UT a year of funding to analyze the problem intensively. And then the idea is that after people have analyzed what’s going on in the area – and here we’re not just talking about crime, we’re also talking about housing, employment prospects, etc. – we’ll collectively come together and identify what types of intervention would make sense in the neighborhood. Then there’s the implementation phase and that has its own challenges. And then after that UT will come in and evaluate it and see whether or not it was a success. So it’s a big, three year effort. It’s going to present me with some different research challenges, but I’m excited. The Chief of Police predicted that there would be real change in the neighborhood. There are a lot of people interested in helping out the community and the community itself is interested as well, so I’m optimistic that we can make his prediction come true.

Cover Image provided courtesy of KXAN

Our new home beginning Spring 2013 – a work in progress

Will we change the banner of our blog when we move into the new building next semester? Perhaps, but even more interesting will be the cultural changes we experience as we move into this monumental, very modern space. Many of us have become fond of Burdine Hall (I am among the sentimental) but as you can see below, even in this state of becoming, our new space is really impressive.

“Changing the Reputation of Rundberg”: APD Hires Sociology Professor in Community Reclamation Project

The Austin Police Department received a federal grant of $1 million to study and improve Rundberg Lane, an area that makes up 11 percent of all violent crimes in Austin. The money will be used to increase police presence and to hire The University of Texas at Austin Sociology Professor David Kirk for one year to research and plan a long-term solution. APD is one of seven police departments across the country to receive the grant as part of The Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation Program.

Marx Attacks!: A Lesson in Collective Effervescence

Here at the UT Department of Sociology, we believe in one simple truth: the history of the world is the history of football (or soccer, if you’d like to be American about it) struggle. There is a dialectic between the talented and the talentless, and out of that primordial stew, somewhere, somehow, the UT Sociology Intramural Football team arose. Now in its fourth year, the team stands as a shining example that graduate students do indeed recognize a world that exists outside our piles of books and revise-and-resubmit articles. Under the name Marx Attacks! – for we are both economic materialists and a green, space faring race from Mars that has come to destroy the planet in a very 1950s pulp fiction way – we continue to fight the good fight, confident that one day the people will rise up behind us and declare to the world “Hey, these guys are pretty good for being grad students! Maybe we should let them score more.”

The team is always looking for new players of any skill level to join. We play outdoors at the IM fields for four weeks in the fall, and indoors at the Rec Sports Gym on campus for four weeks in the spring. We try and practice once a week, and often head to the Flying Saucer afterward. During practices, we sometimes scrimmage against other departments and programs – mainly history and LLILAS.

Professors Javier Auyero, Ben Carrington, Art Sakamoto, and Alex Weinreb (together known as the “athletic vanguard”) have graced us with their presence on occasion in the past; professors, students, and enthusiastic spectators are welcome. The more, the merrier!

Email Eric Borja if you’d like to join us: busymrgribble@gmail.com

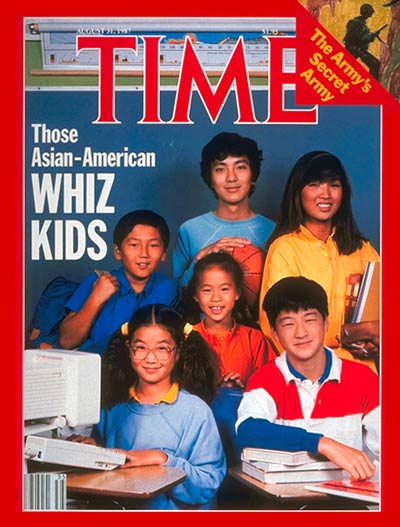

Minority Reports: Asian Americans in Class and at Work

ASA

Regular Session on Asians and Asian Americans: Economic and Educational Processes. ‘Discrimination and Psychological Distress among Asian Americans: Exploring the Moderating Effect of Education’ (Wei Zhang, University of Hawaii; PhD, UT-Austin, 2008); ‘Are Asian American Women Advantaged? Labor Market Performances of College Educated Female Workers’ (ChangHwan Kim, University of Kansas; PhD, UT-Austin, 2006).

