The Center for Women’s and Gender Studies will be hosting its 23rd Annual Graduate Student Conference on March 23rd, 2016.

Several members of the Sociology Graduate Community will be presenting! See their papers and abstracts below and go support your fellow graduate students:

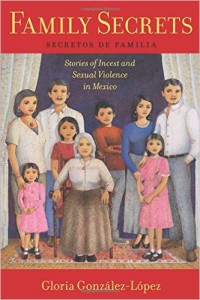

Anna Banchik: Photography and the Spectacle of Race

In 2008, families in Libya began protesting in order to seek information about male relatives who had been forcibly disappeared, and subsequently killed, by the government. Despite the prevalence of forced disappearance cross-nationally, these mobilizations in response have seldom been studied from sociological point of view. This paper seeks to understand mobilizations in response to forced disappearance from a sociological perspective that considers the role played by mourning and trauma in social movement organizations. Social movement scholars have recently considered the significance of emotions in collective organizing but have focused primarily on dynamics related to pride, shame, anger, and indignation, among other emotions. While some scholars have addressed grief, there has not been a sustained focus on issues of mourning and trauma in social movements. I focus on the case of Libyan mobilizations around disappearance to argue that grievances over the disappeared body are characterized by expressions of mourning and the experience of collective trauma, which serves to sustain their movement. Families engage in protest tactics that both commemorate and reframe the lives of their loved ones and express grief for their loss. This study contributes to our understandings of how the missing body and protracted mourning have the potential to motivate and sustain social movements.

Shantel Buggs & Ryessia Jones: Disciplining Olivia Pope: Race, Gender, Family, and the Power of Whiteness

While much of the discussion regarding race and gender in Scandal is reserved for its portrayal of interracial relationships – specifically the sexual relationship triangle between Olivia Pope, President Fitzgerald Grant, and Jake Ballard – the majority of Olivia’s interactions are informed by, and enacted through, whiteness. Olivia has relationships with White men, wears the “white hat,” associates mostly with White colleagues, and consistently uses her resources to save the careers and lives of White political figures. This essay explores the ways in which whiteness emerges in the television show, Scandal, a scripted show created by Shonda Rhimes and starring Kerry Washington, both Black women. More specifically, this chapter reveals how whiteness is utilized as a mechanism for policing and disciplining the Black female body, specifically through an analysis of Olivia’s relationships with Fitz, Jake, Mellie Grant, Abby Whelan, and Olivia’s father, Rowan (Eli) Pope. As Frankenberg (1993) argues, “whiteness” is the means of producing and reproducing dominance, normativity, and privilege (236); thus, White people have a “possessive investment” in its success (Lipsitz 2007). Because whiteness is a social construction, it informs not only how we understand constructions like gender and race in the “real” world, but it our fictional worlds as well.

Prisca Gayles: Re(membering) the Past and Recovering the Present: Black Activist Responses to Controlling Images and Stereotypes of Black Women in Argentina

This paper examines Black activism in Buenos Aires from a Transnational Black Feminist and Subaltern perspective. The present project is necessary because Afro-Argentine women have either been erased from or misrepresented in Argentine historiography and are currently situated in a system that threatens to reproduce this injury. I begin with a review of the ways hegemonic historiography in Argentina has contributed to the present day myth of non-existence of Afro-Argentines. I then examine the trivialization of actions, assumptions, and practices in Buenos Aires that violate the black female body by assigning her a static and/or stigmatized role. I do this with an analysis of the vendedora de empanadas (the empanada seller), the most reproduced image of the Afro-Argentine woman of the nation’s past, who today is represented with blackface practices. I ask in what ways this controlling image is related to the injurious experiences of black women in Argentina today. Although I locate the simultaneous invisibilility and hypervisibilty in the figure of the vendedora de empanadas I do so as an example, only one in a myriad of ways in which this is true for black women in Buenos Aires. Finally I draw on Black activist responses to contest the relegated role of black women paying particular attention to “recovery work” in the visual field and the experiential knowledge of Black female activists. The intent of this paper is to argue that subaltern analyses are incomplete if they only write about subjugated groups. The gaps that subaltern projects seek to fill are enriched when they not only interpret the silences but also draw upon the experiential knowledge and transgressive practices of the groups they seek to represent. Thus, a Transnational Black Feminist approach to understanding the work of black female activists in Buenos Aires must necessarily be coupled with the subaltern approach.