Zhang and Kim, respectively, revealed surprising findings about correlations between education level and psychological distress from discrimination, and between nationality and workplace inequality, among Asians and Asian Americans.

Zhang discovered that Asian Americans with higher levels of education experience more psychological distress from racial discrimination than those with lower levels of education. In addition, Asian Americans who received their education outside the US experience more distress from discrimination than those who received their education Stateside. One possible explanation is the disparity between others’ perception of the individual and the individual’s self-perception or expectation is exacerbated when the individual’s education level contributes negatively to his or her cognitive stress.

Studying Asian and Asian American women in the workplace, Kim found that Asian American women do not hold an advantage over Asian-born women working Stateside in terms of employment, compensation and professional upward mobility, and both fare worse than white women in these aspects.

These results show the real discriminations and inequalities that Asians and Asian Americans face are often overlooked in favor of a model-minority stereotype that emphasizes only the positivity of educational attainment and cultural assimilation while ignoring their stress effects in context with other psychological and economic factors, and that, perhaps, it is still a ways to a racial and socioeconomic utopia realized.

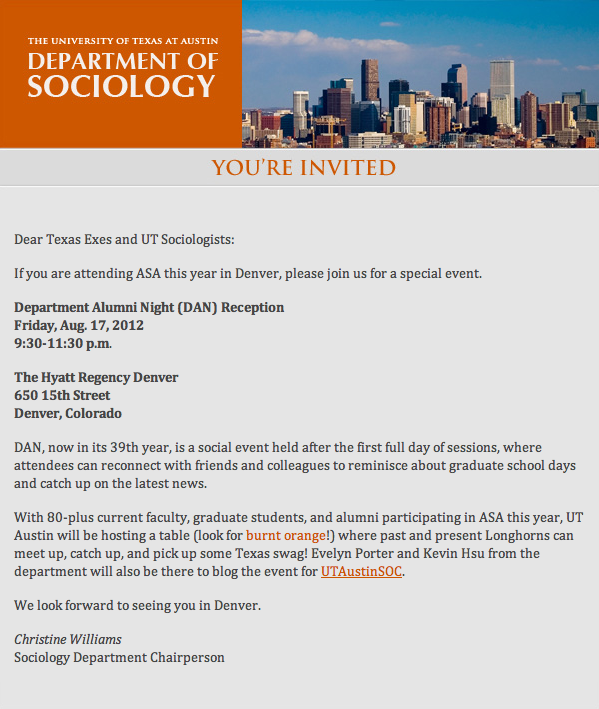

Join us at alumni night in Denver

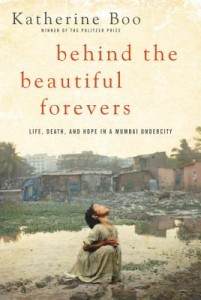

“Lives at the Urban Margins”

Katherine Jensen and Javier Auyero review Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity (2012), Sebastián Hacher’s Sangre salada (2011), and Josefina Licitra’s Los Otros: una historia del conurbano bonaerense (2011):

Katherine Jensen and Javier Auyero review Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity (2012), Sebastián Hacher’s Sangre salada (2011), and Josefina Licitra’s Los Otros: una historia del conurbano bonaerense (2011):

Excerpt

“Every great city,” wrote Friedrich Engels, in The Condition of the Working Class in England, “has one or more slums, where the working-class is crowded together. True, poverty often dwells in hidden alleys close to the palaces of the rich; but, in general, a separate territory has been assigned to it, where, removed from the sight of the happier classes, it may struggle along as it can … The streets are generally unpaved, rough, dirty, filled with vegetable and animal refuse, without sewers or gutters, but supplied with foul, stagnant pools instead.” More than a century and a half later, the subproletariat still inhabits treacherous, dreadful grounds in today’s megacities. With close to a third of the world’s population living in informal settlements, many of them mired in misery and violence, the need to understand and explain their lives is as imperative as it was when Engels first wrote these words. Three recent books here under consideration take up this task in two very distinct cities, Buenos Aires and Mumbai, dissecting the material and symbolic dimensions of life on “the other side.” These vivid portraits convey the external and internal forces that shape and sustain the slum’s challenges, its struggles, its relentlessness, and its cruelty.

A dexterous combination of detailed, in-depth reporting and crisp, dynamic writing heeds the calls that urban ethnographers have been making for the past three decades: calls for capturing the viewpoint of those living under oppressive conditions, calls for thick descriptions of their lives and circumstances, calls for narrative writing that appeals to larger publics and politics. These are not only engaging books to read, however. While teaching about the trials and tribulations of residents of stigmatized territories, these three texts provide elements to outline a much-needed political sociology of urban marginality. They describe many of the ways in which the state is deeply implicated in the fate of what sociologist Loïc Wacquant calls “territories of urban relegation.”1

Privileging the showing more than the telling, authors Boo, Hacher, and Licitra not only allow readers to make the connections between structural forces (such as informalization of the economy or deproletarianization or changing labor markets dynamics) and the lives, behaviors, and beliefs of those at the bottom of the sociosymbolic order. They also demonstrate how the state regulates poor people’s lives sometimes overtly (in the form of police repression, forced evictions), other times covertly (through extortion and intimidation) reproducing much of the precariousness, vulnerability, and violence that define them, and ultimately keeps the dispossessed in their (to a large extent) invisible place.

Privileging the showing more than the telling, authors Boo, Hacher, and Licitra not only allow readers to make the connections between structural forces (such as informalization of the economy or deproletarianization or changing labor markets dynamics) and the lives, behaviors, and beliefs of those at the bottom of the sociosymbolic order. They also demonstrate how the state regulates poor people’s lives sometimes overtly (in the form of police repression, forced evictions), other times covertly (through extortion and intimidation) reproducing much of the precariousness, vulnerability, and violence that define them, and ultimately keeps the dispossessed in their (to a large extent) invisible place.

Click here for the full review at Public Books.

ASA 2012: Receptions

A number of ASA Sections and Units will be holding individual or joint receptions this year. Here is a sampling if you are planning to attend (search for more here):

(On-site at the Hyatt Regency Denver unless noted otherwise–locations TBA)

Joint Reception: Section on Sex and Gender; Section on Sociology of Sexualities; Section on Race, Class and Gender (offsite)

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Joint Reception: Section on Global and Transnational Sociology; Section on Comparative and Historical Sociology

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Section on Marxist Sociology Reception

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Section on Sociology of Culture Reception

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Reception for Scholars with International Research & Teaching Interests

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 6:30pm – 7:30pm

Student Reception

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 6:30pm – 7:30pm

Section on Asia and Asian America Reception (offsite)

Time: Fri, Aug 17 – 7:00pm – 9:00pm

Section on Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis Reception (off-site)

Time: Sat, Aug 18 – 7:30pm – 9:00pm

Section on Latino/a Sociology Reception (off-site)

Time: Sat, Aug 18 – 7:30pm – 9:00pm

Joint Reception: Section on Collective Behavior and Social Movements; Section on Political Sociology; Section on Human Rights

Time: Sun, Aug 19 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Joint Reception: Theory Section and Section on History of Sociology

Time: Sun, Aug 19 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Joint Reception: Section on the Sociology of the Family; Section on Sociology of Population (off-site)

Time: Sun, Aug 19 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Section on Animals and Society Reception

Time: Sun, Aug 19 – 6:30pm – 8:30pm

Joint Reception: Section on Science, Knowledge and Technology; Section on Body and Embodiment (offsite)

Time: Sun, Aug 19 – 6:30pm – 8:00pm

Utopia Reel: An Evening of Dancing and Music-Making

Time: Sun, Aug 19 – 7:30pm – 11:55pm

We hope to see you at some of these events!