Emily Paine: “Not…dead lesbians”: women’s experiences of sex in the midlife across same-sex and different-sex couple

I examine the experiences of women navigating sex amidst midlife transitions within same-sex and different sex long term couples. Data from in-depth interviews with women in 18 same-sex and 18 different-sex couples were analyzed to reveal how transitions related to caregiving, health and aging work to change women’s intra- and interpersonal experiences of sex and sexuality. I extend theories of gender and sexual scripts to examine how women framed and made sense of their changing sex lives in light of larger cultural schemas of gender and sexuality. For example, lesbian women negotiated their discordance from heterosexual scripts by framing their changing sex lives as either similar to those of heterosexual long term couples or too different to be understood through such scripts. Whereas straight women cited their alignment with the script of sexless long term heterosexual marriages, lesbian women negotiated stigmatized heterosexist scripts of lesbian asexuality. I introduce the term of lesbian “bed work” to describe the sense of responsibility and work undertaken to keep up sexual relationships discussed by lesbian women.

Samantha Simon: Male Strip Clubs as Revolutionary Sexual Spaces

In this paper, I argue that male strip clubs offer women an opportunity to destabilize normative forms of heterosexuality by actively and publicly desiring sex and that some of this transgressive behavior can become sexually violent. The existence and popularity of male strip clubs and bachelorette parties denaturalizes women as asexual by demonstrating that women actively desire sexual experiences. Though scholars disagree on whether these spaces either reinforce or disrupt gender norms, I argue that the mere existence of these spaces and their acknowledgement of female sexuality destabilize normative expectations of gender and sexuality. Some of women’s transgressive behaviors in male strip clubs could be described as violent. Interestingly, male dancers and the researchers who study these spaces do not describe them as such. These researchers may inadvertently be reinforcing conceptions of women as non-threatening and passive by describing patrons as “wild” and not “violent.” I argue that social discomfort with these transgressions is corrected for in the description of these events as not violent. Though I certainly do not condone this kind of behavior, I do argue that if we are able to acknowledge the existence of violent women and vulnerable men, we can contribute to the disruption of gendered norms of sexuality that lead to violence against women.

Maro Youssef: The Algerian state’s creation of terrorism and the “Islamist ghost”

The Algerian civil war, which lasted from 1991 to 2002, consisted of infighting among various Islamist militant groups that also were also engaged in warfare with the Algerian state. There were between 200,000- 300,000 deaths and at least 10,000 disappearances (7,000 of which the state later recognized). Following the civil war, the state created the “Islamist ghost” as Algerians demanded answers about the disappearance, abduction, torture, and death of at least ten per cent of the population during the war. The state constructed narratives of haunting and trauma using the “Islamist ghost” in order to create a docile population that would later re-elect the same president four times since the war.

Amina Zarrugh: “This vigil of ours is a vigil of truth”: The Role of Mourning and Trauma in Social Movements

In 2008, families in Libya began protesting in order to seek information about male relatives who had been forcibly disappeared, and subsequently killed, by the government. Despite the prevalence of forced disappearance cross-nationally, these mobilizations in response have seldom been studied from sociological point of view. This paper seeks to understand mobilizations in response to forced disappearance from a sociological perspective that considers the role played by mourning and trauma in social movement organizations. Social movement scholars have recently considered the significance of emotions in collective organizing but have focused primarily on dynamics related to pride, shame, anger, and indignation, among other emotions. While some scholars have addressed grief, there has not been a sustained focus on issues of mourning and trauma in social movements. I focus on the case of Libyan mobilizations around disappearance to argue that grievances over the disappeared body are characterized by expressions of mourning and the experience of collective trauma, which serves to sustain their movement. Families engage in protest tactics that both commemorate and reframe the lives of their loved ones and express grief for their loss. This study contributes to our understandings of how the missing body and protracted mourning have the potential to motivate and sustain social movements.